Dr Justin Sledge JS: Hi folks welcome back to another episode of Esoterica losing a dozen subscribers by defending a curmudgeonly, mid-20th century German guy, starring Dr Angela Puca of Angela’s Symposium and Theodore Adorno. So welcome, welcome Dr Puca, welcome Angela. Thank you for coming back and talking with me about this.

Dr Angela Puca AP: That I don’t like very much. And there is one of my Patrons who always makes memes of me eye-rolling.

[Laughter]

JS: That’s funny. Well, I’m gonna believe that the fact that you dislike Adorno so much and you keep coming back means that you like me. So I’m gonna take that as for all the reasons that you dislike Adorno I’m gonna take the fact that you’re willing to put up with him to hang out with me, and at the least throw shade on him, I’m gonna take that as a sideways compliment.

[Laughter]

AP: Yes, it is a compliment, Justin. But I also think that it’s interesting to discuss. I kind of like also to enter into arguments that I disagree with so that you can unpack things and understand things better about the way you think and, I don’t know, I find it very educational.

JS: I think so too and even if I agree with him in some ways there are lots of ways that I don’t. And I think part of what also was just good is that just trying to understand what the hell he’s talking about is really intellectually challenging. It’s not just like I disagree with him or agree with him it’s like, oh yeah, this is a really important thinker who writes in a very obtuse way. How do you actually unpack what he’s saying and figure out what he’s saying, to agree with it or not? So in that way, I think he’s… I like to read Adorno for the same reason, the same masochistic reasons I like to read French mid-century Continental thought and Deleuze or whatever. These kinds of people.

AP: Cassirer, I find him very difficult. Husserl.

JS: Husserl? Husserl’s not that bad. I mean, I guess it depends on what he’s writing. Ideas one and two aren’t too hard. I guess it’s also like if you kind of know what he’s up to then he’s not too terrible, or a Heidegger or something the late Heidegger is just like, I’m going to read mysticism, I’ll just go read Meister Eckhart or something, I don’t know. Take that Heidegger – at least the late Heidegger, I like the early Heidegger – he’s just fun.

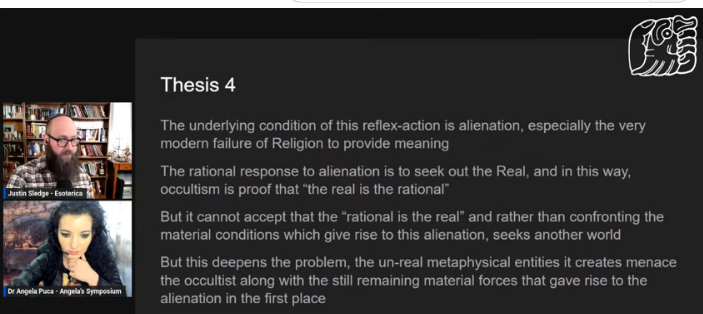

But all right, well folks also I’ve gone I’ve done a thing. What I’ve done, and is to, maybe, help us a little bit in terms of keeping track of Adorno’s arguments. I’ve actually gone through and summarised them and rendered them in argument form. I’m fairly confident I’m getting the drift of what his argument is. You know, maybe if an Adorno expert wants to say I’m getting it wrong. But I think I know his basic argument. And so what I want to do is just summarise up to thesis three as to what his positions are because I think that a lot of the comments I see are people criticizing Adorno because they just don’t like what he’s saying. But I don’t know that we’re totally on the same page about what he’s saying. And I think that being on the page about what he’s saying is he’s not saying things like occultists are stupid, that’s not what he’s saying. So it’s really important to get what he’s after and what I want to do is summarize where we’re at up to thesis three and then we’ll pick up with thesis four and that’ll give us sort of a background to where he is.

I’ll try to go through these quickly so we’re not taking a bunch of time on this. Can I cycle from here – no I can’t. So let me move this tab over here. All right, so I had to do it like black and white, super stark because it’s like…

AP: I find it interesting that you called it ‘on’ Occultism instead of against.

JS: Oh, that’s right, yeah. I should change it. There’s like a secret thing I’m communicating at some kind of…

AP: Maybe I’m persuading you live stream by live stream.

JS: Maybe, or maybe I just take his critique to be so ipso facto true that I don’t even think of it as against them. It could be cut either way.

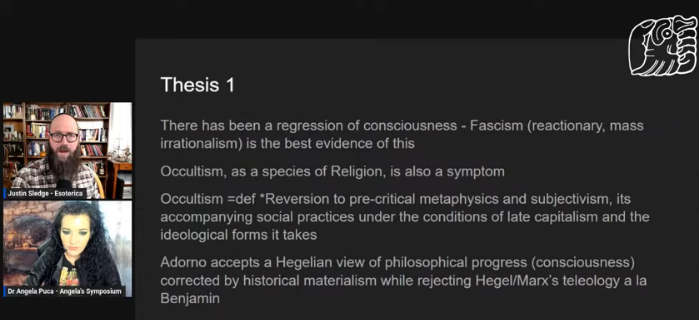

So at any rate, he starts off famously, right, that there’s been a regression of consciousness and the regression of consciousness that he’s most interested in here is fascism. And this is what he would call a reactionary, mass irrationalism and that regression of consciousness takes primarily the form of fascism. Now he doesn’t say that Occultism is a regression of consciousness he says that it’s a symptom of that regression, right. So it’s in itself not a regression, it’s a symptom of the regression. I think that’s a very small but important detail. So his general track is going to be to attack Occultism primarily along the lines of the general attack of historical materialism on religion but he thinks that Occultism is a very particular species of religion and that, in the way that it emerges in sort of late capitalism, it’s going to have a particular form – and he’s attacking that particular form. So if you think of religion as the genus he’s attacking, he’s using historical materialism to attack religion but a particular kind of attack he’s leading on Occultism. And I’ve given an “=def” for Occultism obviously that’s not a real “=def” because this is not an analytic definition of Occultism and that’s why I put the little a little asterisk there, to be, like it’s reconstructed and it’s not analytic. But welcome to me doing analytic philosophy, that’s how I was trained. And this is where I think I might disagree, Angela, where the idea that he’s attacking sort of pop Occultism. I’m increasingly not convinced of that now.

We can talk about why later. But I’m trying to give him a definition of Occultism, basically, build out of what he was arguing. And the way I define it is the reversion to pre-critical metaphysics and subjectivism, its accompanying social practices under the conditions of capitalism and the ideological forms it takes. Ideological there being the Marxist jargon for that term, right. I’m not using ideology and just things you believe but ideology in the Marxist way that that term gets used. If you’re familiar with Slavoj Žižek that term, that way of using the word ideology should have maybe capitalised it. I think that’s what he means by Occultism, right. That it’s a combination of a reversion of critical metaphysics, subjectivism and the accompanying social practices that emerge under late capitalism and the ideological forms it takes. And it’s also just to point out that Adorno accepts a Hegelian view of philosophical progress, that’s what he means by consciousness, right. You can disagree with him and if you disagree with him, basically you disagree with everything else that comes later. So he thinks that a Hegelian theory of philosophical progress is true if it’s checked by historical materialism. But what’s really important is that he rejects both Hegel and Marxist teleology.

And he’s picking that up from Benjamin so folks who know the Angel of History stuff from Benjamin that’s really playing a role in Adorno’s uptake of historical materialism. So he accepts historical materialism, he accepts a critique of capitalism, he rejects Marxist teleology – it’s very important, very important.

