If you’re interested in Satanism, how Satanism developed, the Left-Hand Path and esoteric Satanism, and how the figure of Lucifer got reinterpreted more positively? Stay tuned because you’re just about to find out.

Hello everyone. Angela Puca, and welcome back to my Symposium. I’m a PhD and a University Lecturer and this is your online resource for the academic study of Magick, Esotericism, Shamanism, Paganism, Satanism, et al, and all occult.

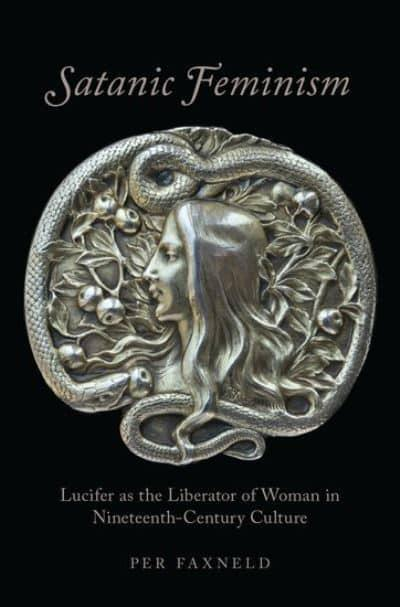

Today, I have a very special guest here. We are about to start the ESSWE Conference, the Conference of the European Society for the Study of Western Esotericism, at University College Cork in Ireland. My special guest is Dr Per Faxneld, Associate Professor in the Study of Religions at Södertörn University in Stockholm. He specializes in Satanism, the figure of the Devil, and also feminist outlooks on Satanism. You’re the author of “Satanic Feminism?”

Dr Per Faxneld PF: Yes.

AP: So yeah, that’s a big text. I will put his books on screen and also look in the info box because you will see the references and the links to his publications. So today we will be talking about a very, I don’t know, difficult subject it’s not really difficult but it’s more…

PF: Contested, shall we say.

AP: Contested, yes. I was trying to find a polite way of saying that. It’s a challenging topic to address because you know, there are so many, you know, even feelings on the part of people when it comes to Satanism, the figure of Satan, the figure of the Devil. But here we are. You know all about the academic study of this topic. So the first thing that I’d like to ask you is, what is Satanism? And when did it start?

PF: That’s a pretty, pretty big and broad question, of course.

AP: Yeah, so that the audience can have an overview.

PF: Sure, there are, of course, multiple academic attempts to define what is Satanism. But the definition that I tend to operate with is that Satanism is the, shall we say, reverence or adoration or positive reinterpretation of the figure of the Devil or Satan or Lucifer. The figure, of course, has many names formulated as a more or less coherent system of thought. So that’s a pretty basic definition for you. And, of course, there’s a lot that could be subsumed under this heading. And some groups might not be too keen, themselves, on being labelled satanic, which could also fit with this definition. So, we have to bear in mind that this is what we would call an etic definition instead of an emic one. So, it’s not necessarily the insider definition but rather a scholarly construct that we, as scholars, work with to delimit a phenomenon that we want to study.

Now, in my book “Satanic Feminism”, I further divide Satanism into two categories; where one is Satanism in the strict sense, which would be a system of thought primarily focusing on a positive reinterpretation of Satan. The second one would be Satanism in a broader sense, where the positive interpretation is just employed strategically as part of a much larger system that may encompass other Gods or entities and where Satan is not the primary one. Or it could be part of a political strategy, for example, and that was the first part of your question.

AP: Yeah.

