Dr. Angela Puca: Hello, Symposiast. I’m Dr. Angela Puca, a Religious Studies PhD. As you know, this is your online resource—now live stream—for the academic study of magic, esotericism, paganism, shamanism, and all things occult. As you know, part of my project is bridging the gap between academia and the community of practitioners. To do so, I would like to have both academics and practitioners on my channel. Today, I have the pleasure of having a practitioner, so we will have a more practitioner-oriented type of conversation today. But before I introduce our fantastic guest today, I would like to remind you that Angela’s Symposium is a crowdfunded project. So this exists, thanks to you guys. If you want to keep this project alive and ongoing, I would appreciate it if you consider supporting my work with a one-off donation. There’s PayPal and KoFi, and there are monthly memberships that you can get on Patreon. You’ll find all the links in the info box and in a pinned comment, although YouTube is going to take away the clickable links. So, rely on the bio because the clickable links will remain there. So, thank you all for considering supporting my work, and thanks to all who have supported me. Now, let’s bring in our guest. I’m very, very pleased to have you here, Benebell. Is Benebell “Wen” the right way of pronouncing your surname, by the way?

Benebell Wen: Absolutely, Benebell Wen is perfectly correct. Hi, Dr. Puca.

Angela Puca: Yeah, thank you so much for being on the show. I read your book, and it’s—yeah, I would really recommend people to get it. You guys will find all the information about Benebell in the info box as well, so don’t forget to check it out. So, first of all, Benebell, thank you for being here on Angela’s Symposium. How are you today?

Benebell Wen: I’m doing well; I am very excited to be with you. So I’m doing fantastic, actually.

Angela Puca: So, apparently, you knew of my work?

Benebell Wen: Who doesn’t?

Angela Puca: Thank you. I know of your YouTube channel as well. I think it’s quite informative for people who want to know about Taoism, tarot, and I Ching, of course, which is going to be the topic of today’s conversation. And on that note, how would you describe I Ching for, you know, to somebody who has no prior knowledge of it?

Benebell Wen: I love that you pronounced it correctly. It is “Yi Jing,” but I say “I Ching” because when I speak English, I notice if I say “Yi Jing,” I lose some people. I say, “I Ching,” everyone’s on board. So, I’ll just continue saying “I Ching,” but you are actually saying it correctly, so I love that.

Angela Puca: Yeah, we had a conversation before going live where I was explaining that I come from a background where I studied Eastern Asian traditions and languages. But yeah, please go on.

Benebell Wen: Okay, so the I Ching, I would describe it as a sacred text because “Jing” means “sacred text.” It’s written in a binary code system, so it’s written in binary code. That’s what the I Ching is. That forms eight trigrams, and then through—I would say—permutation and calculus, calculus being the mathematics of change, it forms six-line bits of diagrams that we refer to as hexagrams. So the eight, through permutation and calculus, becomes 64 hexagrams, and these 64 hexagrams represent a cycle and a circle of change and also represent the 64 laws or codes and axioms of life. And so we also consider the little text that comes, you know, the text in classical Chinese that gets translated into English that’s appended to the 64 hexagrams, that’s also now referred to as the I Ching as well. And they’re usually poetic verses that read a lot like riddles. So, even if you know Chinese as a native speaker, it’s really hard to understand. Get two people to read the same text; neither two will say they fully understand what’s happening. But that would be the I Ching.

Angela Puca: Oh, that’s interesting. And how was it born historically?

Benebell Wen: So the legend goes that King Wen was imprisoned by the Emperor of Shang. He was part of a rebel or revolting group or tribe that then became the Zhou dynasty. But he was imprisoned by the Emperor of Shang, and while imprisoned, he took Fuxi’s Bagua—the eight trigrams—which was created by Fuxi 500 years ago, according to legend. He used the eight trigrams and then also the Loshu magic square, which came from Yu the Great, put these together, stacked the trigrams into binary hexagrams, and then from that, believed that the 64 hexagrams that he had created were the divination system. He used this divination system to, as he believed, predict the fall of the Shang Dynasty and the rise of the Zhou. And so the 64 hexagrams in I Ching are also, in that way, connected to the idea of the Mandate of Heaven. So the idea is that heaven told him through the I Ching that the Mandate of who could rule the people had shifted from one family to another family. So, they are interconnected.

Angela Puca: Was it born, so then, as a divinatory tool? Did it have, or does it have any other esoteric applications?

Benebell Wen: Oh yeah, so that happened in 1046 BC, right? And so, over the next three thousand years, many different Chinese scholars and many different schools of thought looked at the I Ching and came away with their own perspectives and their own uses for the I Ching. The Duke of Zhou, one of King Wen’s sons, is the one credited with writing the pithy texts that you see. So next to the 384 lines, there’s a little bit of verse that goes with it, and that’s credited to the Duke of Zhou, one of the sons of King Wen. King Wen not only created the hexagrams, the Yin-Yang lines but named the 64 hexagrams. And then later on, 500 years after the Duke of Zhou, came Confucius. We credit Confucius with writing out the Ten Wings and more of the explanation or explaining what these 64 hexagrams are. Whether it was Confucius who penned it or, you know, an army of Confucian scholars over hundreds and hundreds of years—you know, it depends on who you speak to, right? Whether you’re a practitioner who likes the mythology or you’re an academic historian. And so that is kind of where it came from.

Angela Puca: And how did the I Ching become popular, if we can say that it is popular? How did it get known in the Western world or worldwide?

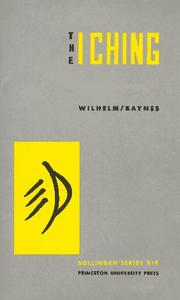

Benebell Wen: Well, first, it became popular first through Confucius. Confucius is credited with the Five Classics and five sacred books. There was the Book of Songs, which is poetry; the Book of Documents, which is like poli-sci, political science; and what else was it—philosophy and rhetoric. And then you have the Book of Rites, which is all about civil procedure and moral codes, and then the Book of Seasons, which is a book on history. And then the fifth book that he said was important for every scholar to know was the Book of Changes. And so these five books, throughout the history of the Imperial exams in China, had to be memorized and also had to be known by anyone who wanted to pass the Imperial examinations. So, any scholar worth their weight in salt had to know these five books, including the Book of Changes. And so that’s how I got interested in it. And because of that, every single scholar—to, you know, make themselves stand out—you’re going to produce commentary and a lot of your own thesis and dissertations on what these five books mean. The Book of Changes, the I Ching, is one of the more popular ones. So, over hundreds and hundreds of years, in multiple dynasties, you have many different schools of thought that come out. And one of those schools of thought, during the Qing dynasty, was the one that the politician in China—what was it? Wilhelm worked with, then translated first into German and then Baynes into English. And then I guess because of Carl Jung‘s fascination with the I Ching and seeing that these Eastern philosophies might explain some of his psychological theories that he couldn’t find a basis, a rational basis, for explaining in Western constructs—he took a great fascination with the I Ching. And so, I guess because of that, it then became popularized in the West as Carl Jung became popularized in the West.

Angela Puca: Yeah, I can imagine so. What are the differences between the way the I Ching is understood in Asia and in China and how it is understood in Western countries?

Benebell Wen: Well, one, I think right now, if we’re talking about today in the 21st century, the I Ching hasn’t been as popular among the laypeople in China or Taiwan. So, for example, on a very anecdotal observation level, if I go to Taiwan or to Mainland China, people just like me, the chances of someone like me being interested in the I Ching is, actually, very, very low. I think it is the same in the West, but at least I feel like more people know about it, but then they know about it as a fortune-telling or divinatory system, which is the origins of it is divinatory. But I think they have that idea that it’s either fortune telling and therefore more new agey or they think that the Wilhelm, they use the Wilhelm translation, which is, I think it’s kind of the same here in the West but at least I feel like more people know about it, but then they know about it as a fortune telling or divinatory system which is the origins of it. It is divinatory, but I think they have that idea that it’s either fortune telling and, therefore, more new-agey, or they think that the Wilhelm use the Wilhelm translation, which is filtered through a Christianized lens. So I think in the East, you’re less likely to find a Christianized filter over the I Ching, and so they see it more through the context of a lot of the stories, the legends and the mythology. In the I Ching, a lot of the lines from the I Ching are our idioms; it’s just that the Chinese people didn’t know where those idioms come from. So a lot of the things that we say like, ‘treading on the tail of a tiger’ or ‘hidden dragon,’ a lot of these little sayings or ‘the withering poplar blooms again,’ which so for example in present day when you say the withering Poplar blooms again is an idiom for an old woman or a widowed woman marrying a very, very, young man. But it came from the I Ching.