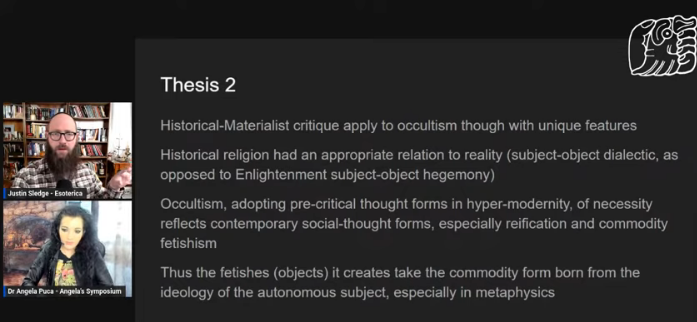

So thesis two, right: the historical materialist critique applies to Occultism but with unique features because Occultism is a particular kind of religion. So he argues that history had an appropriate relationship to reality, that’s the subject-object dialectic, right, that there was nature in us and there was an appropriate relationship between us and nature or us in the divine that was a subject-object dialectic and he opposes that to the dialectic that emerges in the enlightenment – the dialectic of Enlightenment where there’s subject-object hegemony. Which is to say the subject attempts to achieve Heerschaft or hegemony over the object. What’s going to happen is that as the theses develop he’s going to argue that what Occultism does is that it reverses that, is that the subject-object relationship – the dialectic is broken and the subject is sort of loose in a certain kind of way. So we’ll get to that in a minute so what Occultism does is it adopts pre-critical thought forms in a hyper-modern situation and of necessity because it’s adopting those in a hyper-modern context, it’s going to take contemporary social thought forms, especially the thought forms of reification and commodity fetishism.

Also, it’s going to take the form of a division of labour. So he thinks that those three things are operating in Occultism in a very, very exacerbated way and even in a way that they don’t operate in religion or general religion – Catholicism, Judaism, Islam, even less so Islam, and stuff because it’s less connected to modernity in his mind, I think. So reification, commodity fetishism and the division of labour. So keep those in mind and what he thinks happens is because this Occultism is developing in this hyper-modern context. The fetishes, the objects that it creates take the commodity form – that should be unsurprising – that’s classic sort of Marxism stuff. But the ideology that emerges is an ideology that is also typical of late capitalism and liberalism, which is the ideology of the autonomous subject.

So he argues in thesis two, that the fetishism of the commodities creates commodities that are fetishes, the fetishes become commodities, and these metaphysical entities become fetishes. They take the form of the commodity and the kind of ideology that develops is the ideology of the autonomous subject, and this is especially true in metaphysics, right. And that’s what we talk about, we mean pre-critical metaphysics. Pre-critical metaphysics is the idea that you can just do metaphysics without having to do the work of folks like Kant and Hegel. So the idea that you can ad hoc do metaphysics, what some people now call guerrilla metaphysics or object-oriented ontology, all that kind of stuff. Adorno would hate that stuff.

So if you’re familiar with OOO – object-oriented ontology all of that would be to his mind pre-critical metaphysics. Which is not surprising, by the way, that so many people, who are interested in OOO and the kind of world that Nick Land and that school come from are also crossing over into the occult world as well. That is very interesting to me and I think Adorno predicted it really, really well. Like really interestingly predicted that outcome.

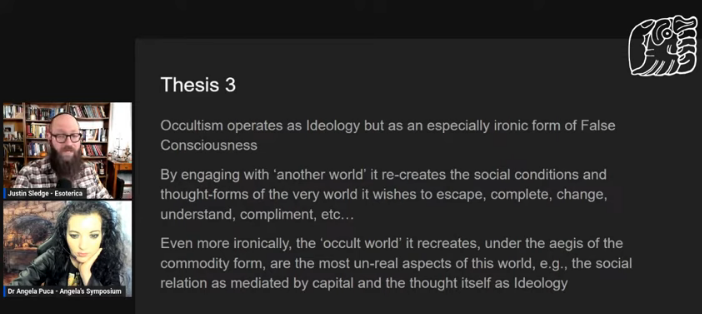

Thesis three, which brings us up to where we were last time, right? So he argues that Occultism operates as ideology – that’s not surprising, as religion operates as ideology. We should be totally unsurprised by that. But it operates in a uniquely ironic form of false consciousness, right? So again thinking back to the German ideology, Marxist critique of consciousness, right. The German ideology and his critique of false consciousness and what Adorno argues for are that by engaging with another world and I put another world here in scare quotes because he doesn’t think it’s real because it engages in another world that’s filtered through the medium of modernity and late capitalism it’s going to recreate the social conditions and thought forms of the very world that it wishes to escape or complete or change or transform or redeem or whatever term you want to use. So the world that it tries to escape to or create or engage with is just going to reproduce the exact same thought forms and social relations in that world. Whether it’s the world of the Gods, the world of spirits or the ancestors or whatever, that it actually is trying to get distance from in this world. And what’s even more ironic and that’s just true of religion in general, religion always recreates the thought forms of the world that it comes from.

A great example of this is the Goetia, right. When the writer of the Goetia imagines the world of demons look at the social forms it takes. It’s just a bunch of aristocrats, it just recreates feudalism in another world because that’s the world it’s coming from. To get Dukes and Barons and all that stuff and you’re like why would there be Dukes and Barons and blah blah Knights and stuff? Well, of course, there would be because that’s the world you’re coming from and when you think of powerful people you recreate that in another world. So what he’s going to argue here is the exact same thing is going to happen with the so-called occult world. But this is where he thinks this is especially ironic given the world of Occultism is that the world that it creates under the commodity form, is interestingly enough, the least real aspect of this world. The fetishism of the commodity means that it recreates over there, in the other world, a world of commodities. And commodities are, according to Adorno and Marxism, the least real aspect of our world. They’re the aspect of our world completely created by human beings and its social relations are mediated by capital which we invent and thought itself as ideology. So for him, the claim that the occultists have access to a more true world is rendered all the more ironic considering, but the least true elements of our world are the elements that go into constructing that world. And he thinks that is the real, that’s not only the irony of it but it’s the danger.

Because what is in our world, is completely false, the commodity relation gets recreated in another world but that world now is the unique place for which people gain gnosis or truth or religious truth or the wisdom of the ancestors or the akashic record or whatever. And it becomes the fact that the least true thing, the most false thing in our world is now transcendentalised and made the source of absolute truth in another world. And Adorno thinks that it’s not just ironic – it’s terrifying. And so that’s very dangerous, right, very, very dangerous and we’ll see how it works out in a very dangerous way as we get into thesis four. That’s where I think he lands by the third thesis, I think that’s where he lands, where we wrapped up last time. Maybe we got through thesis four, Angela. Are you sure we only got through thesis three?

AP: No, I’m not sure.

JS: Maybe we can start with thesis four.

AP: No, I don’t remember doing thesis four because there’s Kafka and Latin and I don’t recall that at all.

JS: All right, so the Kafka and the Latin remind us. Okay, does that summary sound correct to you? Not correct in the sense that you agree with it, obviously but correct in the sense that that is what Adorno seems to be doing.

AP: I think so and to me the first thesis tends to focus on the instrumental reason the second one on commodification and the third one on the concept of regression. Yeah, there’s also the element of him thinking of the occult as something that is a pre-rational understanding of the world.

JS: I don’t think he thinks it’s pre-rational, I think he thinks it’s a uniquely modern form of irrationality – that the regression is happening. It’s not like the occultist is regressing back to a previous time but they’re regressing in a uniquely modern way. The regression is happening in a uniquely modern context. For instance, with the exception of some maybe strange people I don’t know anyone who really believes in Agrippa’s metaphysics. Like no one, aside from flat earthers or something, no one’s a geocentrist and Agrippa’s system really only works at some level with a geocentric worldview. It assumes the geocentric worldview, so stuff like that I don’t think that no one’s regressing in the sense that they’re going back to thinking… like no one is believing in the active intelligence type of thing. This is kind of what our stellar, maybe some people believe in stellar race but most people are not going back to pre-critical Medieval thought forms. I don’t even know if that’s possible. It’d be interesting if you could do that. I wish I could believe in active intelligence, it’s one of my favourite ideas ever. Or like I wish I could believe in Stoic metaphysics or Stoic physics for that matter.

AP: I’m going back and forth between your slide and the theses by Adorno.

JS: Can we share this with you, Angela?

AP: Oh, it’s fine. I mean I can focus on what I’m seeing now which is thesis three. I think it is a good summary, although I still see a lot of biases in a way. I mean a very specific understanding of Occultism, which I think you expressed in slide one.