And the second one is when did Satanism start? And again, that depends on if we’re talking about Satanism in the strict sense, like a complete system of thought focusing on this positive interpretation of Satan – that is, in fact, a lot later than you might think. But the more broad version of Satanism has its beginnings in the late 18th century with romantic poets. Poets who were typically political radicals and who were enthusiastic readers of John Milton’s epic “Paradise Lost.” And of course in “Paradise Lost,” John Milton gives a portrayal of Lucifer which, at the outset, comes across as quite heroic. Later, it’s revealed that his motives are based and he is fairly unpleasant and cowardly. But in the early parts of “Paradise Lost,” there’s this, sort of, seeming lauding, almost, of the figure Lucifer. Reading Milton as being positive towards the Devil was something that people had been doing for quite a while, actually, in the immediate time when it was written. Milton himself was the private secretary of Oliver Cromwell the revolutionary, against the crown in England. So people understood, quite early on, “Paradise Lost” as an allegory of the English Civil War where God would be the monarch and Lucifer would be Cromwell, the revolutionary.

This is why certain readers understood it as Milton praising the revolutionary because of his revolutionary background and this tradition that the romantics picked up on. But they focused specifically on the figure of Lucifer and started producing texts of their own where they reworked this character into a sort of icon of revolution. This became an established theme in literature and spread all across Europe and subsequently was picked up by socialists of various stripes all across the continent. And at this time, of course, it’s just Satanism in the broad sense, right? So it’s not Satanism as a whole system of thought just focusing specifically on Satan; it’s just part of a reservoir of sort of subversive symbols being employed.

AP: It’s a cultural wave.

It’s a cultural wave, absolutely, and of course, it’s very much tied up with the early history of secularism and secularisation. So these figures were often keen on removing the church’s influence and creating these counter-myths where they reinterpreted the Devil as a positive figure. Romantic authors, like Shelley, actively sought to destabilize the mythology of Christianity, which he felt was one of the pillars supporting the present order that he wanted to tear down right.

So that’s the sort of early roots of Satanism. But at this point, no one in an esoteric context was saying anything particularly positive about Satan. That’s a much later development, almost 100 years later. We find the first sort of tendencies in that direction in some of the writings of Èliphas Lévi, where he identifies this quite complicated concept in his cosmology, called the Astral Light. He identifies that with, well, with a lot of things; with the Holy Spirit but also with Lucifer, and there’s a like a tiny opening there in the direction of an esoteric Satanism. Of course, Èliphas Lévi considered himself a Christian, and his Luciferian sympathies are embedded within a generally Christian framework. But later on, other esoteric writers would pick up on this notion and turn it into something more fully fledged.

One of those, or the key figure in this context, was Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, one of the founders of the Theosophical Society and its first major ideologue. In Blavatsky’s, perhaps, most famous work, “The Sacred Doctrine,” from 1888, there are several passages where she makes a radical reinterpretation of the figure of the Devil, and what’s interesting here is that she uses the name Satan, Lucifer and the Devil interchangeably. So, it’s the same figure here in these passages. And what she presents is a drastic reinterpretation of the fall of man. So, the Garden of Eden events include eating the forbidden fruit. This is also interesting because this was such a key passage in the discourse of Christianity that sought to keep women in their place; of course, you know the story of eating the forbidden fruit and how Eve was the first to accept the forbidden fruit from the Devil or the serpent, actually, in the biblical narrative, which was later identified in Christian theology as the Devil. And because of this Eve was seen as weaker and more susceptible to the guiles of the Devil than her male counterpart. But with Blavatsky, this narrative is turned on its head. So the punishments meted out to Eve would no longer be fair punishments, for example, that she would give birth to children in great pain and things like that. This had been used politically by, for example, medical doctors arguing for not administering pain relief to women giving birth because this was supposed to be a punishment of God for Eve’s transgression – quite horrible. This was also used in the rhetoric of Witch-hunters and inquisitors, like the authors of the infamous Malleus Maleficarum, who also argued that women were particularly susceptible to the satanic. So this had had drastic consequences in European history, of course. Now Blavatsky then she turns the story in its head she says that Satan is not our enemy; Satan is the bringer of Gnosis, the serpent gives us a fantastic gift – setting our cosmic evolution in motion, and he has a bringer of esoteric wisdom.