Angela Puca: And how does the I Ching work, in terms of, you know, if you want to use it for divination, how would you use it?

Benebell Wen: Oh, how do you use it? So the first approach, the first inquiry approach, is basically a form of casting lots where you’re using the yarrow stalks, and there’s a whole methodology to it. Even the methodology, if you know the numbers, follows, you do a lot of division, and then the remainders matter. So, it’s really interesting how even the concept of mathematics follows the mathematical formulas that the I Ching itself is based on. So you use yarrow stalks, the counting method, and then a lot-casting method to define where among the 64 hexagrams, which is seen as a circle—like a cycle—because after 64, it goes back to one. So, where are you located? So it’s almost like using a compass to figure out the exact location you are in. If you find the exact location, you can read around your location to figure out what’s happening in your life right now. The Yarrow stalk method is considered the more historical one. We believe that was the one that King Wen used because he had the dried yarrow stalks in his prison cell. And so that’s sort of where mythology comes from. I think the exact way that we do it, we can really only credibly say it goes back to 200 BC. So, the earliest version of the full divinatory process, step by step, using Yarrow stalks, we can only confirm at 200 BC. I think around 200 A.D. is when you have the three-coin toss method, or a coin toss method, that comes out. Later on, during the Song Dynasty, around the 1100s, Shao Yong and other different types of scholars came up with different approaches. And so, for example, there’s rice grain counting that you use, and Shao Yong used the Palm Blossom method. So there’s actually a lot of different ways to divine with I Ching; it’s not just one.

Angela Puca: And which one do you use or advise in your work?

Benebell Wen: It depends. For me, personally, it depends. If you read the Shi Su, which is the text that we rely on for the Yarrow stalk method, it talks a lot about the ritual process around divination. So you don’t just sit down and willy-nilly do a divination; there’s a lot that goes into it. It’s very, it’s a heavily, heavily ritualized process. And so if I’m going to the I Ching for something that matters a lot to me, like, you know, a matter of extreme importance, I will go through the entire and observe the whole ritualized process. In this case, I would use the yarrow stalks. You can also use the rice grains because it’s a very tedious method to use the rice grains divinatory method. But if I’m like having fun with friends or I’m trying to, you know, just like to have fun, or you know, there’s a drink in my hand, and I’m just having, you know, a light fun, you know, a light, flirty fun with it, then I’ll use the coin toss method. Or I’ll even use bibliomancy. I love doing that where you just, you know, open it to, you know, you just kind of, you know, point to any page at random, point to a line, and then read that. Then, find a way to see how that connects to your divinatory question. So, there are a lot of ways to approach divination.

Angela Puca: Yeah, I can see that. I was wondering, I guess, how does it differ, in your view, from other divinatory systems? I know that you also have an interest in looking at Tarot in your work. So how does it differ, for instance, from the Tarot? Obviously, the Tarot is very different from the I Ching in the way it works, but I was wondering, is there anything different about what kind of things you can foretell, for instance, with the I Ching compared to Tarot? And whether there are other differences that you could highlight?

Benebell Wen: Okay, one, I think it depends on who you ask. So I personally feel like you can get a lot more specifics, like very tangible, concrete—name, like dates. Maybe not names because I don’t know how to do the English conversion to the Chinese, but for sure, you can get very specific information about timing and location using the I Ching as a divinatory tool. But the reason I believe that is because of my approach to the two divination systems. So when I approach divining with the I Ching, I’m really working with the correspondences because there are so many layers and systems of correspondences built into the I Ching over the centuries and centuries of working with it. And so it’s not only the Wuxing, the five—I guess, movements or five elemental, alchemical phases—and what those correspondences are, but it’s also to the lunar-solar calendar, the 60, the 60-year sexagenary calendar that we use. It’s the fundamental basis of everything in Asia. And so, because there are so many corresponding systems when I do a divinatory reading with it, I also get a whole database of correspondences that I can look into. I can, you know, you can use it for medical diagnosis, not in a, you know, professional way, right? Not in a medical way. But a lot of times, people will use it to figure out what’s wrong with their health or with their body because there is that Wuxing, the five changing phases, correspondences to every part of the I Ching. So you can use that to figure out what in your own body is wrong; you can figure out what nutrients you need.

And so, to me, because of my approach to the I Ching, it’s a lot more specific. A lot of times when people read with the Tarot, most people, by and large, are going to rely heavily on the narrative imagery of the card itself, especially if they adopt the Rider-Waite-Smith System, right? And so you see a lot fewer people using Kabbalistic correspondences, astrological correspondences; those tend to be in the minority of people who use the Tarot. And so because it’s more of a, like, almost like a psychological projection tool, where you’re looking at the imagery and seeing what the images inspire from in your mind, that’s where you reach some level of truth or divination from the Tarot. Whereas the I Ching it feels, at least in my approach, a lot more technical. I don’t feel like I can really impose my own biases into it because there’s a set, established corresponding system, so I can’t really read into it.

Angela Puca: So, do you feel like it’s more similar to astrology than it is to Tarot?

Benebell Wen: Absolutely, because astrology was built into the I Ching. So, you have again, like, for example, the Ba-Zi—four pillars—form of fortune telling, which is a form of astrology in the East that is very much part and parcel to the I Ching. So, it is a lot more like astrology, especially since it’s saying that it maps out the heavens, it maps out the Earth, and it maps out the underworld. There’s that underlying theory or premise of the I Ching. So, in that way, it is like astrology, where you’re reading certain constellations and signs and interpreting them based on a system that you’ve established.

Angela Puca: Yeah, I think that I thought about astrology because when you said you cannot really put too much interpretation into it because it’s almost a mathematical system—you didn’t say “mathematical,” but that’s what I heard—basically, so it’s something that is technical. And once you have the input and how the output should be interpreted based on what’s happening, there’s a high degree of interpretation that goes into it. And to me, it feels like astrology is kind of the same; at least, that’s how it’s been described to me by many practitioners of astrology. So, that’s how I got reminded of that. So, a lot—I would say that it would be very interesting to expand a bit more on all the correspondences that you mentioned, like the five elements and all the others, what they mean and what they are, because I’m sure that many people might not be familiar with those.

Benebell Wen: Okay, so there’s a lot to it. Because in terms of the origins of the universe, I think that’s a good place to begin.

Angela Puca: Yeah, let’s begin with the origin of the universe; why not?

Benebell Wen: No, I just— I don’t know where to begin, that’s why. So, because there’s so much to explain. If I start here, then I have to backpedal and explain something.

Angela Puca: I’m fine with beginning with the origins.

Benebell Wen: Like, I don’t know where to start. So, there’s this idea that you have the Tao, and then the Tao is the entire universe, right? It’s everything. So, all things are this one—we’re all one. However, how do I understand this “one”? This “one” is way too difficult for me to understand. There’s no way I’ll ever understand what the Tao is. So, what I do is subdivide and cut up into little pieces so I can understand different facets of the Tao. And so, like, like a tangent, this idea of, are Asians or a lot of folk religions— are we pantheistic, are we monotheistic, or are we polytheistic? I think it’s a really interesting question that I don’t think, if you’re coming strictly from an Eastern cultural perspective, we think that deeply about, you know what I mean? Because we’re all of the above, and we don’t always understand. Like, we’re a little bit—or at least I get confused sometimes—like, why are we making, like, why do you care if you’re monotheistic, pantheistic, or poly—like, it’s you’re all of the above, right? Like, it’s kind of depending on where you are looking at. So, if you’re looking from up here, of course, you’re monotheistic because, at the end of the day, we believe it all goes back to the Tao. But, you know, if you’re looking down here to understand my everyday problems, if I have an everyday problem, who am I going to go to? I’m going to look at only one small facet of the Tao, and so then I’m polytheistic.