JS: And again I’m not saying this is what Occultism is, I’m saying this is what Adorno thinks it is. And this is me taking going through all of the… every time he seems to give something like a definition of what he thinks it is, I’m trying to pack in what he thinks it is. Obviously, this is not what occultists think they’re doing because, I mean, they wouldn’t be doing it if they thought they were doing this, I don’t think. And again whether it’s fair or not it’s probably not fair. But I think that this is basically what he thinks is happening.

JS: I agree in a general way, yeah, I agree that all of these things are bad, that what I should say is incorrect. Like pre-critical metaphysics is a mistake, like reverting to that is not a thing, you can’t just do metaphysics. I do agree that Kant is Right basically in that.

AP: What do you mean there by ‘pre-critical?’

JS: That you could that we have…

AP: Was it what I was saying about the pre-rational, his perception of it being pre-rational?

JS: No it’s the idea that sort of the Kantian like, you know, when I say pre-critical, I’m just meaning like sort of pure, like the way that Kant criticised Leibniz, right. That we don’t have apperception of the metaphysical world and therefore we have to do some transcendental philosophy in order to get access to the metaphysical world and that will always be limited. And we can argue about what it’ll be limited by. Kant has his the furniture of the mind as he puts it, right that does the limiting. But I think that the argument is that, I would say, any return to a pre-critical metaphysics is just not viable. That is to say, we don’t have direct apperception of metaphysical truths. We may disagree about that and there are people actively now in philosophy who disagree with that as well. As I said the object-oriented ontology people.

AP: Yeah, I guess I was just thinking whether that is what happens in Occultism. I’m not convinced that that is what happens in Occultism. So if we’re thinking here about a pre-critical metaphysics and subjectivity meaning pre-critical in Kantian terms, right. So it would mean a metaphysics that is not criticised in a Kantian sense, it is perceived as something that you directly experience.

[Justin Sledge nods]

AP: Okay, so I would say that there are some traditions where that is the case and other traditions where it is not the case. So for instance, in Shamanism, that would be true because there’s very much the sense of the direct experience with the spirits and the divine. But I’m not convinced that that is what happens in other forms of Occultism.

JS: I mean I’d be curious to see, I’ve never seen a theory of Occultism that includes a critical apparatus à la Kant. Like what we can know and what we can’t know and why we can’t know those things, like from logic, like philosophically argued. I mean it’d be interesting to see a theory of the occult that offers a critical metaphysics, that offers a critical apparatus to its metaphysics. I’ve not seen that, I would like to see it. But someone like Agrippa, Agrippa just comes right out and starts doing a metaphysics – there’s no critical apparatus. I mean he thinks the gnostics, they think that you can just get, you know, there’s no barrier, there’s no mediation or there’s no mediation once you break through the false reality of the physical world or whatever.

AP: What about Theosophy?

JS: I mean they think you can get access to the akashic record. I mean that’s just like straight-up everything. I mean that’s exactly the kind of thing that Kant writes against, right, in the footnotes of the group of the first critique precisely because of the work he had done with you know on Swedenborg and Jakob Böhme. I mean that’s, in fact, one argument that can be made that early Theosophy, Jakob Böhme and its uptake in Swedenborg is precisely the reason why the first critique was written because Kant was working on that stuff, you know, whatever the Dreams of a Spirit Seer or whatever and he was really interested in those claims and ultimately the first critique is meant, in some ways, to prevent that. The third critique’s a little squirrelly there because sometimes he seems in the footnotes to say you can have direct apperception of at least aesthetic objects. But there’s a lot of debate about that but even still there’s not much light between the first and third critiques there.

And again I say reversion to pre-critical metaphysics but someone can also just say, no I’m going to do object-oriented ontology and there are people out there doing it and I don’t give a damn what Kant says.

But I think this is the argument. Think again, Adorno. If there’s an Adorno expert out there feel free to critique my summary but I’m fairly confident this is what he’s arguing. What’s also interesting is now that I’m reading it again, rebuilding the argument, it’s a lot tighter of an argument than I thought it was at first.

On Arthur Sleep, yeah it’s not a question of imagination because Kant thinks the imagination is an infinite category. The question is not whether your imagination is infinite, it is. The question is whether or not it is a transitional structure of thought and he thinks that it is incapable of doing that. And that’s a huge difference between modern philosophy and Medieval philosophy. For Descartes to Kant and everyone else in the modern period, the imagination is a thing that structures things, it builds things in the mind, whereas opposed in the Middle Ages, imagination is a thing that perceives things and builds things but it also it’s also an organ of mental perception and that that door is closed after Kant, basically. Well in critical philosophy.

AP: I’m not sure how to respond to that because I think we go too deeply into philosophical terminology and it makes us lose the connection with Occultism, I feel.

JS: Yeah, we could jump back to thesis four and just pick back up where we were and try to go forward from there.

AP: Yeah, I was re-looking at the thesis. I think your summary is a good one and to me, what Adorno is saying, it is still quite biased I have to say. You know, when I reread the first three theses that we have gone through in the past couple of live streams, to me as I said, the first one tends to hint at the irrationality and the fact that occult beliefs and practices are, in a way, irrational and unscientific. And you link that with the Kantian idea of the importance of critical metaphysics. But I’m not sure he says it is a regression in consciousness and…

JS: Well, consciousness is very, very tightly circumscribed. Like he has a very specific definition of consciousness as he’s using. He doesn’t think it’s stupidity, he even doesn’t even think that they’re doing it on purpose. I think he refers to it as a reflex action.

AP: Also he talks about Occultism being decomposed monotheism and the fact that people turn to astrology because they don’t believe in God. So, I think that you’re summary is a good one. My perception is that it tends to make his arguments stronger than they actually are, to be fair. This is probably a compliment to you and not so much a compliment to him because it seems to me like you are summarizing and translating in philosophical terms, trying to find the roots, you know, the philosophical roots and the ideological roots of what he is saying in these theses.

JS: He goes off the rails and gives these anecdotes, right. Like he does those petty things that actually hurt him more than help him, I think.

AP: Yeah, but at the same time they are still informative about what his thesis is really about. I mean we shouldn’t just select what makes more sense to make his arguments stronger than it is.

AP: So, like for instance, I am looking at the thesis now. As I said I tend to move back and forth between your slides and the thesis and I reflect upon them. So, for instance, the second thesis starts by saying the second mythology is more untrue than the first. And the second mythology would be Occultism, which is a second mythology, second to religion, to monotheism. Monotheism is what he says. So he, in a way, let me see, it’s like to me he doesn’t really argue properly why that would be something that derives from monotheism. I mean, why is Occultism related to monotheism other than saying that since you don’t believe in God you believe in astrology and so…

JS: I think he thinks of it as a decomposed religion. I think he’s just conflating monotheism with religion because that’s true in the Western World in the 1940s, basically. I mean for 99.9% of the population. Like I’m fairly confident in the ‘40s there were more atheists than polytheists in the western world.

AP: Yeah, that makes sense.

JS: Like there are probably more bi-theists than polytheists. Like I think there are probably more Zoroastrians than there were polytheists in the 1940s. So I think he’s saying that because I think that was true in the 40s. Less true now but it’s still, I think, more atheists than polytheists.

AP: Yeah okay, I guess we can move on to the fourth one. As I said, my comment on your summarisation is that I think that it makes his theses stronger than they actually are. That is my personal take on that. No, I’m not saying that your summary is not correct and is not saying what he’s saying, I’m saying that I think it makes his arguments stronger because there are elements of these theses that make his argument weaker, I think.

JS: Yeah when it’s taking the good with the bad. But let’s start at four. Do you want to read or do you want me to read?

AP: You can read.

JS: All right, thesis four.