So that’s a completely different story, and of course, this also re-frames Eve’s role in this drama. And quite a few early theosophical women picked up on this and saw the implications of what Blavatsky was doing here. They used this in their attacks on patriarchal Christianity, using this counter myth that Blavatsky came up with. But in terms of the History of Esotericism, what Blavatsky did here was that she established a tradition of esoteric Satanism. Now, I would never call Madame Blavatsky a Satanist because she’s not in a strict sense. If you look at her writings, if there’s a figure that she repeatedly returns to and praises – it would be the Buddha. So it’s not Satan, and in that sense, of course, it’s not a satanic system of thought at all, but…

AP: It laid the foundations.

PF: Laid the foundations exactly.

AP: Yeah, especially the theoretical foundations for esoteric Satanism.

PF: Yes definitely. On the other hand then, if you want to find a complete system of satanic thought, someone who is consistently using the symbol of the Devil, then we have to move ahead a few years in time and also shift location to Berlin where we find a very curious character called Stanisław Przybyszewski who was a Polish, decadent, proto-expressionist author also an art critic and a very important figure in the art world, who formulated a system of satanic thought where Satan was the central symbol, a symbol of creativity and of evolution. So, in a way, similar to Blavatsky, even though he didn’t particularly like Blavatsky, actually. So that is, what I would say, the first system of satanic thought. So in a strict sense then Stanisław Przybyszewski would have been the first Satanist.

AP: And when did the esoteric Satanism… so after him, how did it develop?

PF: I mean, Stanisław Przybyszewski was interested in the Occult, in Parapsychology and especially in medieval black Magic and things like that. But he was quite dismissive of most of the esoteric traditions of his day. So, his system was not an esoteric system of Satanism but rather something in between. And suppose we’re thinking of a well-developed satanic, esoteric system of thought. In that case, that only happens again a few years later, and this time in Copenhagen, where there is a relatively obscure local eccentric called Ben Kadosh. His real name was Carl William Hansen, a member of a great variety of initiatory societies and Masonic orders and things like that. You could almost say that he sort of collected degrees in various esoteric orders. He came up with a system, an esoteric system of thought, that he presented in a pamphlet that he sought to distribute widely, where he places Satan as the central figure in an esoteric system. Of course, we know that his ambition was to recruit people for his satanic circle. But it’s quite uncertain how many people did participate in the activities. We know that he had a few adherents and some rather wonderful visual material produced by members of this circle that’s preserved at the Royal Library in Copenhagen. So we know there was some activity going on, but we don’t really have that many details, so I would say it is the first satanic organization in a sense, but, of course, it’s a minuscule one.

And then, if we move a little bit further ahead in time, we find in Germany a group called Fraternitas Saturni, the Brotherhood of Saturn, and this group is, perhaps, not one that you could describe as satanic per se. But they did identify Saturn as the central symbol of the order with Satan and perceived Satan as a sort of initiator in the tradition of Blavatsky. And in this group, they also celebrated a type of Luciferian Mass. So they had some sort of ritual practice going, and they had this identification of their primary symbol, Saturn was Satan. And we could at least say that there was some satanic content in this fairly well-populated order even though they were working with many symbols and entities simultaneously.

And then, in the 1930s, we have the first instance of a more or less public satanic, esoteric group which was run by a woman called Maria de Naglowska, and this group organized a type of Black Masses that were almost like theatrical events to which the general public could have access by paying a fee. She also published a magazine detailing her rather idiosyncratic, esoteric, satanic ideas, and I put that within quotation marks because her ideas are also very much anchored in a Christian worldview where Satan is primarily an important part of God’s plan. So that’s his function. It’s not the lauding of Satan that comes to the fore but rather the important function that Satan supposedly has in God’s grander plan.

