Dr Angela Puca: Hello, Symposiasts. I’m Dr. Angela Puca, a Religious Studies PhD, and this is your online resource for the academic study of magic, esotericism, paganism, shamanism, and all things occult. Today, we’re adding a little bit of Folklore as well, although it’s something that’s also part of the topics I address in my symposium. Before we dive in with our special guest today, I’d like to remind you that Angela’s Symposium is a crowdfunded project. So, if you have the means and want to help keep this project going and allow everybody to access academic, peer-reviewed knowledge on the topics that I cover on the channel, please consider supporting my work. You can make a one-off PayPal donation, join memberships, or my Inner Symposium on Patreon. There’s also the option of Ko-Fi now. You’ll find all these options in the info box, show notes, and in the bio everywhere. So, thank you all for considering. Thank you to Andrew, Edward, and João for moderating the chat. And now, let’s bring on our guest today. So today, we have Icy Sedgwick. Have I pronounced your surname correctly?

Icy: It’s Sedgwick, but I know that obviously depends on whether you’ve got that collection of letters or not.

Angela: Thank you so much for accepting to be on my show, Angela’s Symposium. Andrew is the moderator, the one who introduced me to your work. So, could you tell us a little about yourself before diving in?

Icy: I’m doing a PhD in Haunted House films—yes, that’s a thing, and people always ask that. I also run a Folklore podcast and have basically become a Folklore researcher/writer kind of by accident over the last six years, I think. So, my focus is usually on Northern European Folklore, just because that’s where I am. But that kind of takes in all sorts of stuff, including ghost stories, fairies, local legends, superstitions, and even urban legends occasionally, although they’re not necessarily my favourite.

Angela: And what got you into studying these for your PhD?

Icy: For my PhD, it was—how do I put it? I’d done something similar for my MA dissertation because I’d looked at the uncanny in domestic spaces. Then I wanted to do a PhD, and I was like, “Oh, I’ll do the haunted house element,” because I had been doing sort of female monsters as well, films like “Carrie” and stuff like that. Then I said, “I’m more interested in the ghost side of things.” It’s changed a fair bit, as they sometimes do, over time and the number of supervisors I’ve had. I’m specifically looking at haunted houses in American cinema, sort of from “Amityville Horror” onwards. I’m looking at them less in terms of what they represent, spectrally because there’s a really big thing in Gothic studies, particularly of looking at things as metaphors, which is fine. There’s some really awesome stuff being done like that, but I’m also like, “Yeah, but it’s also a film.” So, my main point of focus is looking at how hauntings, ghosts, demonic entities and so on are created using the language of cinematography, set design, and sound design as well. It’s like, how do these technologies of cinema actually contribute to making ghosts and so on? If I had more space, I would probably also have included costume and makeup as well, but that’s possibly a rabbit hole I don’t have time to fall down at this stage.

Angela: Is it a practice-led PhD?

Icy: No, no, it’s old—it’s a theory PhD. But I had, like, old terminology and so on; a lot of my theorists are actually sort of practitioners. So, it’s cinematographers, sound theorists, and people like that. So, it’s quite nice to include theory and the people who actually make the films in the first place.

Angela: Yeah, absolutely. How does it intersect with your online project, podcast, and interest in Folklore and Pagan themes?

Icy: It’s mostly the ghosts’ end of the spectrum. So, where obviously a lot of Folklore can include ghost stories—and I know some people don’t include ghosts as part of Folklore, which I think is a great shame—it has been quite useful. Because of that fact, you start spotting elements in, say, set design and other parts of the way that the films are made that you see coming from Folklore. A standard example in some films is—and actually, I’ll stick to one, “The Conjuring” in particular—there’s a whole big thing about the fireplaces in the house. They’re just kind of in the background in the set design, but they’ve all been used for something else. And there’s obviously all the stuff in Folklore about people blocking, or should I say, blocking fireplaces using things like apotropaic marks and other devices or practices to try and prevent evil from entering the home through the fireplace. Obviously, I always think it is quite funny when you get to popular belief about things like Santa Claus, but that’s just my giggle.

Angela: And what brought you to start your Fabulous Folklore Podcast? I think you also have a YouTube channel, so people go check it out. I can already see that Andrew has posted it in the chat.

Icy: It was really an accident because I’d been blogging about Folklore as part of the Folklore Thursday hashtag on Twitter—I refuse to call it X. I’d been putting up the blog posts, and then I was reading a book about marketing. It said that once you get to a certain point, you should diversify what you’re doing, like writing – adding video or audio. So, for accessibility reasons, I recorded an audio version of the blog post and put that in the blog post itself. Just for a laugh one day, I uploaded the RSS feed to iTunes, as it was then, and it was like, “Oh, now you’ve got a podcast.” So, I started podcasting kind of by accident.