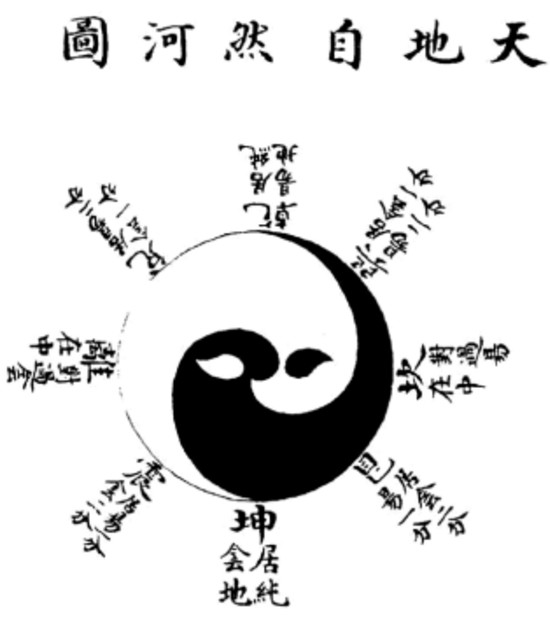

Anyway, so you have the Tao, and then we believe it’s subdivided into Yin and Yang. The entire universe is created by a binary code system, a lot like computer processing, where everything that we’re even seeing on the screen right now—the entire virtual world—is written through a program of zeros and ones. And so, we already have that belief built into the I Ching as well, which predates Taoism. It became absorbed deeply into Taoism, so now we say it’s Taoism, but it predates Taoism because it’s really the more indigenous beliefs of China that came out of the I Ching. And so, you believe in this binary code, and then if you do math and permutations, the binary code—that Yin and Yang—they subdivide, they create or combine into four, what we call the Sì Xiàng, the four images of God, and the four images of the Tao. And if you look at the seasons, like the cycle of seasons, and even the cycle of the day, how you track, you know, from night to day, from spring to winter, we use the four quadrants, four seasons. So, the four is that Sì Xiàng, and then those form the trigrams. So, when you get the binary plus the four, now you have eight trigrams. And those eight trigrams, so I always use the—what is it—the “hungry little Femme, the wise one must eat,” is the mnemonic I use. So, Heaven, Lake, Fire, the Wise, Women—so that is Thunder, Wind, Water, Mountain, and Earth.

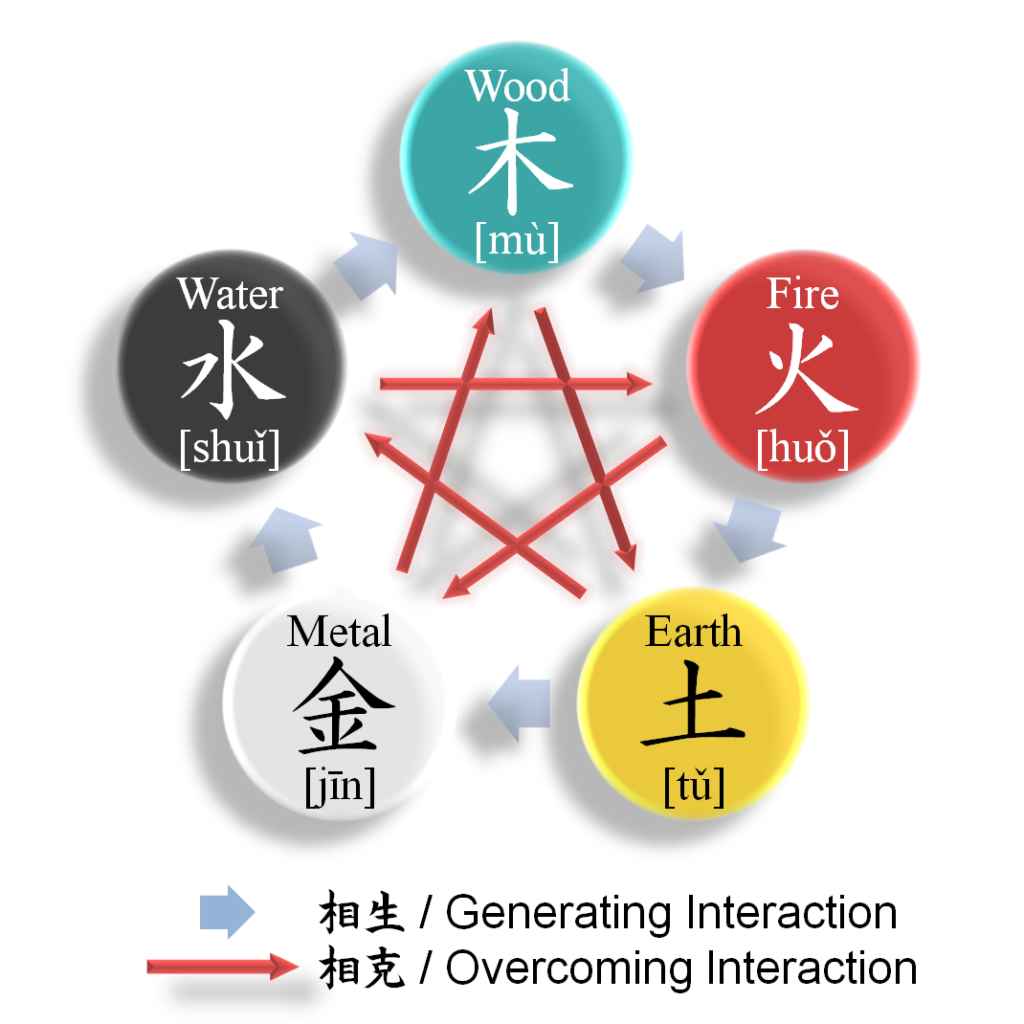

And so, because of those eight trigrams, they form the—the Bagua, and then there’s the Bagua, then rearranged to form something called a Lo Shu magic square. And then when you combine the two, that’s the reason we combine trigrams into the hexagrams because you’re taking from one arrangement of the trigrams, and then you’re taking from the second arrangement. And one represents the exoteric, and one represents the esoteric. Now, how did the four become the eight? So, we believe that there are five forces in the universe, five forces of change. And so, that would be the—that would be wood, fire, earth, metal, and water. And so, they also correspond with the five classic books. And so, these are the drivers that create everything. So, how do you move from Yin and Yang to the four faces, to the trigrams, and to the hexagrams? The driving force that pushes all of this into creation is going to be the five changing phases. And then that’s kind of where you begin.

Now, in terms of what they correspond with, there’s so much. So, the five correspond with the five different tastes, like I said, the five different books. Everything can be explained by the five phases. And so, it is used in traditional Chinese medicine, it’s used in all of our astrological systems and traditions. Even when we talk about the—we say there are five planets, and

then the sun and the Moon. It is also based on Wuxing. So the sacred seven, that’s how a lot of the ancients use, so the five planets and then the Sun and Moon, that is also based on the I Ching. And when you look at the days of the week, we also use the Wuxing to describe that. So because of that, every single part of everyday life, the universe, and our concept of the universe is built into the foundational architecture of the I Ching.

Angela Puca: So there’s the whole cosmology of the I Ching.

Benebell Wen: Yes, exactly. And I think that’s why it’s a book of philosophy, too. What we often miss is that it’s not just divination; it’s a book of philosophy. It explains that world history always repeats itself, and so that’s the reason it works as divination. The reason it works as divination isn’t something magical, mystical, and mysterious—although it is all of that. The logic behind divination is that everyone repeats itself, that we’re sort of fated to repeat. And so, you can figure out where you are located. If you know where you’re located, it’ll tell you what’s going to happen next. And so that’s why it feels like it predicts the future, but it’s more about just knowing the cycles of change. Sorry to interrupt.

Angela Puca: No, no. I think that’s a great point to make. So, is that how time is perceived? Because that makes me think, you know, it makes me wonder how time is perceived. I think there’s a long-standing debate in the esoteric community about how divination works in terms of, and I think, it has to do a lot with the concept of time. And I find it interesting. I think an interesting argument when it comes to divination and how it works is the idea that time is a human construct. So, we need time in order to understand what’s going on. So, even a movement or a set of words—if you don’t put them in the order of before, in between, and after, or past, present, and future—you’re not even able to compute them because we are not built that way. We are built with inner filters and inner categories, as Emmanuel Kant used to say. And the primary ones, according to Emmanuel Kant, were space and time.

So, I think that also enters the debate about whether divination interferes with free will or not. And I know there are many different views in the esoteric communities about that. Because some people say when you are doing divination, it’s just the path that’s ahead of you if you keep doing the things that you do now. But it’s not set in stone. And then there’s—and that’s usually called more divination—and then the fortune-telling tends to lean more towards the idea of “no, this is going to happen, there’s no way around it.” So, there are two different views about divination, and for some people, certain tools would lead more to the divination—the one that you can change, or at least to a degree, you can change—and the fortune-telling that is more about “this is going to happen, and whatever you do, that’s going to happen.” I was wondering, with the I Ching, which one is it, if any?