And then there are several other smaller groups, for example, one in the, I think, the late 50s or early 60s in Toledo, Ohio, in the United States, and all these groups predate what would be often perceived as the foundation of modern Satanism with the 1966 founding of the Church of Satan in California by Anton LaVey. And I think the rest of the story is a bit more well-known that this early history of Satanism has been fairly obscure up until recently.

AP: Yeah, I think that now people tend to distinguish between theistic and atheistic Satanism. Would you make the same distinction when it comes to the contemporary satanic milieu or do you think that it is an oversimplification?

PF: It is, to some degree, an oversimplification. If you look at someone like Anton LaVey, of course, he is primarily an atheist. Still, some passages can be seen as a possible leakage of a theistic tendency into his Satanism, where he speaks, for example, of Satan as a dark force in nature. But on the whole, it’s an atheistic system, which has been very much emphasised by those handling LaVey’s legacy. And then taking the Church of Satan into our century. But I mean, these distinctions for me, as a scholar, are just something that we would have to decide on a case-to-case basis what’s useful for what we want to do as scholars, right?

AP: Yeah, that’s always the distinction between the emic and the etic.

PF: Yes. yeah

AP: Yeah, I will put it on screen, what the definition is but yeah, the emic perspective is how insiders how practitioners would define themselves and the etic perspective or the etic definition is how scholars would define what practitioners do and in some cases, the two are not the same.

PF: No, absolutely. There can be a discrepancy, but in some cases, depending on what you want to do in your scholarly project, it might be better to stick with the emic definitions and not come up with your own. It all depends on what goals you set for yourself for that specific project.

AP: I was also interested in knowing about the relation between Satanism and the Left-Hand Path. Yesterday we mentioned that and the connection with Kenneth Grant.

PF: Sure. I mean, that’s a complicated history. To some degree, the Left-Hand Path can be perceived as an umbrella term that will also encompass Satanism. Still, the interpretation of the Left-Hand Path, which is, of course, an Indian concept to begin with, in this Western occult milieu is something that, partly, must be understood against the background of Satanism – in a way, it’s a post-satanic development. So Anton LaVey, for example, uses the term Left-Hand Path, and it’s also present in popular culture before LeVay as an alternative name for Satanism. So you find that in Dennis Wheatley, the British author of occult-inspired, trashy fiction, he uses that in his fiction and the term itself doesn’t become broadly used within the esoteric milieu as a self-description until… a bit later after LaVey came up with the term in the first place in the “Satanic Bible,” it had been floating around obviously, for example, in Theosophy. But Theosophy used the term as a derogatory one, inspired by colonial constructs of the Left-Hand Path as a sort of antinomian, transgressive, negative practice that they would not recommend any proper Theosophist to engage with.

AP: And some contemporary practitioners have become a living God, yeah, sort of statement as part of their practice.

PF: Sure.

AP: So basically it is not really that Satanism comes out of the Left-Hand Path but more like the Left-Hand Path that developed out of Satanism?

PF: To some degree. We could see it as a post-satanic development even though the term was floating around with people like Kenneth Grant before that.

AP: And what are the forms of Satanism that are contemporary, present at the moment?

PF: Of course, we still have a strong Church of Satan present, but there are so many varieties. It’s a really rich field of study because of that and that’s one of the first things you always have to explain to students or journalists, that there’s not just one form of Satanism. Because you will often get questions like, so, is it like this in Satanism? And then you have to explain that there are, you know, various Satanisms, so in the plural. But, of course, we have the Church of Satan still around; we have the church of Satan offshoot, Temple of Set, which, perhaps, should not be designated Satanism proper because they re-frame the figure of Satan using different terminology. And we have the quite peculiar form of Satanism that arose in the Nordic countries in the late 80s and early 90s, with the black metal Satanism, which is extremely anti-social and transgressive and was famously connected to several murders and a great number of church burnings, in the Scandinavian countries, in the early 1990s. This is a very strongly theistic form of Satanism, also emphasising Satan as an evil figure, which is quite interesting because that’s something you don’t often find in Satanism, generally. Most Satanists would consider the Devil to be the good guy. Still, these folks instead emphasised the evil nature of Satan and embraced that. And then we have the politically progressive Satanism that is now taking the world by storm. And I would say that that’s probably the biggest form of Satanism today; it’s something that’s growing at an immense pace, which has a real impact as well in more mainstream contexts in a way that we haven’t seen with Satanism in quite a while.