Occultism is a reflex-action to the subjectification of all meaning, the complement of reification. If, to the living, objective reality seems deaf as never before, they try to elicit meaning from it by saying abracadabra. Meaning is attributed indiscriminately to the next worse thing: the rationality of the real, no longer quite convincing, is replaced by hopping tables and rays from heaps of earth. The offal of the phenomenal world becomes, to sick consciousness, the mundus intelligibilis. It might almost be speculative truth, just as Kafka’s Odradek is almost an angel, and yet it is, in a positivity that excludes the medium of thought, only barbaric aberration alienated from itself, subjectivity mistaking itself for its object. The more consummate the inanity of what is fobbed off as ‘spirit’ – and in anything less spiritless the enlightened subject would at once recognise itself –

That’s a really good joke actually

“the more the meaning detected there, which in fact is not there at all, becomes an unconscious compulsive projection of a subject decomposing historically if not clinically. It would like to make the world resemble its own decay: therefore it has dealings with requisites and evil wishes. ‘The third one reads out of my hand. She wants to read my doom!’ In Occultism, the mind groans under its own spell like someone in a nightmare, whose torment grows with the feeling that he is dreaming yet cannot wake up.”

So again he’s really just dripping with…

AP: He’s really ranting.

JS: Yeah, I mean it’s just sarcasm at the top of his sarcasm turned up to 50. But there is an argument in here.

So that’s his argument I’m fairly confident, right. So I think it’s important to know that Occultism is a reflex action. That’s a really important idea, that it’s a response to something. It’s not…

AP: That’s his perception of Occultism.

JS: For sure, it’s a reflex action it’s born of a very particular kind of thing and it’s the case when it originates it is for a very particular kind of reason. And I think that again, “If to the living objective reality seems deaf as never before…” some good ableist language there unfortunately, “… they try to elicit meaning by saying abracadabra.” And I think the idea is that the world is, in fact, unresponsive to us, that’s modernity. Modernity is a world that is unresponsive to us. Pre-modernity is a world where we can make the world do things, we can pray and the world will change, we can do magic and the world will change. The modern perspective is there’s nothing you can do, the world is an immutable fact. You can manipulate it but you can’t fundamentally change it. And that is alienation, that’s classic alienation – that the world presents itself as something that is immutable to us. And what he says is there are a couple of responses to that, right. And for him it is very rational, the rational response to alienation is to seek out the real. When you feel alienated you don’t want to be alienated, it’s bad to be alienated, so you go find what’s really real. And I think what’s interesting is again, it’s that he thinks that the occultic response is ironic, that the fact that the world presents itself as alien and people want to connect to the real world.

This world does not appear to be real and people don’t like it and they try to do other things to get away from this world or whatever – the response is to seek out the real. And occultists do that, right. And so he thinks that this is basically an acknowledgement that the real is rational. But where they fail, according to him, is that they can’t accept the rational as real. This is the world and there’s nothing else, there is no other world. And for him, I think what he’s arguing here, is that rather than actually seeking out why the world is alienating the way that it is, the material conditions which give rise to the alienation they seek another world. But that’s just typical religion, right. If that were his critique it would be a typical critique of religion. But he thinks that the problem is that Occultism does something very unique because of how it regresses in a very hyper-modern context. And that regression in the hyper-modern context is that the world that they create, according to him, is filled with fetishes but fetishes that take the commodity form.

And this is an interesting defence of traditional religion and we’ll see this in a minute, is that traditional religion, because it’s connected to the pre-modern world,s a hedge against commodification but a new religion isn’t.

AP: But Occultism, generally speaking, is not new, we are not talking about a specific tradition here we are called talking about Occultism in general. And another problem that I see with Adorno’s understanding of Occultism is that he keeps referring to what occultists do, as something that has to do with another world, with a metaphysical world and there is an interaction with even the metaphysical world. But the concept that occultists have to deal with the supernatural is something that has been abandoned in the 20th century, from the 20th century onwards.

JS: Right. So we can use another word, we can use the word metaphysical entities.

AP: Yeah, but then it drops the argument against seeking a different world that is less real than this one. Because if it is actually, if the entities that occultists interact with are fully part of this world, they’re not supernatural, they’re not in another world. I mean it would drop the argument that they were even less real than this one is.

JS: World in the Husserlian sense? Not world in the sense of a different dimension but even the sense of world, even this world populated with metaphysical entities. So for instance, I don’t know, leprechauns or something or spirits or ghosts. So it doesn’t necessarily entail a separate world from this one or a natural or a distinction between supernatural and natural. It would simply be metaphysical entities of any kind. And I would say more than trivial metaphysical entities, we can bookmark qualia or something like that, that’s a different discussion but I would say things like spirits or ancestors or disembodied intelligences, things like that, which could completely exist in this world. But the idea that, for instance, one could go consult the akashic record, which could be something that exists in the world but it he would think that it would be a metaphysically empty category or an ontologically empty category. So I use world there in the Husserlian sense.

But it’s the fourth point that I think is the most critical for him, right. It’s a problem born of alienation that’s unique to religion, that’s just classic historical materialism. But it’s because it emerges in this very particular modern context and in a very particular period in late capitalism, then it’s more imbued or distorted, you might say, or metaphysically, I don’t know what the right word, is corrupted or whatever, because of when it emerges it emerges under the aegis of commodity fetishism and therefore it reproduces the least real elements of this world. And so occultists have a dual problem; the conditions that gave rise to alienation are still here, they’re still out there in the world, like the market, you know, fascism, whatever. But also, now they have to diminish themselves with beings that don’t exist; like the ancestors or Enochian spirits or fairies or changelings or gods. So the problem redoubles upon them actually. Like I think what he’s saying here is it makes the situation worse and now we have a negative feedback loop.

AP: I guess that I can see his point but it’s just that the premise is not something that can be proven really. There is so much in it that sometimes I get a bit lost and I have to reread it.

JS: Yeah, he’s not helping us at all. That’s why I redid all these theses because he’s such a… But I think that last line, right, “in Occultism the mind groans under its own spell like someone in a nightmare.” It’s that phrase, right, it groans under its own spell, it’s for him, the occultists are tormenting themselves by thinking that… and we’ll get to astrology in a minute, by trying to think that astrology is determining your life or that spirits are telling you what to do. It’s already bad enough you have a boss, like that’s you know that’s bad enough. But now you have a metaphysical boss that you invented.

AP: Yeah but this problem is that you know, that’s his perception that they invented it. But for occultists, that’s not the case. It’s not something that they invented. So he is, in a way, arguing against Occultism, not from the point of view of those who believe in Occultism but from the point of view of somebody who has his own idea of Occultism, as somebody outside of Occultism that knows very little about Occultism. Probably only what he reads in the magazines of the time.

JS: I think that was a good bit. I mean I think he knows something about Theosophy, we’ll see that in a minute. I think he knows a bit more than we’re giving him credit for. At least again, what he knows in the ‘40s, what’s knowable in the ‘40s. So I think he knows something, but again we could just sub out the word occultists and just put any kind of philosophical point of view that does this. He’s just having to pick on a particular kind of… he’s just using the word Occultism but you know you could basically pick anyone who violates Occam’s razor and makes the violations of Occam’s razor interact with them in negative ways or any way at all.

But this would also be true of this would be true of religion in a general way but he thinks that there’s a particular way it’s true in Occultism, in a particular way that it’s true because of the situation in which it emerges. Which would not have been true for, I don’t know, John Dee. But John Dee had his own problems, like you know, the spirit world of that world is reconstituted along feudal lines, which is in some ways even worse.

AP: I don’t know. I guess, for me, it’s kind of difficult to argue against it in detail because I just think that the premise is not correct. So when we got into his argument I think that in the details of his argument, I find it more difficult to respond in any way because I find it so difficult to agree with the premise to begin with.

JS: Yeah, that goes back to thesis one, right, that basically if you don’t accept all three parts of it then none of this is going to work for you. That’s why I think it’s interesting that anyone would read this, like aside from people… or that’s not true. That’s also why I think it’s interesting that if you don’t accept these positions basically the rest doesn’t follow. But that’s just how philosophers work, I mean they operate from axioms and theorems and propositions. We can call it a bias or we can call it a philosophical position but I think it’s less a bias and more a position, it’s just a position that I think Angela you don’t agree with and probably very few people in the chat do either. Hence me losing subscribers, which is interesting because people love the idea.

AP: Have you really lost subscribers?