I added YouTube more recently, but I’m just putting the audio episodes on YouTube because it’s too much to create videos weekly. Many people now listen to podcasts through YouTube; there’s an entire feature for that. It just gives people an extra point of entry. One of the things I like about having the episodes on YouTube is the fact that people can comment directly underneath. There isn’t an option for that on other podcast platforms; you can leave comments on Spotify, but I can’t respond to them. So, you can’t get that dialogue going in the comments like you can on YouTube.

I never wanted Fabulous Folklore just to be me talking; I’ve always wanted to have audience participation, for want of a better word. For the last couple of episodes that I’ve done, it’s been really nice for people to tell me Folklore on that subject. It’s like collecting primary research and sharing that, rather than just relying on the same old sources that everybody else already has.

Angela: Yes, absolutely. So, entering now into the realm of paganism and Folklore, how do you think Folklore informs pagan practices? I’m talking more specifically about contemporary paganism because I know there’s a whole conversation about pre-Christian forms of paganism. At the moment, I’m editing a book on paganism, and there’s been a whole discussion about how historical paganism is not capitalized, whereas contemporary Paganism gets capitalized. So, how do you think that Folklore informs and affects contemporary paganism and pagan practices?

Icy: I think, in some ways, Folklore can give you a nice place to start. If you just want to get started with ordinary, everyday practices, shall we say, not big massive rituals or anything like that—there are so many little bits and pieces in Folklore, like particular herbs that you might have around your house or something really basic as putting a horseshoe over your door. In a way, I think that helps to – not legitimize, that’s the wrong kind of word, but to anchor your practice in the sense that this is something that people have done previously. Because I think there is that issue, particularly with some of the reconstructed traditions. Many of these paganism branches are reconstructed because we don’t know what people did that far ago because there aren’t records. Where people have reconstructed them, I feel like Folklore helps you fill in the gaps a little bit because they have been collected and documented. That in itself also poses problems, but I think it does give you an idea of what actual people were doing, rather than, if you look at, the Order of the Golden Dawn, who are off doing their own magical thing, which is perhaps not as accessible as some of the other practices. If you look at Folklore around home protection, for example, you can see echoes of it even if you go back to some of the Roman sources, who were really helpful and wrote a lot of stuff down. You can see how these things, which are essentially ordinary people’s beliefs, can then help to underpin different pagan practices in a way that I think is helpful but sometimes gets co-opted in the wrong way.

Angela: What do you mean in the wrong way?

Icy: I think it’s a more specific thing, so, for example, when you look at Clootie Wells. Back then, people would take a length of fabric from something that would biodegrade because that’s what they had in those days, and if I remember correctly, it depends on the well. Generally speaking, you would bind it around the affected thing that you were trying to heal. Then, you’d dip it in the water and tie it to a tree. As the piece of fabric rotted away, it should take your illness with it. It’s a nice practice in a lot of ways. However, modern Clootie trees have people hanging up nylon, polyester, rayon, and all these fabrics that famously don’t biodegrade. In some cases, it’s damaging to the tree, and in other cases, it’s making the area look – I don’t want to say untidy. People want to join in with the tradition but not necessarily with the actual practice that underpinned it in the first place. It becomes this whole other thing, which wasn’t the original intention. There have been recent news stories about people setting fires at Bronze Age circles. And it’s kind of like, why? What were people trying to achieve by destroying an ancient site? That’s what I mean, where I think that people sometimes take these ancient practices and just take the bit they like. It creates a set of practices that end up being more damaging than the people themselves may even realize that they are.

Angela: That’s interesting. It also seems like Folklore, for many people, is a gateway into Paganism or Pagan beliefs and practices. Speaking of which, I understand that you are interested in otherworldly beings, whether we can call them fairies and ghosts. Can you tell us more about these and how they intersect Folklore and paganism? Is there a difference in how these are seen or interpreted, and the beliefs around them and even the practice around them in Folklore as opposed to contemporary paganism? If there is a position.

Icy: It’s funny because I think there’s so much lovely crossover, and they’re overlapping in quite a lot of interesting ways. So if you look at a lot of the stories, for example, Boggarts, they’re sort of like the Brownie gone bad. So if you have a Boggart in your house, they’re famous for messing things up, and if you leave things tidy, they’ll put them in disarray. There’s a crossover from them with things like Poltergeists and whatnot. I often wonder if we’re talking about the same things but just with different names. Particularly when you look at some of the older fairy encounters, and then people have discussions about other spirits that they might have encountered, and so on, and they all sound quite similar. There are a lot of lovely crossovers between certain types of fairies and ghosts, like grey ladies and white ladies and things like that.