AP: Do you think that Satanism is necessarily Christian or linked to Christianity? I’m thinking about this because I know there is a controversy in Italy. After all, there is a group of Satanists that would like to be defined as Pagans. You know, the pagan community doesn’t want to accept them as Pagans, and that is perhaps a different matter whether they, you know, they classify as Pagans or not. And I would say they don’t, and I know that you agree because we had a private conversation about this, but that just made me think because one of the arguments that the pagan community was using was that Satanism is inherently linked to Christianity. After all, since Christianity invented Satan, then there wouldn’t be any Satanism without Christianity. So, do you think that Satanism is inherently and inextricably linked to Christianity, or would you disagree with that?

PF: I would say historically, it’s quite obvious that it appears as a counter-discourse in opposition, direct opposition to Christianity, that that’s the root of Satanism. On the other hand, there have been attempts by Satanists to free themselves from this, and in many cases, this has been done using a re-framing of the figure of Satan. The Temple of Set would be an example of that. In one sense, you could say that the Temple of Set is a pagan or a neopagan group because they’re using the Egyptian god Set instead of Satan, claiming that the prince of darkness, formerly known as Satan, conveyed to the group’s founder, Michael Aquino, that he did no longer wish to be known by the name of a Hebrew fiend but rather by the name of his first manifestation to mankind, which would have been Set in ancient Egypt. So, in a way, they still retain the identification of this entity with Satan. Still, they re-frame it by employing this ancient Egyptian name instead. So, I mean, it’s not a clear-cut issue. Still, generally speaking, I would say that it’s difficult to entirely divorce Satanism, using the name Satan as their primary focus, from Christianity.

Perhaps one could also argue there are elements of Paganism that are still Christian, and they have been sort of employed by Pagans anyway. Still, yeah, that’s it’s a different topic, I guess.

AP: And then I wanted to ask you about the difference between… because you know, so far, we’ve been talking about Satan as equivalent to the Devil and Lucifer. Still, I know that I will get comments about this because I have a few other videos on Satanism and one of the recurring comments was, oh, you’re using Satanism and Satan as synonymous to the Devil and Lucifer, but they are different entities. So, I am aware that there are practitioners who see a difference between these entities. So, could you expound more than that?

PF: Even with Theosophy, there were attempts by Theosophists to divorce these figures from each other. As is well known, the Theosophical Society published a journal called “Lucifer”, and in the editorial for the first issue, they are quite adamant that this is not the Devil, that’s not where they got this name from, it is Lucifer – the bringer of light. On the other hand, in the same editorial, there are references to the noble rebel of Milton and such things that make it quite clear that there’s still a connection being retained here. And if we look at Blavatsky’s writings that connection is still there. So it’s a bit of a way of, perhaps, keeping your back free in anticipation of the criticism you expect. But at the same time, of course, if you choose a name like Lucifer, you want to taunt the Christian somehow, right? So, it’s intended to be a provocation. I think it’s pretty much the same way with most groups using the figure Lucifer and saying, of course, this is not the Christian Devil; it’s a different entity. But, of course, you could have gone with a different figure or a symbol or name for it. You still want to sort of provoke, in a sense. But I mean, it’s a matter of theology within these groups, and it’s not my role as a scholar to say that it’s wrong or right to divorce the figure Lucifer from Satan. If they interpret the entity that way, that’s their prerogative. I’m only here to analyse that, perhaps looking at why they would.