JS: Oh, yeah. I’ve lost like three dozen subscribers since we started doing this. You can see every episode that I look at or how many subscribers you get or lose and each one, every time I do this I lose like somewhere between 12 and 20. People like rage quit which is funny because it’s just proved to me that there are a lot of people who like everyone says they don’t want to live in an echo chamber and then when there actually is a thing that really deeply questions what they believe they rage quit. They unsubscribe, they’re like I don’t want to do this.

AP: That is too bad.

JS: Yeah, I think it’s like grist for the mill. Like, oh yeah, we don’t want to be challenged and that’s part of the reason why I wanted to do this, this essay because it is, especially for left-wing occultists, if you’re like a right-wing occultist right then you can just go full-blown tradition you could be a hardcore you know sort of Evolian, Guénite kind of traditionalist and then you can just reject everything because this is just Marxist garbage for you. But what’s for me, I think that there are very few of those people, I think, in this. But I think here we have a huge combination of people who are both left-wing and occultists and what Adorno’s saying is you can’t do both. And if by left-wing you mean sort of in the Marxist world of the left-wing, like in the related historical materialism which is interesting because that’s the methodology I use on the channel. Esoterica is a historical materialist channel.

AP: Well, as you know, I’m not a historical materialist. I can use historical materialism. Yeah, I do that in some of my scripts but my scripts and my videos are based on peer-reviewed sources. So when the scholar has used historical materialism that will be the methodological angle and one that is not the case, then it will not be the case. So it also depends on what the angle of the papers that I’ve selected has taken.

JS: Have you come across any papers from people who are historical materialists?

AP: Hanegraaff.

JS: No, Hanegraaff, he’s a historicist but I think he’s sort of a classic positivist historian. He’s definitely not a Marxist. I think he’s just a good old-fashioned as you know – how it really was.

AP: I do know Marxists who are in academia but I don’t think that they use historical materialism in their research. There’s an Italian colleague of mine, who also works on contemporary occult practices and uses anthropological methodologies. I don’t know, do you think that you can be a historical materialist and an anthropologist at the same time?

JS: Oh yeah…

[Dr Sledge searches for book and author]

…But yeah, “The Rise of Anthropological Theory” is that the big book. Yeah, Marvin Harris and the 1968 The Rise of Anthropological Theory basically developed and then he developed it further in “Cultural Materialism”. Oh yeah, there are definitely folks out there doing that work.

AP: Yeah then I’m not sure. Are you familiar with any academics who are historical materialists and work on esotericism, I mean?

JS: No. Basically none.

AP: Do you think that that’s because it’s not a viable methodology for studying esotericism?

JS: I think it’s because 75% of people working on Western esotericism are esotericists.

AP: No, I don’t think that’s true.

JS: I mean I would say that there is a significant plurality and if you believe that you’re definitely not going to be doing historical materialism you cannot be a historical materialist and be believing in, you know, Enochian spirits or whatever. So no, I think that I think it’s unique – there are historical materialists who work in religion – but I think that it’s unique. It’s the public secret of Western esotericism studies that a significant chunk of its scholars are in the broom closet and so, in that case, that’s unsurprising here. You’re going to see very few historical materialists. I would be willing to argue I’m probably the only one.

AP: May I suggest that perhaps historical materialism might not be the best way to understand Western esotericism and that’s why it’s not used as much?

JS: It could be…

AP You know that I think that historical materialism is, what’s the term? The dirty words that you called it last time. Not an oversimplification but a reductionist. Yeah, it is a reductionist approach and I think that in order to understand esotericism applying a reductionist approach is probably the least useful way to approach, to understand esotericism and I don’t think that has to do with whether you are an esotericist or not it is just looking at what esotericism is. I guess that as a historical materialist, it could be more useful to understand the effect perhaps or the material causes and effects of esotericism.

JS: That’s all I do. I mean and it also makes me, as a historical materialist, I’m agnostic about the claims made by occultists or by historical occultists. I don’t think they’re true but I don’t really care. For me it’s about doing history, not about diagnosing their faults or if I believe Aggripa is wrong about his metaphysics then that’s a philosophical argument I can have with him but I’m doing history, I’m just doing history. But it’s history grounded and why would Agrippa be writing this at this time etc.? Why is he prosecuted, why is he not prosecuted while all the women were? You know so but no I think historical materialism is actually very powerful precisely because of its reductionism and again I’m very pro. I’m a proud reductionist. I don’t know if this is the like we said before it’s one of these really weird dirty words that I know people just like in religious studies. I remember being in religious studies in graduate school and undergraduate people just like that’s reductionistic and I’m like, yeah that’s a compliment for me.

Reductionism is the most successful theory in the history of theories, basically.

AP: Well yeah, of course, if you narrow it down to almost nothing or something so small then you can feel comfortable that you got it right but you still haven’t got the full picture.

[Laughs]

JS: I think that as far as academic methodologies go that I mean it definitely means that we remain within the world of the world.

AP: Physicality, not the world. You see, you’re being reductionist even in the way you explain historical materialism.

JS: Yeah.

AP: You’re saying we are just sticking with the reality of the world but these are statements that are very reductionist because what is reality? And what is the world? If you are defining reality only by the things that you can measure and see with your five senses or not even that, I think because you are not a phenomenologist. So it’s even more reductionist than that.

JS: Yeah, we don’t play ball with the phenomenologists either. I mean again but that’s what… I mean could you get a peer-reviewed paper with unverified personal gnosis, as I saw it, I heard it, I heard it in a dream?

AP Well if you study anthropologically… I actually, don’t know if it’s gonna get accepted but I proposed the paper at the American Academy of Religion on understanding the concepts of unverified personal gnosis and verified personal gnosis. Obviously, as an anthropologist I don’t try to prove whether it’s right or wrong, I’m just trying to understand how people articulate that and how that creates meaning in their life and how it’s reshaping practice and all of that stuff.

JS: But you couldn’t submit a paper that was your own like you had a vision.

AP: My own? No.

JS: Yeah, that’s what I’m saying. Like it’s just that’s this academic rigour it’s not…

AP: But academic rigour is not, I wouldn’t argue, that it is reductionist. I think that first of all the methods that we use in academia change all the time, depending on what allows us to get the most accurate knowledge at a given time and that changes all the time. And it changes also because, and that is in my opinion because knowledge is a moving target. So I’m the opposite of a historical materialist because I think that even what we have in front of us changes all the time.

JS: So that could be true but it would still be the case that if you want to publish a paper then there have to be evidentiary standards and it just happens to be that and those evidentiary standards are very much in agreement, I think, with historical materialist methods. And again, for me on the channel like I’m doing a 45-minute deep dive into a fourth-century gnostic text. I don’t have to believe it’s true but I have to understand it and you know, and I don’t have to like pass judgment on it, at least as a scholar. Now someone asked me philosophically, do I believe that these are handbooks for how to get to eternity, I would say no, I don’t believe that, there’s no evidence for that. But in terms of producing knowledge, yeah, that’s why I think that’s why you wouldn’t even know that there is a methodological position at work in my content creation.

AP: Yeah, I agree with that and also on the matter of the fact that there are many or any, I don’t know, and now I’m curious to know whether there are scholars in esotericism that use historical materialism. But even though it might be, I would suggest – obviously you don’t agree, that the reason is that perhaps that’s not the most useful methodology to understand esotericism. But I would still argue for having a historical materialist approach and study of esotericism just because I think the more perspectives and the more methodological perspectives we can have the better. Exactly because I’m not a reductionist and so I want to see all the methodologies applied and I want to see all the results from all of that.

JS: Yeah, I’m fine with that. I don’t, I mean let a thousand flowers blossom.

AP: So I’m not against using historical materialism but I wouldn’t just stick with that and not experiment with other ways of looking at things.