I do think there’s some use in categorizing them, so you’ve got fairies, ghosts, and demonic beings, although that’s starting to get into a grey area. But then what’s really interesting is how many people in contemporary paganism take some of these spiritual beings and then work them as part of their practice. So I’m thinking here of the people who work with fairies and so on, which to anyone who looked at the original Folklore about fairies is like, “I wouldn’t be so keen on doing that.” Fairies in Folklore aren’t really famous for necessarily being particularly helpful to humans. But then people have taken parts of the fairy lore that work for them and then created this whole form of practice because that’s how they encounter these particular beings or this particular part of the environment, which is really cool.

And I think you also get mythological creatures that turn up in these kinds of guises, like dragons are a particularly famous one. I’ve seen quite a lot of stuff recently about people wanting to develop practices with like mermaids and water spirits and things like that. So it is really interesting how Folklore provides this cast of characters or archetypes, and so on that people can engage with in a more practical way, I think, through different paganism paths, if that’s the right term. I think this is one of the advantages of paganism as a whole; because there’s no single dogma, you can approach it in a way that suits you. And then, of course, you’ve got other people, quite a lot of people that I know are engaged in spirit work and do quite a lot of things with ancestral spirits or even encountering the dead in different forms – either helping them or whatever they need to do for that particular spirit.to generally So, I think it’s interesting how all these aspects of Folklore appear in modern practice, creating a nice engagement with the wider environment that you might not otherwise have without that belief system in place.

Angela: Can you expand a bit more on how fairies are seen in Folklore? By the way, are you referring to British Folklore?

Icy: Mostly, yes. I’m thinking particularly of a lot of the English Folklore. Famous story types, like the tale of the Fairy Midwife, do appear elsewhere around the British Isles and, no doubt, I would think in Europe as well. The tale of the Fairy Midwife is quite a famous one, and it’s not the Midwife that is the fairy, but it’s an ordinary midwife who’s called usually in the middle of the night to a location that she does not recognise, and she is there to deliver a baby. She’s supposed to anoint the baby’s eyes with this ointment when she gets there, but she’s not supposed to touch her own eyes. And for some reason, usually by accident, she rubs her eye or something like that and ends up with this ointment on her eye, and then she can see that the person that she’s dealing with is not actually a rich woman in a wealthy house or whatever. It’s actually a fairy in a cave or something like that. She doesn’t let on. She gets paid for her job, and that’s all good; she gets paid and goes back to her life. But if she inadvertently lets on that she has seen the fairies in her ordinary life – usually at a market, and then, because of the fact that they realize they’ve been seen, they invariably blow into her face and actually blind her either in both eyes or just the one with the ointment on. And I always look at stories like that, and I’m just like, yeah, I wouldn’t cross them. I had quite happily leave them be.

And then, of course, you’ve got the legends of changelings as well. This idea of fairies swapping a human baby for one of theirs and again that doesn’t, to me, necessarily scream benevolence. Although again, I think because you can divide fairies into so many different types, and indeed Catherine Briggs did, in her “Encyclopedia of Fairies.” I think that it’s probably not that helpful of me to kind of lump them all into one category.

Angela: Yeah, that’s also fair. And are there different types of fairies in English Folklore?

Icy: There are so many types of fairies; it’s fascinating. You have everything from the Will o’ the Wisp, which probably has variations all over Europe, to Knockers in Cornwall and the Northeast of America. These Knockers are known for making noises in mines. Some say they warn miners of impending disasters, while others argue they’re causing cave-ins. Most lean towards them being helpful. Then you have Brownies, who tidy up or mess up your house depending on its initial state. They’ll leave if you give them gifts, so there’s a range of behaviours there.

Icy: There are so many of them. It’s really interesting because you end up with everything from like the Will o’ the Wisp, which there’ll be a variation of, I’m gonna hazard a guess and say, pretty much all over Europe, and then you’ve got sort of fairies like the Knockers that you get in Cornwall, but you also get them in the Northeast and in America, and they’re the ones who make noises in mines. Sometimes, Folklore has them as warning miners of impending disaster. Other people have said, “Oh no, they’re knocking because they’re going to create a cave-in.” But most people tend towards them being there to warn people, so they’re at least helpful. And then, of course, you’ve got the likes of your Brownies, who will tidy your house if you’ve left it untidy and then mess it up if you haven’t and so on. And the ones who kind of work hard doing chores around the house at night as long as you don’t give them a gift of anything or then they’ll leave. So there’s quite a few like that.

But then you go into the realms of the fairy animals for want of a better description. So you have your Black Dog spirit, and I suppose probably; are we going to call it a fairy? Yeah, the Kelpie would probably be the one most people might have come across, and that’s the water horse again; these appear all over Europe with different names, where if you see this just a horse kind of grazing near water and then you touch it you kind of almost get stuck to it, or if you climb on his back you then can’t get off again, and it just drags you into water and drowns you. So again, it’s kind of like not very nice. So you do get this huge spectrum of fairy-like creatures that some of them like humans, some don’t, and some seem completely indifferent. So it just depends on which piece of lore you’re looking at.