AP: Yeah, yeah, that’s what I was interested in, the underlying reasons as to, you know, why practitioners separate Lucifer from Satan, from the Devil.

PF: Sure, I mean, often, it’s because they want to distance themselves from some of the negative symbolism attached to the figure of Satan. Perhaps they want to put an emphasis on the initiatory aspect and the light-bringer symbolism rather than all the dark stuff that’s also bound up with Satan historically. So that could be one reason.

AP: Could it also be that in some cases they want to divorce the figure from Christianity or highlight…?

PF: Sure, absolutely and it’s used that way for example in the various currents that have been labelled Luciferian Witchcraft.

AP: That was another thing I wanted to talk about.

PF: Yeah we consider that is very much within those groups but of course, the rhetoric of Christianity having, somehow, twisted originally pagan figures into satanic, demonic things. That’s something that’s present within Satanism as well. You find with Anton LaVey, he says the same thing in the “Satanic Bible” about the figure Lucifer, actually.

AP: Can you talk about Luciferian Witchcraft? What is Lucifer in Witchcraft and when and how they started?

PF: Again, this is something that has a variety of forms. It’s sometimes difficult to make general statements about this. Still, let’s look at the historical development of this phenomenon. We find that it comes really as a reaction to Wicca, quite early on, in, like, in the late 50s when various sort of competitors to Gerald Gardner start appearing on the Wiccan scene, trying to create legitimacy for themselves and their tradition by making claims of, for example, being hereditary Witches who represented something more ancient than the stuff that Gardner came up with. With some of these figures, there was a turn towards Folkmagic and darker forms of Folkmagic, which would sometimes then encompass the figure of the Devil in some sense. Several figures worked with this, but there wasn’t really a tradition being formulated clearly at this time.

But these ideas seem to have been floating around in that, shall we say, early post-Wiccan or alternative-Wiccan milieu. And this, later on, became more well known to the general public, I would say, primarily with the 1970 publication of Paul Huson’sHuson’s book “Mastering Witchcraft” and this book combined what is Wiccan material, with things taken from more, shall I say,, High Magic or Ceremonial Magic and also some satanic content. For example, there’s a self-initiation ritual in that book where you’re supposed to read the Lord’s Prayer backward, so that’s quite blasphemous. And that was something that others also picked up on.

There’s, for example, a small Swedish book that came out a few years later that picked that ritual up and incorporated it into a sort of Wiccan context. So that’sthat’s one of the main impulses for this. Still, many people started working with this type of combination of Witchcraft and then elements from Wicca and Ceremonial Magic and Folkmagic and some satanic symbolism. People like Michael Howard and, of course, Andrew Chumbley and the whole tradition of sabbatic Witchcraft, which also drew on Austin Osmond Spare and especially the symbolism of the Witches Sabbath and a sort of shamanistic, if you will take on, on what Witchcraft is and this then involved the whole symbolism of the devilish, sabbatical rites that are known from the early modern period but of course, reinterpreted the whole thing into something different but retain some of the satanic symbolism of this.

PF: Well I mean again…

AP: Do they follow the Wheel of the Year?

PF: It’s such a diverse set of traditions that it’s impossible to make a general blanket statement. But yeah, definitely, some of them do, and many of these traditions retain much of the ritual structure and symbolism from Wicca.

AP: So is it a combination of Wicca, ceremonial high magic, with Lucifer at the centre as a core deity?

PF: In some cases, it is, and in some cases, it’s rather the case of having the Devil or a Lucifer, with clear traits of the satanic, as part of a larger pantheon. So it’s not necessarily that Satan is sort of centre stage. No, I wouldn’t say that. And also with the ceremonial high magic thing, which is a bit of an arbitrary distinction, but even with that many of these traditions have come to emphasise Folkmagic much more. So the magical practices of Cunning Folk from the traditional, agrarian, European societies. So, there are many strands within this broader tradition of Luciferian Witchcraft. There are also differences between the US, the UK, and other countries.