Benebell Wen: Well, so, because it’s built with the stacking of two different arrangements of trigrams—the two Bagua—while you have an early Heaven Fuxi Bagua, which is associated with the very first, early form of the eight-trigram arrangement, and then you have the King Wen Bagua, the later Heaven Bagua. So, the idea is that one of the series—one cycle of eight—represents the natural order. If left to its own devices, this is the unfolding path of the universe. And then the second is the occult or esoteric arrangement, which means, now that I know the rules and the axioms of how the unfolding path progresses, I can actually manipulate—using “manipulate” in a neutral way; it’s not meant to be negative—but just, I can. There are things that a human can do to exert their will and purpose over the flow of Qi in the life force in the universe, to then modify that path and change the path. Another reason we talk about the I Ching as a circle is that it is not only the wheel that keeps on going, where you know what the next step is exactly, but it’s also about understanding and manipulating space.

So, you can stand at different positions of that circle—for example, sample the epicentre. So, if you stand at the centre, then you can actually change, you know, the different radiuses. And so, in that sense, we’re not necessarily fatalists; we are only fatalists to the extent that, for the most part, most humans don’t possess the power, will and purpose to modify the unfolding path of the universe in its natural course. However, you can train and cultivate enough power to be able to modify the course of the universe. So, it’s both. It’s this idea of step one, rule number one: it’s really hard to change; this is the path; this is how it works. You can fortune-tell or define exactly what will happen next because you know you’re weak, and there’s nothing you can do about it. Or you can now learn what the path is and cultivate enough personal power to modify and change that. So, in that way, it’s very based on free will and also very optimistic because you can pretty much change anything so long as you cultivate the power to do so.

Angela Puca: And how do you cultivate the power to do so?

Benebell Wen: Depends on who you ask, I suppose. Simple ones? Qigong. I always say forms of amplifying the power of your Qi. And so, like a very martial arts example, right? So, because I haven’t been trained in martial arts if I punch something, it’s not even about my muscles, but I can’t consolidate my personal Qi in a way that can punch someone that hurts. But somebody who has the exact body type as me, everything exactly the same, but who trains in martial arts, their punch will be 10 times more powerful than mine because they know how to consolidate their Qi. So, that’s kind of how you do it—little ways of figuring out how to amplify, concentrate, and consolidate your life force. Your focus, in a very mundane psychological way of saying it, is: how do you focus, how do you prioritize, and how do you focus your energies and intentions? It’s a very simple, easy, mundane way of looking at that.

Angela Puca: And in terms of the practice to achieve this enhancement in your Qi punching?

Benebell Wen: I shouldn’t have used that example; that was a bad example.

Angela Puca: We’re gonna stick with it now; I’m kidding. But yeah, are there any exercises that are usually done by people who practice I Ching, or indeed yourself, to enhance how you can manipulate the I Ching? So that you can affect your destiny and even alter the things that have been predicted in a divination?

Benebell Wen: That’s the million-dollar question because there are so many different schools of thought, and over the years, this has been influenced by Confucianism, Taoism, and even Buddhism. I’m trying to make sure that I’m very clear on where what came from. In terms of esoteric Taoist practice, one of the things that people do, and it’s not just about making sure your divinatory practice is more accurate and more powerful, but also how you can exert your will in a very productive way over the forces of nature, is to look at the eight trigrams. They personify them as the eight Immortals or some form of divine being that’s been personified through the eight trigrams. And then you invoke these eight spirit beings, ascended masters—however you want to characterize or personify the trigrams—cultivate a close working relationship with those eight, and through that, you’ll dial into their pillar or channel of power. You’ll be able to siphon directly from their pillars of power. So then, you can choose to use Thunder, or you can choose to use Earth, or choose to use Water. That’s one more concrete, step-by-step way. There are also schools of thought that believe in karmic cultivation. It sounds kind of cheesy when you put it in English, but they’re called Schools of Beneficence, where doing good and being compassionate—literally just being a good person—will cultivate your Qi, make you a stronger person, and enable you to control nature if you are just a better person.

Angela Puca: Does it mean that nature is inherently good, then?

Benebell Wen: I think that’s—well, here’s the thing. “Good” is an opinion. What is good, what is evil? What benefits me is what I call good, and what does not benefit me is what I call evil. So, it’s completely subjective. I think those who are practising the Tao are not always going to see something destructive as evil or something dark because even if it’s destroying your city or something you care deeply about, there’s a greater good that maybe we don’t understand or we are not able to grasp. I’m so self-involved and navel-gazing, and it was really, really evil and bad for me; I can’t see how it was better for the greater good that it lays the foundation for something greater to come. So, there’s no good and evil; it’s just the cycles of change; it’s just creation and destruction over and over again. Sometimes, creation or destruction is bad for me; sometimes, it’s good for me, but that is my own vantage point. The only more objective vantage point would be creation and destruction, and then the five changing phases: transformation, segregation, and dissemination. These are five changing phases.

Angela Puca: Yeah, I really like that, and I think that it mirrors my way of looking at good and bad, at least from a cosmological point of view. From a societal point of view, then, it could be different, and it is definitely different for me. When you look at the greater picture, the universe, what is, you know, when you remove what is beneficial or what is harmful to people at the greater level, how do you define good and bad? And obviously, I don’t think that there is good and bad from a universal point of view. I think that it’s a cycle of creation and destruction. Sometimes, I also feel what we tend to call good is more in line with the creative force in the universe and what we call evil is more in line with a destructive force. For instance, when you cause harm, it is the destruction of something, and when you are helping somebody, it is aiding something creative – it is adding, it’s a plus – it is not a minus to a person, whereas harm is more of a minus, at least in the way I see things in my head. So I like that.

Benebell Wen: To defend – I mean, it’s

more of a Buddhist perspective, but to defend the Schools of Beneficence, it’s not good like it’s a different definition of good. The idea is that If you cultivate beneficence, you cultivate compassion and selflessness. So, eventually, your perspective is broader, and it is not so much navel-gazing anymore. So, if you cultivate good by this school of thought, you’re able to be more selfless and to let go of the biases of the self, and therefore, you can see creation and destruction on a more macroscopic vantage point. Therefore, you are more detached from your own personal pain and suffering, and you’re able to see what is good in terms of the flow of Qi. I think that is why they say that the practice of good is going to cultivate stronger power.

Angela Puca: I agree with Edward; chocolate is good objectively.

Benebell Wen: Yeah, I agree a thousand per cent. I have a sister – I don’t understand. I think that is very bad. How can you hate chocolate? But yeah, I have a sister who doesn’t like chocolate at all, which is good for me because I always get more.

Angela Puca: Yeah, that would be fine by me as well. I eat a healthy, chocolate-based diet.

[Laughter]

Angela Puca: I was wondering if you could elaborate – a bit more on those forces in the universe, the five forces. I have a million questions. I also noticed that there are a few numbers that recur right; not just one, but the five seems to be quite a recurring number.

Benebell Wen: Yeah, everything is either fives or twelves, the sixties and sixty-fours. When you do the division into the remainders, eights as well. It’s all aligned at the end of the day. Wood is rising energy; it’s growth. Fire is expansion. Earth is transforming energy. Metal is minerals, and it’s also stellar matter. Water is associated with mysteries. This cycle of changes creates the eight trigrams. Fire and water only have one trigram correspondence, and then the five work into it with the planets Jupiter, Mars, Mercury, Venus, and Saturn. Then the sacred seven also divide into the remainders into the I Ching.

Benebell Wen: Cultivating the power to exert your will over the course of events—be it in your personal life or in the broader tapestry of existence—requires a holistic approach in Taoist thought. It involves the triad of Jing, Qi, and Shen—essence, life force, and spirit. Cultivating Jing is about building your foundational energy and vitality, often through disciplined physical practices like Tai Chi, Qi Gong, and even things like nutrition and sleep. This is about harnessing the raw material of change.

Qi is the dynamic force that emerges from Jing, and this is cultivated through breathwork, meditation, and living a balanced lifestyle. Shen is your spiritual potency, your ‘presence’ in the world and in the metaphysical realities. This is cultivated through deeper spiritual work, wisdom, and ethical living.

Angela Puca: So it’s a multi-faceted process, grounded in both material reality and spiritual insight.