Angela: Is there a motivation as to why they mess about with people’s things and lives?

Icy: It’s difficult to tell. I think, with the brownies, there are so many different stories. In some cases, they’ve somehow become attached to the family, so the family almost kind of passes them down. Some of the stories try to claim that they like helping and doing jobs around the house because it makes them feel useful. I don’t know how much I buy that one; it might just be people trying to make themselves feel better about it.

But I think it’s difficult trying to assign motivation to anything fairies do. In many of the Folklore, they seem to just pretty much please themselves, which is why some of them will be mischievous and play tricks just because they find it funny. You know, there are people who are like that, so I suppose they are weirdly human in that way. Sometimes they don’t have a motivation.

Then there are other ones, like the Banshee, for example, who have a specific job. Her role is to announce a death, usually in a specific family, and she kind of passes it down through the family as well. So that’s literally what she does. I think it’s interesting that some of them literally do what they do just because that’s what their role is for. For Brownies, it just seems to depend on the story that was collected at the time as to what the Brownie got out of it.

Angela: Yeah, that’s very interesting. Thank you to Vocatus, Mark, for your donation, and thanks to Rachel for saying, “Thanks for this great interview, Dr. Puca and Icy.” We have a question from one of my patrons who says, “At what point is a mythological monster not considered a fairy? Is there a set of criteria to help with the classification, or is this just decided over time?”

Icy: That is a really good question. I think it seems to be, from what I can gather, there seems to eventually be some kind of cut-off point. Anything that’s discussed in ancient sources tends to be more mythological. And then anything that’s kind of more recent, and by recent, I mean, you know, you’re still talking a few centuries. So, if you look at something like the Unicorn, for example, Pliny talks about them. I’m convinced Pliny is describing a rhinoceros; I believe he’s talking about a rhinoceros. You get things like the Manticore as well.

So yeah, it’s a very good question, actually, because then I look at other things, like we’ve got some dragon stories in the Northeast, and they’re called wyrms. They’re these great long serpent-like dragons, and they’re not considered mythological. But they’re also not really considered fairies either; they’re just monstrous. So that is a really good question. There almost seem to be three categories: mythological, monstrous, and fairy. I think it possibly is just a question of when the story was collected as to which bucket it kind of sits in.

Angela: I’m wondering whether your question, Arcane Whiskers, is about what’s the difference between something being considered Folklore and something being considered mythological. If that is the question, I would say that something that is Folklore is very unstructured; it is living and breathing. Something that is mythological is historical and is usually part of the corpus; it’s part of a wider narrative. So, in mythology, you often have pantheons, you have a whole backstory, theogony, and genealogy, whereas Folklore is very much a mess. It’s not as structured, it’s not as tidied up; it’s like people. People have different beliefs, and you will find that one person may describe a specific entity in one way and another person in another way, but since it is something living and breathing that people are still engaging with. It changes over time; it’s very malleable; it’s not structured. I think that’s the difference that I would see between Folklore and mythology. I’m not sure that it is a super accurate answer, but it’s my perception. Would you agree with that, Icy?

Icy: I think one thing I would like to add to that as well is that mythologies tend to be, like, they’re almost fixed. Over time, you get a description of a dragon or a griffin, and that’s what it becomes. Whereas if you look at Folklore, it can vary just by going down the road. They’ll have a slightly different version of something from one village to the next. So yeah, it is incredibly messy; you are correct on that one. And it’s a nightmare sometimes trying to go, “Are these the same thing? They’ve got different names, but they kind of sound the same.” Whereas with mythology, it’s like, you know what this is, so it’s nice and organized.

Angela: Yeah, and I’m sure that even in history, there will be a difference between what’s written in mythology and what people believe and what people practice; that’s the long-standing difference between institutionalized religions and living religions that in religious studies, we talk about. And even this is particularly prevalent in non-dogmatic religions, and paganism is, of course, an example, but even with religions that are dogmatic by design, like the monotheisms, even in those cases, you will find that what people do and what people practice and how people talk about their religion may differ significantly from the theological stances of that specific religion and the central dogma that it gravitates around. So, I think that I would imagine that even when it comes to mythology, you would probably find that people would engage with those entities or deities in a very different way. I would guess that compared to what the mythology says, I was thinking about the theogony for some reason.

So yeah, and what about the Puca, which, for some reason, I find interesting? I didn’t know that Puca was a thing until Dr Jenny Butler told me – you’re probably familiar with her work – and she was the first one to tell me, “Did you know that your surname is Irish?” Because it’s funny because, in Italian, it doesn’t mean anything at all. Then I found out that in Ireland, they have the Puca Festival; it’s spelt exactly the same way. I know that in English Folklore, there is also the Pooka, which is spelt a bit differently, but I just thought it was very interesting because, in Italian, it doesn’t mean anything. so at least it does mean something in other languages, so yeah could you tell us something about the Puca.