AP: And in Luciferian Witchcraft do they employ the figure, the entity of Lucifer in a theosophical sense, like the bringer of the light or as a rebellious figure?

PF: There can be a bit of both. And of course, with a figure of Lucifer as a bringer of gnosis, that also goes back to ancient Gnosticism, and that’s something that Madame Blavatsky refers to quite a lot in her work, this supposed reinterpretation by Gnostics of the serpent as a bringer of gnosis, which we can find in some actual gnostic texts but where the, shall we say, satanic connotations of this were, of course, very much overemphasised by the early Church Fathers who wrote texts about what Gnostics were up to. So that’s a tradition that’s present. Still, these sorts of Folkmagic traditions also have very little to do with something like Theosophy or Gnosticism. In these folk traditions, the Devil would be a figure you could turn to for magical purposes, to get help in specific situations where God or the church would be very unlikely to help you, for example, this thing with childbirth, where women were supposed to give birth in great pain as a punishment meted out by God. You find in many countries folk medical practices where you turn to the Devil for help to alleviate your pain during childbirth, of course, often according to folklore with horrible consequences – your firstborn son would become a werewolf, things like that.

AP: Yeah and why would the women do it anyway if they believe that the firstborn child would turn into a werewolf? Why would they still resort to the Devil to help them with pain?

PF: One interpretation could be that it was out of desperation. Another one could be that there’s a disconnect between the actual practices and beliefs surrounding these specific rights and then the people who would have helped out with that and the, shall we say, more legendary elements in folklore, sort of, the tales spun around these practices as something you’d tell around the campfire.

AP: Oh, this is interesting. I enjoyed this conversation. Thank you very much, Per, for being here at Angela’s symposium and, yeah, obviously, for you guys watching this interview. Let me know in the comments section what you think about what we said and whether you have questions. I will do my best to answer them. Don’t forget to check the info box for contact details of Per’s publications. So, thank you very much for being here at Angela’s Symposium.

PF: Thank you for having me, Angela.

So, as a bonus to this interview, I thought I would read you a short story and it’s a short story written by me. Aside from my scholarly career I also write fiction and in my debut collection of short stories “The Tree Of Sacrifice,” which came out in 2020, there are quite a few stories drawing on folk magical and satanic symbolism. So this is a story which is called “The Annihilator” and somewhat unromantically, I have it as a PDF, the English translation, here on my phone. So I will read it to you from my phone.

The forest surrounding Hwitmo Mountain burned down in 1834. Everything was consumed save for a few resilient pines with deep roots which remained charred and mangled. Most of the forest floor itself had been destroyed and all the animals were gone. For a long time thereafter, no birds were heard, they avoided the lifeless area and did not fly into it. Eventually, a few species of plants started to grow, morels and certain mushrooms flourished in the ashes, and liverwort slowly began to rise up but the people, like the birds, kept their distance. It was known that the burned forest was dangerous the remaining trees could fall, silently and without warning. Below the ground, there could, several months, later still be hollows filled with burning coals that one might step in.

Albertina had vivid dreams that she would relate to Isaac. He took them in deadly earnest and considered her a prophetess. Ever since they had begun spending their days among the charred trees and ashes she had dreamt of a figure called the Annihilator. He resembled the Devil from the church murals, black and hunched with horns. In these dreams, he moved across the land alongside the forest fires. After the fires he would allow something new, like the morels and liverwort, to begin to grow where the old life forms had been annihilated. The children began to speculate if something similar could be done for human beings. They decided to set another forest fire and let themselves be consumed by it in the hope of being resurrected in new faultless bodies.