Benebell Wen: Exactly, and they’re all interconnected. You can’t build on one without the other. Your physical well-being contributes to your energetic life force, which in turn influences your spiritual potency. Once you have an adept mastery of these three, you’ll be better equipped to recognize the nuances in the flow of Qi or life force in the world and thus be more skilled at navigating and even altering it.

Angela Puca: It’s interesting because, in many forms of contemporary Western esotericism, there’s a focus on the cultivation of the “Will,” often in a somewhat abstract sense. The will is sharpened through practices like ritual, meditation, and magical work to effect change in conformity with the will. But it seems in the Taoist framework you’re describing, there’s a more grounded, comprehensive approach.

Benebell Wen: Indeed. The idea in Taoist philosophy is that you can’t divorce your ability to exert your Will from the realities of your physical and spiritual health. They’re all part of a harmonious whole. It’s about becoming a fully integrated human being capable of moving with the Dao yet also being able to direct it in some ways.

Angela Puca: That’s a beautifully comprehensive way of seeing things. It seems then, in the context of the I Ching, that if one is adept in the cultivation of Jing, Qi, and Shen, they could use the divination system not just for prediction or understanding the cycles of change but actually as a tool for exerting some degree of control or at least skilled navigation within those cycles?

Benebell Wen: Absolutely. The I Ching serves as both a diagnostic tool and a philosophical guide. Knowing how to “read” the patterns of change through the hexagrams gives you insight into the natural unfolding of events. But if you’re also skilled in the cultivation of your own energies and spirit, you can use the same hexagrams as a guide for what actions to take or avoid to harmonize with or alter the flow of Qi in a situation. So yes, it’s about both understanding and participating in the cycles of change.

Angela Puca: Fascinating. It’s like a manual for becoming a co-creator with the Tao itself.

Benebell Wen: Precisely. And it’s this duality—being both a passive observer and an active participant—that I find so deeply empowering in Taoist philosophy and practices like the I Ching.

Benebell Wen: Right, so in Taoist thought, the concept of ‘good’ and ‘evil’ isn’t seen in the same dualistic way that it is in some Western philosophies or religious systems. Nature is considered to be inherently balanced, following its own laws and cycles—what you might call the Dao. It’s not ‘good’ or ‘bad’; it just is. Our alignment with these natural cycles and laws, our ability to flow with the Dao, often is what’s perceived as ‘good’ in Taoist philosophy.

Angela Puca: So, it’s more about alignment and harmony than moral judgments.

Benebell Wen: Precisely. If you align your actions with the natural order of things, you tend to cultivate Qi more efficiently, and this enables you to live a more fulfilled, harmonious life. You become more capable of exerting your will upon the natural world, not in a domineering sense, but in a way that aligns with the flow of the Dao.

Angela Puca: And that brings us back to the concept of Free Will versus Determinism within divination and especially within the framework of the I Ching. The alignment and harmony you speak of almost sound like the cultivation of a certain kind of “aligned will,” so to speak.

Benebell Wen: Exactly. In terms of the I Ching, I see it as a manual for developing that “aligned will.” It gives you the road map to understanding the cyclical patterns in nature and in human events, and by understanding these, you gain the wisdom to navigate them adeptly. You can decide whether to flow with these natural currents or exert your will to make a change. But it’s not change in opposition to the natural order; it’s change that’s executed with an understanding of that order. You’re co-creating with the Dao, so to speak.

Angela Puca: That’s such a nuanced view and offers a rich field for understanding not just divination but also human agency within the metaphysical fabric of the Taoist worldview.

Benebell Wen: Absolutely, and I think it’s that holistic approach that allows the I Ching to serve not just as a divinatory tool but as a guide to living, a philosophy, and even a path for spiritual cultivation. It all goes hand in hand.

Benebell Wen: Right, and that light-hearted note about chocolate brings us back to the core point: the nature of “good” is deeply subjective, shaped by individual perspectives, experiences, and even preferences, like one’s taste for chocolate!

Angela Puca: True, and I think what you’ve said about the cultivation of beneficence opens up another layer of nuance. If one practices compassion and selflessness, they align themselves with a broader understanding of the cycles of creation and destruction, and thus, they are more equipped to act powerfully within those cycles.

Benebell Wen: Absolutely. The practice of “good” within these schools isn’t just about creating a moral identity. It’s about expanding your consciousness and widening your perspective so that you can engage with these greater cosmic rhythms more effectively. So, in that sense, what might seem like a moral or ethical endeavour actually has pragmatic implications for your spiritual and even metaphysical capabilities.

Angela Puca: That’s why I find conversations like these so rewarding. They allow us to dig deeper into the multifaceted ways in which various traditions approach the enigmatic nature of life and existence. Whether we’re talking about the I Ching, Taoism, or even different strands of Buddhist thought, these philosophies and spiritual practices offer tools for navigating the complexity of the cosmos.

Benebell Wen: Definitely. And it’s a journey, right? One that requires us to be humble and open to revising our understanding as we gain more experience and wisdom.

Angela Puca: Indeed, it’s an evolving dialogue, not just between traditions but within ourselves, as we refine our own philosophies and ways of interacting with the world. And hey, if chocolate can be a part of that dialogue, all the better!

Benebell Wen: I couldn’t agree more! Here’s to the continued journey of understanding, and may it be as sweet as the finest cocoa!

[Laughter]

Angela Puca: I was wondering, by the way, thank you to Andrew, João, and Edward for moderating the chat. So, I was wondering if you could elaborate a bit more on those forces in the universe, the five forces. And then I guess, because I have a million questions every time that you speak, it’s like I have a million questions. Like, I also noticed that there are, well, there are a few numbers that recur, right? Not just one, but the five seems to be quite a recurring number. So, I was wondering about that as well, but yeah, let’s start with the forces. Could you elaborate a bit more on the forces that are found in the universe?

Benebell Wen: Yeah, everything is either fives or twelves, the 60s and 64s. And then even when you do the division into the remainders, eights as well. It’s a whole thing like it’s really interesting. The more you learn about the various aspects of the I Ching and the Tao, they all connect; they all kind of align at the end. Everything all lines and reconciles with each other at the end of the day, which I think is why it’s a system that provides endless fascination. So, fire -we’ll begin with wood. Wood is rising energy; it’s growth, right? And then you have fire. Fire is expansion. So after energy rises, not creating, but it rises in some way—that’s the wood energy. A great way to think of that is the seed that grows into that little green sapling. And then fire is expansion. Fire is about attracting more; so, for example, I attract more to make myself bigger, and then I expand out, and I can progress. So fire is usually associated with progress, philosophy, logic, what else… like illumination. Any form of illumination, metaphysically, figuratively, and literally, is associated with fire.

Then you have Earth. Earth is transforming energy. An idea of that is the womb; so something in the womb, the energy is transforming. So even if you see the Earth under the ground as, you know, a womb of some sort, that is that transforming energy. And then you have Metal. Metal is minerals, right? And so it’s under the ground. What forms in the Earth are the minerals. And also, there’s this idea that the stellar energy, the heavens, is also Metal. So, stellar matter that comes down and hits the ground and is buried into the ground is also Metal. And then you have Water. Water is associated with mysteries because there’s this idea of the future being uncertain; it’s scary, it’s, you know, it’s like woo. And so water is always associated with intuition, psychic ability, mediumship, death, the afterlife, and all of that. So that’s the cycle of changes that goes through and through. And then this cycle of changes, as it moves from one phase to the other, creates the eight trigrams. And then the eight trigrams, it’s two-one-two-one, where you have fire and water that only have one trigram correspondence, and then the other three have two trigram correspondences.

And so the fire and water also, even though there’s two, again the mathematics, because the five works into it. So the five are the planets that go across for the I Ching, right? Jupiter, Mars, Mercury, Venus, etc., and Saturn. And then the two not only correspond with two of those five planets, but that’s where you find the Sun and the Moon. So the sacred seven also kind of divide into with remainders into the I Ching.

Angela Puca: That’s very interesting. And what about the Yin and Yang symbol, which is quite popular in the West as well? Could you elaborate more on that and its significance?