Icy: The Puca is really interesting because, again, I guarantee anyone in northern Europe, in particular, will have a version in their Folklore. It just may not necessarily have the same name. Obviously, I think pretty much all of the British Isles, and then plus the Channel Islands, all have a version, and I mean, I would argue that the most famous kind of example of one that people may have come across is in The Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Angela: Shakespeare.

Icy: And yeah, and Shakespeare is brilliant for Folklore, he really is, and a lot of the time you can kind of go, “Did this thing mean anything to people?” Well, it’s in Shakespeare, so it must have done, and he’s really good at kind of providing a record. Chaucer is good for the same as well. But with the Puca, I think they’re so fascinating because they have that shape-shifting element. I think shapeshifters are always fascinating because it’s that sense of not being able to trust what you’re looking at. But again, they’ve got that sense of… I can’t really think off the top of my head of many stories of them where they’re actively malevolent. Again, they tend to be mischievous, so they’ll do something because they find it funny. So if a particularly famous one that they’d like to do, they’ll take the form of a horse, much like a Kelpie, but where the similarity ends. The Puca will take someone for a ride, and then, just at random, they’ll disappear, and then the person will basically be left on the ground, not sitting on the horse that they thought they were riding.

And we have one in the Northeast called the Headley Kow, spelt k-o-w, and while that’s not referred to specifically as a Pooka by a lot of the sources, it clearly is. Because one of his favourite tricks was taking the form of a horse and then dumping people, usually into muddy puddles, and I always think there’s just such a four-year-old kind of idea of fun. And there’s just something about the words that are very slapstick, and their intention is not to harm. People don’t get hurt through their pranks – but the Pooka has obviously had a bit of a giggle. And then there are some stories where Pookas are actually quite helpful, and they pass on warnings to humans. So I kind of feel like they’re such interesting characters because there’s so much to them. And it does vary depending on which Pooka you’re looking at, but because they’re not actively enacting harm on anyone. Again, they’re just having a laugh at our expense. I sort of feel like they’re a little bit like the trickster archetype but with a bit more anarchy in there. And I sort of feel like there are so many of them, in so many different guises, making me think that people must have been encountering something. Because, you know, it would be a weird thing to try and rationalize otherwise; like, imagine you came home and someone said, “Why have you got mud on your trousers?” For a grown person to say, “Oh well, I found this horse, and then it disappeared under us, and I landed in a puddle.” Most people would say he tripped and fell. So, I feel like something must have been going on. So whether there are still Pookas out there and we’re just not encountering them because we’re in like cars and joints and stuff, I don’t know. But I love the idea that they’re still just pottering about the countryside, waiting for somebody to prank.

Angela: Or moving to the UK like me. I mean, people in the chat are making jokes about that. Oh yeah, that’s funny. So yeah, could you give us other examples of other-worldly beings in English Folklore, the Folklore that you have studied?

Icy: Just in general, or shapeshifters specifically?

Angela: In general, but you can elaborate on shapeshifters, definitely.

Icy: I think probably one of my personal favourites, and it kind of actually satisfies both criteria, is the Selkie.

Angela: The Selkie?

Icy: They pop up mostly around the Orkneys, but you do get them in Ireland as well, but also in places like the Faroe Islands. I think there are some Norwegian ones and also around Iceland. There are stories of people who are believed to be able – or not people actually – but could take the form of seals in the water, and then they could take off their seal skin and take the form of a human on land. Some of the stories vary. Sometimes, they could only do this once a year, Midsummer’s Eve being a big one. Because you tend to get dates like Midsummer’s Eve becomes really popular and for a lot of Folklore. And other times, it’s just they kind of come up onto the land because maybe they want to have a bit they seem to be really fond of dancing, and there’s just something really joyful about the idea that you’ve got these sort of seal-like creatures that live in the sea, but then they all want to have a bit of a boogie so they come up onto the land.

The downside for the female Selkies is that human men would often take a fancy to them and steal their skin so they couldn’t turn back into their true form and would then force them into marriage and so on. And there are some communities who would obviously kind of claim Selkie ancestry from some distant, distant past or whatever. And then there are some of the stories where once the Selkie wife finds her skin, she then returns to the sea. Sometimes, she takes any children with her; sometimes, she doesn’t. And then there was one really nice one where, even though the marriage didn’t really start under consensual terms, there must have been some kind of regard between them because the husband is out fishing at sea, and his boat gets into trouble. When the wife realizes what’s happening, she puts her skin on, and she goes out and rescues him. But because of that, she can’t return to the land again for seven years. So she has to give up her marriage more or less to save our husband. And you sort of think he couldn’t have been that bad if she’d saved him.