JS: Yeah, I’m happy to read papers from phenomenologists. I mean they’re tiresome but I’ll read them. I had to take whole seminars on phenomenology which were very tiresome but yeah I’m perfectly happy if someone wants to take a phenomenological approach. I’m like sure, great. I mean it makes for long books when you pick up the Heideggerian approaches like Elliot Wolfson and write these long-ass books on Kabbalah I’m like man it’s good for academics to take a Heideggerian perspective it makes your book six times longer than they might be otherwise so that’s good. Also, some folks are saying that reductionism and the study of dynamic systems theory and emergent behaviour that’s very much like if you read Plekhanov? Plekhanov basically predicted, and described what we now refer to as emergent behaviour in the 1920s. So it’s completely compatible with theories of reductionism. I mean again because things have to emerge out of something. Emergentism is not a disproof of reductionism, it is proof of reductionism because emergentism means that things have to emerge from something. Simply because two water molecules have the property of being wet while one of them can’t that the emergence of wetness is emerging from something specifically water molecules. So, yeah I don’t know why that’s often thought of as like dynamic system series of rebuttals against reductionism and materialism but…

AP: I don’t know enough about emergent behaviour but I’d love to have my Patron Dave here now because he works on that in AI and for his job and about emergent behaviour and the new research. So I don’t know enough about it to argue whether it is in line with historical materialism or not. But what you’re saying makes sense in terms of emergence is, in a way, very materialistic. The way it is, in my understanding, the way it is conceived is not like the development of consciousness, at least that’s my understanding. But as I said I had limited knowledge about it.

JS: Right. And also I find that a lot of people when they use terms like emergentism are just waving their hands because they don’t know what… It’s just we don’t know why it does that and so I’m very, very slow to say something is emergent as opposed to being like, yeah that has properties that we don’t know. Also when people say that things like wetness are an emergent property I’m like well, I’m pretty sure that’s like classic category error wetness is an adjective that doesn’t actually correspond to an actual condition, I don’t know, I think that’s like a failure medieval philosophy.

But can we do thesis five before we wrap up?

AP: Okay.

JS: All right do you want to read it? I can watch your blood pressure go up as you read.

AP: Well that would be good because I suffer from low blood pressure. So…

JS: Oh that would help you. Yeah, so you just need to read more Adorno.

[Laughter]

AP: Yes.

JS: I had low blood pressure and then I read Adorno every day for the rest of my life and I’m fine now.

AP: Yes. So let’s be Zen about this, Angela. You can do this.

The power of Occultism, as of Fascism, to which it is connected by thought patterns of the ilk of anti-Semitism, is not only pathic.

What does pathic mean?

JS: I think he means not only pathic in a sense of pathological, not pathic in the sense of emotional I think pathic in the sense of like pathic like in sociopathic like in the bad sense.

AP: I thought that my version was… I had a typo to be fair but I wasn’t familiar with the term anyway.

Rather, it lies in the fact that in the lesser panaceas, as in superimposed pictures, consciousness famished for truth imagines it is grasping a dimly present knowledge diligently denied to it by official progress in all its forms. It is the knowledge that society, by virtually excluding the possibility of spontaneous change, is gravitating towards total catastrophe. The real absurdity is reproduced in the astrological hocus-pocus,

That is always kind of him to insult while he’s trying to be clever and not succeeding.

Well, who says that? That’s not an argument that some people that believe in astrology would endorse.

… as knowledge about the subject. The menace deciphered in the constellations resembles the historical threat that propagates itself precisely through unconsciousness, absence of subjects. That all are prospective victims of a whole made up solely of themselves, they can make bearable only by transferring that whole to something similar but external. In the woeful idiocy they practice, their empty horror, they are able to vent their impracticable woe, their crass fear of death, and yet continue to repress it, as they must if they wish to go on living. The break in the line of life that indicates a lurking cancer is a fraud only in the place where it purports to be found, the individual’s hand; where they refrain from diagnosis, in the collective, it would be correct. Occultists rightly feel drawn towards childishly monstrous scientific fantasies.

That’s nice.

The confusion they sow between their emanations and the isotopes of uranium is ultimate clarity. The mystical rays are modest anticipations of technical ones. Superstition is knowledge, because it sees together the ciphers of destruction scattered on the social surface; it is folly because in all its death-wish it still clings to illusions: expecting from the transfigured shape of society misplaced in the skies an answer that only a study of real society can give.

JS: I got you to read that one because you have your recent episode on astrology. Yeah, he picks on astrology here.

AP: Have you watched it?

JS: I have watched it briefly. Yeah, I watched it like I need to go back and re-watch it. Thursday nights are my watch all my YouTube people nights. So tonight I’ll work through it.

AP: Yeah and I’m sorry if I was reading it slowly but it is partly because I find it hard to read, you know, and partly because I have to keep my screen at a very bizarre angle to be seen the way people see me and so it’s a bit more difficult to read things because of that.

JS: Also you’re reading in, you know like you’re obviously… people forget sometimes that English is a second language for you and Adorno’s English is incredibly hard. So like I’m again I always just like so impressed by anyone who’s like – it’s for us Americans who are all monolingual people or most of us are like when people work in a second language and they work on something that’s impenetrable like damn Adorno. It’s always super impressive to me.

AP: Thank you.

JS: And it’s clear, it’s clear in the German but that’s such a, what’s the right word, such a pompous thing to say but it is clear I’ve been in the German.

All right, so I can try to unpack this and see what I think his argument is but I think his argument goes like this: so we’ve diagnosed, right, what he thinks is going on here that is to say the subjective pre-critical metaphysics is born of alienation. But he’s arguing that because it’s born of alienation in the specific case of late capitalism that it produces thoughtforms that are specifically conspiratorial in nature, which is to say, the commodity strikes us as alien and therefore frightening and bad because it is frightening and bad. And when we project it into a hyper-reality, another reality or however, we want a supernatural world or a metaphysical World it also frightens us, it also strikes us as negative and therefore that develops a conspiratorial kind of thought form, fundamentally. And what he links right here is Fascism and we’ll come back to that in a minute because he thinks that again the regression and thought he’s thinking of here is fascism, of which Occultism he thinks is a particular symptom.

And so his argument is that when the world strikes us as alien and when these other entities strike us as alien or foreign to us, this inverts social causal mechanisms. That is to say, there’s an ironic move where things that actually have no power over us whatsoever, spirits or ancestors or stars or whatever tradition for that matter, that when we do that right when we have these kinds of ideas that things that have no impact on us whatsoever, like stars or ancestors of spirit, the inversion is that that makes us not believe that the things that do actually have an impact on us, do. Which is, of course, for him the social forces and organisations of production. So this inverts reality for him, that the stars which are completely alien to us and have no effect on us now have a huge effect on us even despite the fact they don’t and what really has an effect on us like the stock market, which again is completely unreal, get ignored. I think I’ve said this before, that a single shareholder can flex and blink and do more damage than every Enochian spirit combined.

My double dog dare, the Enochian spirit to do more damage than Elon Musk. I think he’s more powerful, he has more power in his pinky, in a Tweet than all the spirits combined. And what he notices about that is and I think this is really interesting and I think he’s not wrong about this, is that this because Occultism has this particular trait it generates a co-morbidity and that co-morbidity is a conspiracy theory. And one of the things that’s interesting right that one of the things that Fascism and Occultism share is a unique history of anti-Semitism. Like a shared history, a deep shared history of anti-Semitism. Whether it’s Theosophy or else for Crowley or like Christian Mysticism, it is shocking how almost all of them share some degree of anti-Semitism and that’s what Fascism also shares with it. And so that link is not because it just sounds…

AP: Is it something that pertains to Occultism or was it just a moment in history? Because at the moment Occultism is very much left-leaning. Of course, there are occultists that are more right-wing but, for instance, Paganism is for the most part quite left-leaning and not anti-Semitic, I wouldn’t say.

JS: So there are certainly exceptions but I would say organised Occultism in the 20th century was significantly influenced unfortunately by anti-Semitism like through Theosophy…

AP: Yeah, but I guess my question… yeah, I agree with you, I totally agree with you with that. I guess that my question is, is there a feature of Occultism or is it because Occultism at that specific time was influenced by that specific time period and the Zeitgeist?