Benebell Wen: Yeah, with Yin, we often associate it with destructive energy; it’s dark, like, in the most simplistic term. It’s dark; Yang is light. And so anytime you have something that absorbs light and takes it in, then that’s the dark, that’s the Yin. Anything that emits light, that radiates with light, that’s going to be the Yang. As you have these two forces like that, and then we use that as a metaphor to explain everything else—creative and destructive, protons and neutrons, et cetera, et cetera. And so it depends on who you ask. I think it’s more of a categorical system. You see it as a truth; like, okay, this is the way, the Yin and the Yang, this is the fundamental core definition of Yin, and the core definition of Yang. And then you go out into this world and start categorizing what is what. Same with the Wu Xing, the five changing phases. You know that this is the core definition of the five, so you go out into the world to see what is what, And you no longer have differences of opinion because you have 3,000 years of scholarship. So you ask ten different scholars what corresponds with what, especially when you get into Traditional Chinese Medicine practitioners, you’re going to see some differences of opinion.

Angela Puca: Yes, and what about the association between Yang and the masculine and Yin as the feminine?

Benebell Wen: So, I’ve heard a lot of Asians say that came from the West, but in the research that I had to do for my book, that’s not true. You know, I’ve seen a lot of texts from the Taoist canons that show Yin and then have a drawing of a woman, and they show Yang, they’ll have a drawing of a man. And so I see it as just the evolution of human thought. I think it’s really, really easy when you look at how masculine-presenting and feminine-presenting, especially when you apply cultural norms to it, it’s easy to categorize, you know, the culturally socialized woman as Yin, and the culturally socialized man or masculine energy as Yang. It’s really easy to do that. But I think anybody who’s going to dig deeper into the philosophy of it is closer to the idea of anima and animus, where we each have both inside of us.

And this is why you have the Taijitu, which is the Yin and Yang symbol. It’s that idea that you have both within you; everybody has both, and it has nothing to do with your gender or sexual identification. It has a lot more to do with your own personality and how you navigate this world, whether or not Yang is more dominant or Yin is more dominant. And often, however often, because of the way we’re socialized, those who are Yang-dominant tend to exhibit what we call masculine traits. Even someone who looks very femme, if they’re Yang-dominant in terms of physical disposition and Traditional Chinese Medicine—again, using stereotypes—they tend to be louder, they’re more aggressive, they’re more ambitious.

Angela Puca: It’s me.

Benebell Wen: Even have these ideas, right? And then Yin, even a man— a man who is more Yin-dominant, you know, they’re going to be more pensive, quieter, more reactive than proactive. So we still have these socialized constructs, but you know, it’s one way of navigating this world.

Angela Puca: Yeah, absolutely, and thank you, Hank, for the chocolate bar [laughs].

But yeah, I understand what you mean, and I think that there have been many associations between the feminine and the masculine in that respect, even in contemporary paganism. And I think they kind of boil down to the idea of the projective and the receptive, and it’s not really— I wouldn’t see that as strictly connected to the idea that we have of biological sex or, indeed, gender.

Benebell Wen: I don’t think so either, and I don’t think the I Ching or the cosmological principles did either. I think it’s just how we, over the centuries, have socialized ourselves. Like I said, because what we’re doing is we’re observing the world and then categorizing what we see into the different categories, the different labels. And this is how we’ve categorized the labels, but it doesn’t mean it’s not subject to change or evolution of thought.

Angela Puca: Yeah, it does make sense. And so another thing that came to mind while you were speaking is that the I Ching doesn’t seem to be related to one religion, but it seems to be a bit transversal. So do you think that it has— well, because it has a specific cosmology, right? It’s built on a specific cosmology. So, do you think that it is compatible with certain religions only, and which ones would they be? Or do you think that it’s particularly connected to one religion as opposed to another? Or it’s been more influenced by one religion as opposed to another? So, my question is a broad question about how the I Ching relates to religions.

Benebell Wen: Well, a bunch of Jesuit missionaries from the 1700s and 1800s learned about the I Ching and believed it was proof of God, so they saw it as proof positive of Christian ideologies. Where, you know, obviously, there’s no direct historical connection, but it seems like the point is no matter who you are or where you come from, the I Ching is like a mirror. It reflects back who you are but then leads you to higher ground; it helps you to evolve and change. So it meets you where you are, and then it will show you more so that you can further develop and deepen your understanding of the world by starting with your own point of view. And you see that both in terms of not just religion but also politics because the I Ching was often used throughout history for statecraft and geopolitics.

So you see, for example, Japanese scholars who believed the I Ching proved that you need to be more nationalistic and authoritarian, and it exuded the conservative values of traditionalism. But then, during the Cultural Revolution, Chairman Mao cited the I Ching as proof that we needed a revolution. And so whether you are more leftist or rightist, you will see yourself reflected in the tenets of the I Ching. And then Buddhism, of course—very clearly, over the centuries—saw a lot of Buddhist tenets, and even a lot of the interpretations and commentaries on the I Ching that you see in Chinese are heavily influenced by Buddhism.

So if you are a scholar or an academic of I Ching in Asia, one of the things you do have to do is kind of dismantle what is coming from Confucianism, what is coming from Buddhism, and what is a little bit truer to what it was before the influences of those different religious tenets, right? And so a lot of times, it just depends on what time period you’re looking at the commentaries of the I Ching and what will be influencing it. Taoism, of course, as well— a lot of the I Ching is what formed what became the institutionalized tradition and religion of Taoism.

Angela Puca: So, if I understand it correctly, across the different periods in time, the I Ching has had different influences, different religious influences. The most prevalent one was from Taoism. However, as a divination device, it’s not necessarily connected to any religion.

Benebell Wen: That’s correct.

Angela Puca: That’s correct, okay.

Benebell Wen: I would say, if anything, it’s even—Chinese historians talk about this—when doing the research for the book, they say it’s ‘shamanistic historical origins.’ So, the indigenous shamanistic practices of King Wen, the king of the Shang Dynasty, that is where it would be rooted. If you had to connect it to a religion, it would be that—the indigenous shamanistic folk practices. And then, actually, it’s Taoism and Confucianism. So, a lot of how we—because Confucius is credited as authoring 50% of the I Ching—because, it’s also heavily influenced by Confucian thought.

Angela Puca: Yes, of course. And since we briefly mentioned Jung and his influence on popularizing, or at least bringing the I Ching into the Western World, could you elaborate a bit more on what Jung said about the I Ching and his interpretation and his works around it?

Benebell Wen: I think he’s most famous for believing that the I Ching explains his theory of synchronicity, where, you know, something happens—like it’s almost like acupuncture, I always use the metaphor of acupuncture—where one point here actually corresponds with something happening somewhere else, but they happen at the same time. So, if you see one, then you can understand the other. And that’s the divination, or that’s the concept of divination. So, he believed that synchronous or acausal synchronicity was explained by the reason that the I Ching was an effective tool.

I think it’s interesting also that lesser-known but is definitely there in the forward, if you read it, to the Wilhelm version of the I Ching, he does say some things that I don’t think have aged as well over the years, which is he didn’t believe that the Chinese understood science. So, he’s like, ‘Oh, this is a civilization that doesn’t understand math or science, but they have this really cool tool, the I Ching. So, wow, how did they come up with this? I guess it’s because they don’t really understand science. They are not, you know, restricted to the rigours of the scientific method the way we are. So they are able to come up with these more whack-a-doodle ideas. But by coming up with whack-a-doodle ideas, they hit on a truth.’ You know, the ‘a wrong clock is right twice a day,’ or something like that—that kind of idea. So, he did kind of say something like that. It didn’t age as well. I think it’s also interesting that he was very clear that the I Ching is not occult, and it’s not esoteric. He was like, ‘Oh, this is just philosophy, it’s proof of God, almost.’ But you know, like, I don’t think he saw it as something that was occult. But then, you know, people like Crowley took that idea from Jung and ran with it into the occult spaces. So, it is funny that even though he said the I Ching is not occult, his work or his popularizing the I Ching is what caused the I Ching to then become popular in Western occult circles. It’s just fun irony.

Angela Puca: Yeah, well, I think it was very common at the time of Jung to have an exoticizing view of non-Western countries, basically. So, there was this idea—I think that I’ve talked about that with other scholars that have been on the channel before as well—the idea that at the same time, you are exoticizing certain cultures and such, and countries, considering them backwards and not as advanced as Western countries, but that exoticization brings about a sense of mystery and a sense of the irrational. And so it’s like, ‘Yeah, they are the irrational, but when you want to learn about irrationality, that is the place to go.’ And that’s how you elevate, in a way, certain cultures to the realm of the spiritual ones, which may seem to a degree to be a way of reevaluating them, but it’s only reevaluating them in a specific lens and within a certain narrative where the Western countries are still the protagonists of the story. And saying, ‘You know, we are the advanced, intellectual, rational, civilized; they are the uncivilized and irrational. But look at them playing with those things.’ You know, ‘When we want to learn things about the irrational side, then we have to go there.’