But then the male Selkies are really interesting because they’re completely at the other end of the spectrum. Male Selkies really like seducing human women, which sounds bad, but they kind of waited almost until they were called. So you could actually call one by shedding seven tears into the sea, and apparently, dissatisfied wives were big fans of male Selkies. And sometimes people used to use them as excuses – why the wife had left them because they’d run off with a Selkie. But male Selkies do seem to just kind of do their own kind of thing. And then they’re like, “Oh, I quite like her.” And then, you know, give the woman a good time and then just disappear again. But there’s an air of sort of fun about them. But because it sort of feels like they are fulfilling a need for the dissatisfied wife, in a way, you sort of get the feeling that the male Selkies, A, they’ve kind of been used as an excuse by rubbish husbands, but B, I think there’s a degree where they respect the woman’s set of desires or whatever in a way that the husband maybe doesn’t. So, male Selkies are really interesting compared to females. In these cases, they seem quite positive.

Angela: I wondered whether there was a way of hiding an affair because they were running away with somebody else rather than the Selkie.

Icy: Yeah, it probably sounded better to say that your wife would run off with Selkie than to say that she had run off with your neighbour or something.

Angela: Well, it seems fair enough if they were dissatisfied with their husband.

[Laughter]

But yeah, I actually never heard of the Selkie, so that’s really interesting. So, do you think that there is something similar to the idea of the Incubus and Succubus because of the sexual element? I’m not sure whether there is a sexual element, though, because if women were dissatisfied and were calling upon the male Selkie, would it mean that they would be satisfied by calling upon this spirit? Would it be sexual satisfaction or just forgetting about sex?

Icy: It sounds like it probably would, but I think the other way around because the human male is very actively seeking out the Selkie.

Angela: I’m sorry this one made me laugh; a nice way to give you performance anxiety.

[Laughter]

Icy: I think for the female Selkie, you also get these stories all over the world as well, and the type of creature changes. So you get Swan Maidens – which appear in Irish lore. There’s a bird woman in Papua New Guinea, whether they take the form of, I want to say, cassowaries, but I could be wrong. So you get these kinds of stories worldwide, and it’s very much an idea of unlike; I’m trying to remember which way around it is; the Succubus is the one that attacks men, isn’t it?

Angela: Yes.

Icy: Yeah, I always get them the wrong way around, and I have to work off the band Incubus to remember which is the male.

Angela: Yeah, the Incubus, I think it’s the male, and the Succubus is the female.

Icy: So with those, I get the feeling you don’t really get any choice in the matter if one comes to visit you, whereas obviously, when the human men choose Selkies, they actively go out and pick the one that they want, which sounds horrible because it is. So I think there’s a bit more human agency involved, and those kinds of stories.

Angela: And in the case of men, they are unsatisfied; it’s not why they seek out the female Selkie.

Icy: Sometimes, it kind of seems like they’re just kind of they usually see them first, so they’ve seen that particular one on the beach, and they’re like, that’s the one that I want. So it often sort of seems a little bit like they’ve just got their eye on someone and decided that’s the one for me – regardless of what she thinks about it. You don’t hear stories of them befriending the Selkie and wooing the Selkie. It’s just I’m gonna steal her skin, and then she has to marry me, and you’re just like, “Ew, that’s not really a good start for anything, is it?” So yeah, I think there’s always a domination element there, I think, more than anything else.

Angela: Yeah, that’s very interesting. Any other examples of other-worldly beings? Because this is very fascinating to me.

Icy: The other one I think I always pick just because I’m kind of biased because, again, it’s another one where I am. But you get them all over the North of England, and I think you also get them in other places. I’m sure Wales has them, but they’ve just got a different name. And that’s the Barghest – they’re also sometimes called the Pad-Foot, and they get mixed up with Black Dog Folklore quite a lot because they traditionally take the form of a black dog. And they’re interesting because, again, they can sometimes be quite mischievous. So there’s a story of one in Yorkshire, and it basically follows this guy home. But, like every time he turns around, it’s not there, but he can hear it behind him, and it even gets home before him. And then it just kind of lies across his front door sort of thing but then disappears when his wife’s coming because it’s obviously scared of his wife. And again, it doesn’t hurt this guy at any point. He does point out that he was leaving the pub when he saw this, and he stresses how much he wasn’t drunk. See, you do have to kind of go, “Were you a little bit drunk?” But then the story is quite a long one. But again, at no point does the Barghest hurt him, and it just kind of plays a couple of tricks on him and just freaks him out a little bit.

And then you get other ones where if someone notable in the village had died, it would lead a parade, like a funeral procession of all the dogs in the village and things like that. And generally, you just kind of let them get on with their thing because, if you interrupted them, if one of them struck you, you’d end up with a wound that would never heal.