JS: I think yeah, I think he thinks it’s not unique to Occultism but Occultism suffers from it specifically, for instance, also I think that anti-Semitism is just a general version of conspiracy theory and it is to me interesting how often Occultism and the conspiracy-theory world overlap. And that’s grist for his mill that they’re born of a shared irrationalism. Like the amount of occulty people during Covid who were anti-vaxxers, the anti-vax movement in the end…

AP: There was a specific type of occultist or like the Theosophists would be, you know, within that camp. But I think that the problem is that you’re lumping together so many different traditions in one category and that is not the case. I agree with you that there is part of Occultism that can overlap with conspiracy theories but there’s also a huge chunk of what can be considered Occultism that doesn’t at all, like in the slightest and in fact, they tend to be very influenced and interested in academic research and science.

JS: Sure and so it’s, I think, he would say it is the exception that proves the rule like I don’t know…

AP: It’s a big exception, you know, it’s a big exception, for people to see it as an exception.

JS: I mean I’d be curious to know what, among occultists and the New Age movement because the New Age movement is shockingly penetrated with all kinds of conspiracy theory stuff, like if you take that movement and compare it as a percent of the population and a mainstream religion like Catholicism and see what percent of Catholicism or Judaism or whatever, what percent of those people subscribe to conspiracy theories and then check the same thing on Occultism and see what percent of the religion subscribes to them. I think I would take the Pepsi Challenge and argue that in the occult milieu, in which I would group The New Age movement, Paganism, neopaganism, you know, Kabbalah, all that stuff – I would be willing to argue and I would put as a supposition, it’d be interesting to check, that I’d bet those conspiracy theories are more of a problem in those circles than in the mainstream.

AP: So, okay I can answer that to an extent. I interviewed on my channel David Robertson, who has worked and published on conspiracy theories and so if people are interested they can look at that interview because I asked specifically about that. And what emerged in his research, in relation to Paganism and belief in magic, and even though there seemed to be people that hold both beliefs but there are also people from all walks of life or religious life that are conspiracy theorists. And anecdotally looking, for instance, at the Italian context and what happened during Covid. There were a huge number of Catholics that were conspiracy theorists, you know, even from my home city and other neighbouring cities in southern Italy, there were so many Catholics that were conspiracy theorists.

So think that for instance during Covid, personally don’t I don’t think so but obviously, we would need a sociological study to verify that. I would be interested in interviewing Joanna Parmigiani at Harvard University because I know that she has worked recently and published on conspirituality. So that that would be interesting to investigate you know when spirituality and conspiracy theories go together. But I think that to assume or to imply that within the occult milieu, you have a higher percentage of conspiracy theories that, I don’t think that that’s true, but yeah, I don’t have data to back that up but my perception is that that is not true because the I’ve you know my experience with occultists have ranged from Thelema to Paganism. For instance, within the Pagan Community, you won’t find many conspiracy theories you find more of those within the New Age movement, for instance, Theosophy, Anthroposophy, and Christian Mystics also, I would say they are more inclined towards conspiracy theories than Pagans, Thelemites and other causes are. That is my anecdotal perception. So obviously we would need sociological.

JS: Yeah, we need data. I guess I have the opposite suspicion. I think it would tick higher and I think it would tick higher for a reason similar to what he’s saying, which is that people become occultists primarily out of alienation. That’s his argument, that they become alienated from, for instance, a traditional religion they grew up in and they go looking for the truth, whatever the truth is. And they subscribe to occult beliefs in the part of that. I think that suspicion actually he thinks that’s actually a very healthy thing, right. Like that’s the reaction, the reflex reaction that he thinks is correct, that the response the actual rational response to alienation is to go looking for what’s really real. He thinks the argument though, that the problem is that they don’t find what’s really real they end up creating an alternate reality that isn’t real at all. It’s worse in some ways. But his argument is that the very impulse also is co-morbid with the kind of irrationalities that give rise to fascism, which is basically a conspiracy theory, and anti-Semitism is basically a conspiracy theory.

And in the second thing, the last thing he says is that because Occultism is for him fundamentally a subjective thought form, which is to say it’s about what individual people think, not what is true objectively, right. It’s about subjective truth and subjective experiences and because it’s so focused on the subjective that the objective basically has to come to serve the objective(?). And that means pseudoscience runs wild too, that’s the last thing he says, right. That whole business about monsters at scientific fantasies that they see emanation for the isotopes of uranium and blah blah blah, that for him, he just says that pre-modern religion had a dialectical relationship between subject and object.

Enlightenment relations were subject-object domination for him given liberalism and late capitalism in which were all individual consumers and individual people with individual rights, the subject dominates the object and the object must serve the subject. And therefore you get all these, like for him he thinks it, I think he results in widespread pseudoscience. And like I will say, at least for my channel, the amount of pseudoscience that I have to delete off my channel, boggles my mind. Like the number of people that believe that quantum theory proves something about their metaphysical beliefs is… like boggles my mind. Like, that I hear that stuff constantly and that, you know, that I think that is an aspect that does trouble me deeply. Where like objective truth, and scientific truth, so we’ve now firmly, quantum theory is the most it’s almost empirically verified theory in the history of the world and has to serve – comes to serve nonsense metaphysical beliefs. As if spooky action at a distance proves magic or something which there’s no reason to believe. That it’s not even… there’s no reason to believe spooky action at a distance is even happening. We can totally take a Bohmian analysis of that we don’t really need to have spooky action at a distance.

But that’s the last argument, the last part of this argument is that it results in conspiratorial thinking, which is dangerous and it results in pseudoscience which is also dangerous.

AP: I would argue, I would say that that is possible that it can lead to those things but I don’t think that it is something that is specific to Occultism. So maybe when in my case when I agree with Adorno and the critiques that he moves to Occultism, the specific critiques that I agree with, I don’t think that they are specific to Occultism. I think that there are many other cultural phenomena that can produce the same effect and I don’t find it to be something that is peculiar and specific to Occultism. It can be found in Occultism but it can be found in other cultural and religious phenomena as well.

JS: That’s definitely true but I think that he’s at least saying it’s uniquely bad here and maybe he’s even saying that when you find it elsewhere it’s actually just another form of Occultism out there. So that’s just what he’s defining it for right or wrong. But I think now we’re buried in whatever, number five, this is what he’s cashing out of it. I think this is his real worry, that Occultism and Fascism share in common irrationalism, a very modern irrationalism and two of the results of it are conspiratorial thinking – which anti-Semitism, of course, is a form of that. And of course, most Fascisms use some form of conspiratorial thinking. Whether it’s the immigrants, the Jews or the Freemasons or something.

AP: I think that there are many political views that use conspiratorial thinking or populist thinking.

JS: For sure and populist thinking is just on the road to Fascism usually anyway. Just typically they’re just fascists in disguise or they just don’t know they are until you know they get power and do what they want.

AP: Yeah I guess I was thinking about Brexit too, you know, that was also conspiratorial and in the way, it was formulated and presented and people who, for the most part, were not occultists still voted it.

JS: So right so, as his argument is not that all conspiratorial thinking is related to Occultism but rather Occultism uniquely suffers from this, it uniquely suffers from this trifecta.

AP: I disagree but I can see why you would think that in the 1940s. Because in the 1940s you have some quite prevalent occultists that were fascists.

JS: I mean which ones weren’t? Like which ones weren’t basically Nazis, I mean from Aleister Crowley to the Theosophical Society too, you know, I mean esoteric Hitlerism.

AP: Yeah, I think that it makes sense for him to think that. I don’t think it is true now but it makes sense that he would think that at that specific time in history. But as I said I don’t think even in that case I think that Occultism has its own unique traits but it is also part of the historical time and the cultural time that is going on at any given time. So I would say that, for instance, today Occultism tends to be… of course, there is there are also right-wing people within Occultism but for the most part I would say that it tends to, it skews more left and right, for instance.

JS: Certainly Paganism does, I would say.