So, it’s a bit problematic, and it’s something that you find quite often in the 19th century and in the 20th century. It’s something that is quite prevalent, you know, this idea of elevating Asian countries especially—even with India, you see that—elevating those countries, and then with the indigenous people, that happens as well—elevating them to those who have all the secrets of the universe because they are the irrational because they survive the civilization and the rational way of looking at things that we have adopted. So, it is problematic in that sense because it doesn’t really make certain cultures and certain people into a character, into a stereotype, not seeing the full picture.”

Benebell Wen: I think it’s also human nature because if you look at Chinese history for a long time, especially when they were in, during their own Enlightenment and Renaissance periods, and they were flourishing during their own Golden Age, we called ourselves the Middle Kingdom because we believed nobody else had anything to offer us. And then, I think it was 500 BC or what, the reason Buddhism became so popular in China is because it was this idea of an imported, exotic idea. And there was, again, that exotification of an imported idea, but then it just took root. And so, I think it’s part of human nature as well to centre ourselves, obviously, and then to see something that makes sense to us but we didn’t come up with as exotic and cool and want to take that and integrate it into our life. That’s just human nature, I think.

Angela Puca: Yeah, and there’s a long-standing—well, not a debate because actually, scholars agree on that—the fact that terms like magic and witchcraft are terms of othering. So when something, I mean, when something belongs to my religion, then it’s religious. When it’s something that somebody from a different religion does, then it’s witchcraft, and it’s magic. So it’s a term of othering. So I think that these are associations between this equation, almost, between something that is other, exotic, other, and mystical, witchcraft, occult. You know, I think that there is a little bit of that equation that has happened through history.

Benebell Wen: That is a big part of how I had to wrap my mind around how even Taoist mysticism is characterized or perceived. So for me, growing up, the whole time, I never really saw what I did as the occult, or esoteric, or magic, or witchcraft. I didn’t even know what it was; it was just, you know, it was so mundane and boring that I didn’t even care about it. In fact, I was interested in Western occultism because that was exotic to me when I was first here in the United States. And then, when people talk about Taoist magic as being, ‘Oh, that’s occult, that’s so cool,’ it took a minute for me to wrap my mind around, ‘Oh, so this thing that I think is mundane and boring and not interesting, you think of this as occult and witchcraft? Oh, very cool.’ So, it is interesting to see the different perspectives.

Angela Puca: Yeah, and it happens also, and sometimes certain occult systems within their own cultural context can be seen as superstitious as well. So when you don’t have magic and witchcraft as terms of othering, you have superstition as a term for setting aside parts of your own culture that are not exotic but are not accepted. I can see that with Italian witchcraft that I studied for my PhD, where people who started to value those folk magic practices were people that moved from one place to another where it was not that embedded in the local place. Because otherwise, they were seen as backwardly superstitious practices that, you know, who believes in that? But yeah, that’s quite interesting. So, how did Jung use the I Ching, then? What would they find valuable about it?

Benebell Wen: I didn’t study Jung too in-depth. I think just reading his writings on the I Ching is the only way I can glean any conclusions, so I really don’t know. But it’s interesting how it looked like he was using it for divination, but then he said, ‘This is not divination.’ So I’m confused, you know? But, like, so he seems to be using it the same way that we would use it and then call divination in the East. And then he says, ‘So I’m going to do this, but this is not divination; this is like philosophy and psychology.’ I’m like, ‘Okay, fair enough, you know.’ So I think maybe it’s just a difference in vocabulary sets. I think everyone’s talking about the same thing, but we’re using sets of vocabulary that we are comfortable with. So when he says what he’s doing is just almost like a projection, or he’s using it so that he can dive deeper into his unconscious, like the things that he’s pulling out when he’s using the I Ching, it triggers a recollection of aspects of memory that he couldn’t remember. Or it allows something from packets of data from the unconscious to surface into the conscious mind so he can become self-aware of it. So that’s how he used it. But then you ask somebody from China, ‘Oh, that’s fortune-telling,’ you know? It’s just different differences in vocabulary.

Angela Puca: Yeah, I was just talking with my patrons about that, which is an interesting synchronicity if we want to use Jungian terminology. Because I have a monthly call with all my patrons, and we were discussing the importance of terminology and definition. One thing that I was pointing out in that conversation is that people define things for very personal reasons, and that’s why there was a conversation about whether attempts even matter. And also, how, for instance, academics treat terms and how practitioners treat terms, and it’s very different because academics look at how many people, you know, and myriad different uses have been done of the term.

And what emerges from that whereas individual people tend to define things one way or another, depending on many personal reasons. So it could be that Jung wanted to label the I Ching in a certain way because it was convenient to him because it was not acceptable to call it occult or to call it divination in the circle that he had as the audience for his books at the time. So, I think there are very often personal reasons as to why people use certain definitions and certain labels. And that’s why I find so valuable the academic perspective as well. I mean, not that the individual practitioner’s perspective is not important, because, of course, it is. But we need to bear in mind that there are also very personal reasons behind why you say one thing as opposed to another, whereas the academic perspective tends to look at the thing from a broader perspective and tries to understand what the term actually means, as opposed to what individual people will define it as, depending on their circumstances and the potential benefits or downsides.

Benebell Wen: It is very much a double-edged sword. I think it’s absolutely necessary on the academic level to have those definitions. And then, the thing with that, though, is I think sometimes there’s a disconnect between how it’s used — you know, boots on the ground — in terms of the actual practitioners that the academics are studying. There’s a huge difference in how they’re using the words to describe and articulate the same exact thing. I think I don’t know how to fix that, but I do see that a lot, even in terms of how you know various aspects of Taoism, Taoist philosophy versus Taoist mysticism and religion in Asia. Whether Confucianism is that philosophy or religion, like you have a lot of these — what is Shamanism in Asia? There are a lot of these conversations that I think it’s really hard to get everybody on the same page because, like you just said, everyone is beginning with a very different set of definitions, and so I don’t know how to reconcile that. But that’s just a really interesting observation.

Angela Puca: Yeah, that’s a problem for us. Well, I do have my solution to reconcile that, but I don’t want to get into methodology too much. And since we are maybe here to learn about the I Ching, I can briefly say that I’ve talked in other videos about the methodology that is quite popular now in religious studies. And that’s discourse analysis — it’s Foucauldian methodology — where you identify patterns of meaning that emerge in the community. So it’s not about what the individual person says, but when you give numerous people — so that’s one thing that you find in social science — that there are apparent differences among different individuals, and those differences tend to subside when you look at a bigger scale. So you will find that when you have enough definitions from the practising community, there are patterns of meaning that are quite consistent. So obviously, there’s also another way of defining, which is more of an up-down way of defining, saying, “Oh, this is the meaning, and if you’re not using the term, that is not correct,” but it’s not the approach that we have in religious studies nowadays because we do value what people think. So that’s a 19th-century, early 20th-century approach that is outdated now. But it is interesting how, you know, you can find actual consistency when you look at them and what people say at a bigger, you know, a greater scale, especially when you don’t just allow them to define but also to explain why. Did you define it that way? When you have those two pieces of information, and you have enough data, you tend to find that there is actually some consistency, you know, enough consistency for you to determine the definition. That’s the methodology that I used to define Shamanism in my PhD.

Benebell Wen: As you were explaining that, I was wondering about, for example, Yin and Yang, right? And so I think there’s a plurality of opinions even within certain cultures, like even within certain homogeneous cultures and homogeneous traditions. There is a plurality of opinions on whether or not Yin is attributed to feminine and Yang is attributed to masculine. I mean, I have my firm opinions, but then, if I’m trying to be unbiased, I can’t discount the idea that Yin is feminine and Yang is masculine because that’s a really strong and popular perspective. So I can’t say that’s wrong. How would you reconcile that, where you have a very robust and strong opinion on two sides that are in direct contradiction with each other from the same exact culture?