But then, with some of the Barghest stories, people are like, “Oh, it can take the form of a black dog and a woman in white and a headless man on fire, and I’m like, how do you know they’re all the same thing? You know what I mean? So some of the stories are quite interesting. Sometimes, they are considered a death omen, sometimes not, and sometimes they just appear for lone Travelers. For example, sometimes they’ll accompany lone Travelers and act almost like guardians, particularly if they’re women. Other times, they just kind of push you into a wall and then wander off, which, again, is that sort of level of mischief that you get. Some of the other ones that I think are really interesting with them, and I mean Catherine Briggs, I think, she described them as being both a ghost and a goblin dog. So I think that they’re another one that sits in that weird intersection between ghosts and fairies, which makes you think, is there actually that much of a distinction between them?

Angela: Yeah, that’s interesting. We have a question from João, one of our moderators: Are sirens and Mermaids words for the same mythical creature, or are there stories that describe creatures with each name differently?

Icy: I’m so glad this one came up because this is a pet peeve of mine. Sirens, technically, if you want to split hairs, are very specific, and they relate; they basically appear in Homer’s Oddesy because Odysseus encounters them, and they are birds with the heads of women who lived on this particular island. Now, in some versions of the myth, there were Persephone’s handmaidens, and Demeter gives them wings to try and help find Persephone. And when they can’t, because, obviously, they don’t know that she’s in the Underworld, they end up banished to this island. And the Sirens, the one thing that they do have about them is they’ve got this beautiful singing voice, which is really sort of the thing that people know about sirens, and when they’re on this island, you tend to then find that a lot of ships are lured towards it by the sound of the singing. So, what Odysseus does is he has everybody on his ship stopper up their ears with wax. Then he has himself tied to the mast so he can hear it but without trying to direct the direction of the ship. Technically speaking, being able to hear the Sirens’ song and survive actually kills the Sirens. But that’s technically what Sirens are; they’re actually these human-headed birds with beautiful singing voices, and they get really hard done by in mythology, like they get treated really, really badly. At no point have they done anything wrong, but they just keep getting punished for stuff that’s out of their control, and people just remember them as luring sailors in. Nobody knows why their song did that. That one’s still, I think, open to interpretation.

Mermaids, on the other hand, appear in so many cultures – all around the world. So, they all have different motivations; they all have different sorts of living environments and things like that. But a translation error that somebody made led someone to conflict with Mermaids and Sirens. So the idea of Mermaids then singing on rocks to lure sailors actually came from that translation error. And it’s interesting because Mermaids if you look at them in Folklore. I mean, there’s one as a Mermaid story in Cornwall, and again, she’s given this beautiful singing voice, but she can take human form on land, and then she’s got the fishtail in water. And I think that is quite interesting because when you see all the churches, cathedrals, and things, they often have imagery of Mermaids; they nearly always have a mirror and a comb. And it’s to highlight how vain they are. So they’re usually a caution against sort of vanity and lust, and you know things like that. So, while a lot of people use the terms interchangeably now, technically speaking, they are actually two different types of creatures. Although I don’t know if I’d necessarily call Mermaids mythological because they appear in Folklore in many places, Sirens come from Greek mythology.

Angela: So they are different entities then, that’s the answer. What about the ghosts, then? I know that you are working on them for your PhD but more in film studies. But in terms of Folklore, what can you tell us about ghosts, the different types of ghosts and their beliefs, even their practices?

Icy: The ghosts are interesting because they change over time and almost become whatever the society that produces them needs them to be. And if you look at the first kind of recorded ghost story is the one, I want to say it’s Pliny the younger writes this one down, and it’s about this guy who keeps hearing a ghost sort of like, well, he keeps hearing rattling chains in his house and one day he eventually follows the figure, and there’s this guy just like pointing it a spot. So the guy actually has it dug up and then discovers a skeleton, and they have the skeleton buried properly, and then the haunting ceases. So it’s kind of like one of those Restless Spirits can’t rest until they’re they’re interred properly kind of stories, and you see that one time and again. Though I guess it’s sort of Folklore, it also appears in popular culture.