One early morning they gathered baskets full of birch bark in the forest close to the village. They laid it out in circles around old dried-up broad-leaf trees. Isaac had stolen a hymn book from the church from which they now ripped out pages and set them on fire. The children ignited the birch bark with the burning song verses and soon the trees also burned. It was not long before the fire approached the village, the heat and smoke made them dizzy, their eyes watered. Through the tears, they could suddenly see the Annihilator standing in the midst of the flames. He smiled softly and reached his hand out towards them, they grasped it gratefully and followed him. To their great surprise, the fire did not burn them, it felt like soft caresses. The Annihilator told them that they were not the ones who would be consumed by the flames, Isaac and Albertina were perfect just as they were. However, all the people in the village who had rejected them would be turned to ashes and coal. Other, better people would take their places.

The children were at first saddened that this included their parents but remembered all the beatings and harsh words that they had received from them, thus they laughed along with a hunched, friendly figure as farm by farm disappeared into the rolling sea of flames. The people’s screams became a wonderful hymn to their ears and never again did Isaac or Albertina wish for faultless bodies.

This is it for today’s video. If you like my content and want me to keep the Academic Fun going please consider supporting my work with a one-off PayPal donation, by joining Memberships or my Inner Symposium on Patreon where you will get access to our Discord server, monthly lectures and lots of other perks, depending on your chosen tier.

If you liked this video, don’t forget to SMASH the like button, subscribe to the channel, and activate the notification bell so that you will never miss a new upload from me. Also, leave a comment and share this video with your friends because that’s how we create a community and grow as a community. So I really appreciate it if you do that. As always, stay tuned for all the Academic Fun.

Bye for now.

FOLLOW PER FAXNELD:

Instagram @perfaxneld

Twitter: @perfaxneld

RELEVANT PUBLICATIONS

- Per Faxneld. Satanic Feminism: Lucifer as the Liberator of Woman in Nineteenth-Century Culture, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

- Per Faxneld & Joan Nilsson (eds.). Satanism: A Reader, Oxford: Oxford University Press, in press.

- Per Faxneld & Jesper Aa. Petersen. The Devil’s Party: Satanism in Modernity, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Per Faxneld. “Bleed for the Devil: Ritualized Self-Harm as Transgressive Practice in Contemporary Satanism, and the Re-enchantement of Late Modernity”, Alternative Spirituality and Religion Review, Vol. 6, No. 2, 2015, pp. 165–196.

- Per Faxneld. “Secret Lineages and De Facto Satanists: Anton LaVey’s Use of Esoteric Tradition”, in: Egil Asprem & Kennet Granholm (eds.), Contemporary Esotericism, London: Equinox, 2013, pp. 72–90.

- Per Faxneld. “Intuitive, Receptive, Dark: Negotiations of Femininity in the Contemporary Satanic and Left-Hand Path Milieu”, International Journal for the Study of New Religions, Vol. 4, No. 2, 2013.

- Per Faxneld. ”The Devil is Red: Socialist Satanism in the Nineteenth Century”, Numen: International Review for the History of Religions, Vol. 60, No. 5, 2013.

- Per Faxneld. “Blavatsky the Satanist: Luciferianism in Theosophy, and its Feminist Implications”, Temenos: Nordic Journal of Comparative Religion, Vol. 48. No. 2, 2012

- Per Faxneld. ”Feminist Vampires and the Romantic Satanist Tradition of Counter-readings”, in: Gabriela Madlo & Andrea Ruthven (eds.), Woman as Angel, Woman as Evil: Interrogating Boundaries, Oxford: Inter-Disciplinary Press, 2012, pp. 55–75.

- Per Faxneld. “The Strange Case of Ben Kadosh: A Luciferian Pamphlet from 1906 and Its Current Renaissance”, Aries: Journal for the Study of Western Esotericism, Vol. 11, No. 1, 2011.

- Per Faxneld. ”Satan as the Liberator of Woman in Four Gothic Novels, 1786–1820”, in: Maria Barrett (ed.), Grotesque Femininities: Evil, Women and the Feminine, Oxford: Inter- Disciplinary Press, 2010, pp. 27–40.

First uploaded 16 Jul 2022