Angela Puca: I think that sometimes contradictions are not as contradictory as they may seem at first. So I think that you reconcile that by qualifying further. So it’s like when you say this is feminine and this is masculine, what do you mean exactly? And when you ask these questions, you will find that things are perhaps not as contradictory as they may seem at first. At least, that’s my experience. It’s just that I think human beings tend to summarize things. You know, I think that the problem with labels is that they are extremely concise, and so you just have to pick one thing, and that’s what is the clearest for you. But then, when you ask people to elaborate and to qualify further, you will find that there are many more liaison points than you would have anticipated. So that would be my prediction, but if you try that, let me know if that works.

Benebell Wen: That’s so great. I love that, and it also shows the importance and value of discourse. So I really love that.

Benebell Wen: It is very much a double-edged sword. I think it’s absolutely necessary on the academic level to have those definitions. And then, the thing with that, though, is I think sometimes there’s a disconnect between how it’s used, you know, boots on the ground, in terms of the actual practitioners that the academics are studying. There’s a huge difference in how they’re using the words to describe and articulate the same exact thing. I think I don’t know how to fix that, but I do see that a lot. Even in terms of various aspects of Daoism, Daoist philosophy versus Daoist mysticism and religion in Asia, whether Confucianism is that philosophy or religion—like you have a lot of these “What is Shamanism in Asia?” There are a lot of these conversations that I think it’s really hard to get everybody on the same page because, like you just said, everyone is beginning with a very different set of definitions. And so I don’t know how to reconcile that, but that’s just a really interesting observation.

Angela Puca: Yeah, that’s a problem for us. Well, I do have my solution to reconcile that, but I don’t want to get into methodology too much since we are maybe here to learn about the I Ching. But I can briefly say that I’ve talked in other videos about the methodology that is quite popular now in religious studies, and that’s discourse analysis, a Foucauldian methodology where you identify patterns of me

aning that emerge in the community.

So it’s not about what the individual person says, but when you give numerous people—that’s one thing that you find in social science—there are apparent differences among different individuals, and those differences tend to subside when you look at a bigger scale. So you will find that when you have enough definitions from the practising community, there are patterns of meaning that are quite consistent. So, obviously, there’s also another way of defining, which is more an up-down way of defining, saying, “Oh, this is the meaning, and if you’re not using the term, that is not correct,” but it’s not the approach that we have in religious studies nowadays because we do value what people think. So that’s a 19th-century, early 20th-century approach that is outdated now. But it is interesting how, you know, you can find actual consistency when you look at them, and what people say at a bigger, you know, a greater scale, especially when you don’t just allow them to define but also to explain why did you define it that way. When you have those two pieces of information, and you have enough data, you tend to find that there is actually some consistency. You know, enough consistency for you to determine the definition. That’s the methodology that I used to define Shamanism in my PhD.

Benebell Wen: As you were explaining that, I was wondering, for example, about Yin and Yang, right? And so I think there’s a plurality of opinions, even within certain cultures. Like, even within certain homogeneous cultures and homogeneous traditions, there is a plurality of opinion on whether or not Yin is attributed to feminine and Yang is attributed to masculine. I’m very—I mean, I have my firm opinions, but then, if I’m trying to be unbiased, I can’t discount the idea that Yin is feminine and Yang is masculine because that’s a really strong and popular perspective. So I can’t say that’s wrong. These same things, like, how would you reconcile that where you have a very robust and strong opinion on two sides that are in direct contradiction with each other, from the same exact culture?

Angela Puca: I think that sometimes contradictions are not as contradictory as they may seem at first. So I think that you reconcile that by qualifying further. So it’s like, when you say this is feminine and this is masculine, what do you mean exactly? And when you ask these questions, you will find that things are perhaps not as contradictory as they may seem at first. At least, that’s my experience. It’s just that I think that human beings tend to summarize things. You know, I think that the problem with labels is that they are extremely concise, and so you just have to pick one thing, and that’s what is the clearest for you. But then, when you ask people to elaborate and to qualify further, you will find that there are many more liaison points than you would have anticipated. So that would be my prediction, but if you try that, let me know if that works.

Benebell Wen: That’s so great, I love that. And it also shows the importance and value of discourse. So I really love that.

Angela Puca: Yeah, I think that one thing that we generally need more as a society, and it’s a great part of the academic world, but I think that the general public would benefit from that, is the value of complexity and nuance. So it’s not just about a yes and no, you know, is this this or is this that. It’s more about the complexity, the nuance; what is the reasoning behind associating these two things? What is the reasoning for you? When you allow people to elaborate on things, you will find that you know there’s much more that emerges, sometimes quite often, actually. I think that there are fewer contradictions than you would think, and probably, they will also apply to people who have different political views. Not always because sometimes it’s just irreconcilable, but you know, with people that are a bit more moderate, you will find a certain reasoning behind things that may underlie similar needs that tend to be expressed in ways that appear different.

Benebell Wen: Yeah, and then understanding a person’s why and how causes you to empathize with them. And then when you empathize with them, it’s a little bit harder to dismiss, you know, their values and their importance. Whereas if you use labels, it’s very easy for me to say, “Oh, you are this label, I am that label, we’re obviously different—end of discussion.” Yeah, the discourse is the why and the how is very important.

Angela Puca: Yeah, I think that’s true. The complexity is always something that I advocate for.

Benebell Wen: That’s how I approach occultism, too, even the correspondences. It’s always, for me, not about how you interpret the lines of, you know, for example, if you do divination and you see a verse in the I Ching, how you interpret that and apply it to your everyday life and translate that to something that is coherent to everyday life. I think it’s not the end result that matters as much as the why and the how—to understand how that translator, interpreter, or diviner arrived at that conclusion. I think that is the value.

Angela Puca: Are there certain questions that the I Ching cannot answer, or can it be used to answer any type of question?

Benebell Wen: I think the most common sentiment is that it can answer any question whatsoever. However, what is the value of asking certain questions? And do you, knowing certain things – is it going to be helpful to you, or is it going to be detrimental to you? And so there is wisdom in knowing what questions to present to the I Ching. But it doesn’t mean that there are only certain questions that the I Ching will answer. So the principle is that I can bring any question whatsoever; there’s an infinite amount of topics that the I Ching can answer because it represents all of truth—the universe of truth and the cycles of truth. But then, is it wise for me to ask certain questions?

Angela Puca: Yeah, that’s something that I’ve heard from Tarot readers that I know as well, that it’s also, you know, there’s also the element, and I guess that a question that I’d like to ask you is, what is your favourite experience with the I Ching if you don’t mind sharing?

Benebell Wen: I would say my favourite experience was when my grandmother passed on, and I wrote about this in, I think, the introduction or the forward. I had never thought of the I Ching as being used as a tool for mediumship at all, you know, the culture I grew up in; it’s just not something that had crossed my mind at the age that I was when my maternal grandmother had passed on. But I was in college, and I wasn’t allowed to go back to Taiwan to attend her funeral or any of that. So I just disconnected from her, and there was no way for me to be able to grieve over that. And so I used the I Ching, like I don’t know what it says, intuition, you’re just motivated by something within. So, I decided to try to communicate with her through the I Ching. And so, at least according to my perspective, I believe that I did. I went through, you know because you wanted to do something; you go through all of the ritual, all the ceremony, the pomp and circumstance. I’m going to make this happen. And so I did all the things that you’re supposed to do to contact the dead if you’re using the I Ching. And so that was, and I believe that was my way of, you know, kind of having closure with the fact that I couldn’t attend my grandmother’s funeral, I couldn’t be there to grieve her.

Angela Puca: Oh, that’s lovely.

Benebell Wen: So that’s obviously the most memorable one.

Angela Puca: And what would people find in your book?

Benebell Wen: So, half of it is the cultural and historical context for the I Ching so that you can approach the practice of the I Ching from a very informed perspective. So I really wanted to show that there’s no right or wrong; there’s just a diversity of schools and systems of thought over the centuries, over the dynasties. I tried my best to kind of cover, like you know, in like Cliff Notes—nuts and bolts—brief summaries of the various schools of thought and approaches to the I Ching over the dynasties. So you have that, and then you have: why do we say this is a shamanistic historical origin? Like, why do we say the I Ching is shamanistic in its origin? And so I talk about that as well. I also talk about the everyday folk practice. How it is actually used if you go to Vietnam if you go to Thailand, if you go to the Philippines, you go to Taiwan, you go to Hong Kong, you go to various parts of China—and it matters whether it’s the North or the South, that’s a huge difference. So, depending on which region you go to in China, what will you see? What are the practices of I Ching you’re going to see? And then the other half is the actual classical translations from the classical Chinese into English.