AP: Paganism does definitely but I think, you know, even in Heathenry that is often seen as more right-wing but there are so many left-leaning people in Heathenry they are trying to defend them against Volkism and volkish type of Heathens. So, I don’t know, that would be another interesting sociological study to do the political… but from what I’ve seen in Italy and what I’ve seen in the UK – my experience and this is anecdotal as well because we don’t have sociological data but most people within the occult community are left-wing now but I wouldn’t be surprised if in the 1940s it was the opposite. And that is because, to an extent probably to a considerable extent, Occultism is also a product of its time. So at any given time in history, it will be influenced by what’s going on in the world.

JS: And that’s coming dangerously close to historical materialism.

AP: But I’m not the reductionist. So I don’t exclude that perspective, I include it in something wider that also encompasses more than the historical materialist perspective.

JS: Okay do you want to do the sixth one, the sixth one’s easy. This is the easiest one of all of them. I know we’re at an hour and a half but if we do the sixth one then we just have like one more session I think and we’ll wrap this up. I can read it quickly and it’ll be easy to do.

AP: Okay, then you can read it.

JS: All right, last one.

Occultism is the metaphysic of dunces.

This is really a slander against Duns Scotus, people.

mediocrity of the mediums is no more accidental than the apocryphal triviality of the revelations. Since the early days of spiritualism, the beyond has conveyed nothing more significant than the dead grandmother’s greetings and the prophecy of an immanent journey. The excuse that the world of spirits can convey no more to poor human reason than the latter can take in, is equally absurd, an auxiliary hypothesis of the paranoiac system; the lumen naturale (the light of reason) has, after all, taken us somewhat further than the journey to grandmother, and if the spirits do not wish to acknowledge this, they are ill-mannered hobgoblins with whom it is better to break off all dealings. The platitudinously natural content of the supernatural message betrays its untruth. In pursuing yonder what they have lost, they encounter only the nothing they have. In order not to lose touch with the everyday dreariness in which, as irremediable realists, they are at home, they adapt the meaning they revel in to the meaninglessness they flee. The worthless magic is nothing other than the worthless existence it lights up. This is what makes the prosaic so cosy. Facts which differ from what is the case only by not being facts are trumped up as a fourth dimension. Their non-being alone is their qualitas occulta [hidden quality]. They supply simpletons with a world outlook. With their blunt, drastic answers to every question, the astrologists and spiritualists do not so much solve problems as remove them by crude premisses from all possibility of solution. Their sublime realm, conceived as analogous to space, no more needs to be thought than chairs and flower-vases. It thus reinforces conformism. Nothing better pleases what is there than that being there should, as such, be meaning.

All right. So there’s not much going on in this one actually frankly he’s just spewing invective most of the time. In his argument, I think is the…

AP: And then you wonder why people hate him.

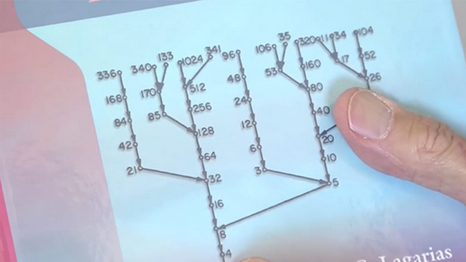

JS Yeah, I know. I never wondered why people hate him but I just wonder why people disagree with him. That’s very different. His argument here right is that basically, despite the claims of occult knowledge, right, speaking to ghosts or spirits or gods or whatever, Occultists claimed to have access to – capital-T-truths, right. Whether it’s the akashic record or whatever. But yet for more than a century, they have not produced anything other, in his opinion, than platitudes. Unverifiable claims or just nonsense masquerading as spiritual philosophical depth. So basically what he’s saying is Occultists claim to have access to a world of fundamental truth and yet have produced nothing. They produce nothing in terms of anything other than platitudes. Like everything is one or something and this is what I sometimes call my Enochian Collatz conjecture threshold.

Sometimes people will tell me things like, yeah, I talked to the Enochian spirits and I’m like. Okay, that’s fantastic. Or I’ve scried the Aethyrs, I’m like that’s great scry the Aethyrs. And they’re like, well the Enochian spirits tell me stuff, why don’t you believe me? It’s like I don’t disbelieve that they’re telling you things, you might believe you might be experiencing that. But if you want to get my attention give me an Enochian spirit to solve the collapse conjecture, that’s my threshold. Like if a spirit or an ancestor or a God just solves the Collatz conjecture, gives us a proof for the Collatz conjecture, if they do that you’ve crossed my threshold and now I’m listening. You have my undivided attention but until then you don’t have my undivided attention and so his argument is that it’s produced no truths about the objective world whatsoever. And rather it generates data which does more to reflect the subjective conditions of the creators more than anything else.

So we learn more about Theosophists from them telling us what’s in the akashic record then we learn about what’s in the actual akashic record. So and then again the comeback here, of course, would be, oh it produces meaning or happiness or enjoyment or I get meaning out of it or you know I have experiences of spirits talking to me and of course, what Adorno going to say is, no. Because the very underlying conditions which are giving rise to this are ideological and so, at the fundamental level, you’re going to repeat back the ideological thought forms that give rise to the world of the spirits that are talking to you in the first place. So his argument is that for, you know, for more than a century I guess in his mind he’s just saying for more than a century we’ve had thousands of people talking to these things and they’ve not produced a single piece of objectively real information and what they have produces platitudes or experiences but again those are again unverified personal gnosis.

AP: Well, on that I have my ideas, obviously. So in a way, I agree and in a way, I disagree because and probably there are colleagues that would disagree with me now with that because there are scholars in Esotericism even now currently that want to actually prove the fact that magic has an objective effect on reality. I tend to be a bit sceptical about that just because my impression is that magic works in a way that is different from how the physical world works and it tends to move more through acausal connections as opposed to causal connections. The fact that whether magic causes objective changes in reality or not, well this is not something that I have data to say that it is correct.

I can say that many practitioners report that as a result of magic workings things will change. The thing is that magic works in ways that are very different from how the physical world works. You will still get changes in the physical world but they will happen in ways that are sometimes unexpected so when you do a successful magic ritual as practitioners report, you will get the desired effect but you cannot control how it will happen, it will happen but you cannot control how. So that is why it eludes the scientific method as it is now, although as I said there are scholars currently that are trying to you know create – they are working on doing experiments in that respect. So we’re gonna see in the next few years what happens. Maybe I will be proven wrong in that but my perception is that magic works acausally and in a way that is not the same as how the physical world works and that practitioners report that it is effective.

So when we talk about objective changes in reality, again if we start from Adorno’s premises I can understand his argument but for instance, I don’t think that there is an objective reality. So I think that there is an inter-subjective reality which is different even though it can be probably it’s the closest thing to objectivity that we can get without the absolutism that objectivity brings about and brings to the table. So since I don’t believe in the concept of objectivity then this claim that magic is not real because it doesn’t produce objective results, for me, it’s not an argument that stands because then you have to prove to me that reality is objective, to begin with, and that is not something that you can prove either I don’t think. You know, nobody can prove to me that I exist, for instance. The things that you can prove are still within a very specific set of premises even when we talk about how natural scientific methods work, they are still working within a specific paradigm.

JS: So I guess the question would be using any paradigm you would want, what would be an experiment that would disprove the existence of the ability of magic to do things causally?

AP: So you mean that magic then follows the laws of cause and effect that we have in the physical world?

JS: Or any theory of cause and effect. Like I’m not frankly sure of what acausal means. Because that just means not causing something. But that can’t be what it means. But I mean, yeah…

AP: It is something that I briefly talk about in my latest video on astrology and Wolfgang Pauli and Jung. So when we see the physical world and we try to understand the physical world, one of the foundational elements of how we understand the physical world and even through some natural science is by cause and effect. So for instance, the famous tenet in Natural Sciences correlation is not causation when two things happen at the same time it doesn’t mean that one has caused the other. So one of the aims of Natural Science, in most cases, is to find the cause, not just the correlations. Whereas in magic and this is something that you find in Jung and you find in Pauli and you also have the possibility that there are things that happen in an acausal manner. This means that they happen simultaneously and they are not linked by cause and effect they are linked by meaning. So meaning is what links them together and allows them to occur at the same time. So you still have a co-occurrence of things that can happen over and over they’re just not linked by cause and effect.