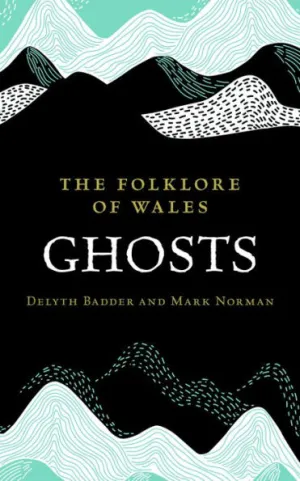

Most Victorian writers have had a crack at writing ghost stories at some stage, and you end up with this idea: there’s a long history of twinning the ghost story with the detective story. But then you also have the ghosts who come back with unfinished business or can’t leave until something is done. There’s a really strange strand of ghost stories, and I know it’s in the Welsh tradition because of Delyth Badder and Mark Norman’s forthcoming book about Welsh ghosts. I know this is also a thing in the Northeast as well. Like the person who buries treasure and then dies before they can tell anyone where it is. They’ll come back as a ghost and more or less guide people of the treasure, and they can’t move on until they’ve sort of handed it over, which is a a really bizarre one that doesn’t seem to have lasted in the same way. But yeah, then, of course, it leads to all kinds of really interesting stories, like the famous one with Red Barn murders, where a woman was murdered and buried in the barn. And then her stepmother started claiming to be dreaming about ghosts and things, and it sort of led to this huge sensation and this huge interest in ghosts as then seeking Justice for whatever had happened to them. So yeah, there’s a whole gamut of things that ghosts represent depending on at which point in time you’re looking at them.

Angela: And what about haunted houses? How has that changed over time – if you look at it in your study?

Icy: I mean, I would say that they’ve changed, obviously, because I’m just looking at from 1979 onwards. Even then, they’ve changed because, if you look at the film, we’ll look at films in general because that’s probably easier. But if you look at the films from the ’60s, it’s all about whether the house is actually haunted. Or is the character just having some kind of psychiatric episode? And then earlier ones, like “The Ghost Goes West,” the ghost is played for laughs like it’s a comedy type. And often, the house is like a big old rambling, like probably Gothic house. And then obviously, over time, that then becomes like a suburban house or an apartment and so on. And it kind of starts becoming like where ordinary people might encounter them. Obviously, you’ve got notable examples as I guess, to an extent, you could call “The Shining” a haunted house story. It’s just that the house is a whopping great hotel.

But I think part of the thing again with haunted houses is if you look at how they even appear in Folklore. Sometimes, somebody comes in and has to right a previous wrong because they’ve discovered something in the house that relates to a previous crime. Other times, you know, they’ve got some kind of link to the house that they need to reckon with. So there’s almost a therapeutic aspect, I think, to the haunted house in particular.

I mean, in the films I’m looking at, a lot of the time, they appear at points when there’s an issue with the economy, which sounds weird, but Rebecca Duncan talks about how you can use the Gothic as a barometer for how well the economy is doing.

Angela: What, I have never heard of it. Tell me more.

Icy: It talks about the way that, like, the gothic sort of charts economic turbulence, I think she puts it, and it’s really interesting because you look at a lot of the films, and you do sort of notice that they kind of disappear to an extent, at times when people feel relatively secure. And then they reappear when people feel a little bit more, “Ooh, not quite sure what’s going on.” So you get these points throughout time where these films become really, really popular. Obviously, this is also the aspect that Hollywood sees something that did well, and it’ll just do it to death, but in general, the films do sort of correspond to moments where there’s been some kind of issue. I think it was Stephen King who referred to the Amityville Horror as being the first economic horror. Where the fact that they can’t leave the house is because all the money’s tied up in it because they’ve bought it at auction. But still, too… No, they haven’t bought it at auction; they bought a rock-down price because of the murders that were committed there, but they still can’t leave when everything kicks off. It’s that idea that you’re tied to this property that you cannot leave. So that’s quite an interesting kind of strand, but that’s mostly American horror. I haven’t looked at horror elsewhere to see if that sort of plays out in other territories.

Angela: That’s very interesting. I’ve never heard of that. I’d be interested in looking more into the literature and the relation between the Gothic and economic instability. I’m just wondering whether it’s something that you can actually see or if it’s more something that, what’s the term? It’s sort of a confirmation bias where you’re trying to look at a reason, and you fish for one. I’m not sure, but yeah, I haven’t looked into that yet.

Icy: I think it’s one of those things with the films where, as I say, it can be really tempting to be like, “Oh, this happened like a year after so-and-such; it must be linked.” But then, at the same time, you’ve also got to bear in mind the fact that there’s all the time in pre-production before the film was ever thought of and conceived. And then, it was in production and then post-production. So sometimes it’s kind of like just because a film came out a year after something doesn’t necessarily mean it’s responding to it. Because sometimes it could have been in the works for a couple of years before the thing ever happened. So that’s why I’m so interested in the actual film making aspect of it because I’m sort of sitting there going, “Yeah, no, that’s literally just because of how long it takes to make a film; it’s not actually saying anything.

Angela: Yeah, I think it’s, yeah, these things are fascinating. It’s also always important to remember that correlation is not causation. So that’s why it’s not enough to see that certain things occur around the same time. You also need to find a causational link where you can claim that the two things are linked in a causal way. It is something that’s easy for me, sometimes, now that I’m claiming that people who have that then that put forward that argument are making this kind of mistake because I haven’t read anything about it. So, I’m just pointing out that it is something to consider when we look at arguments of any sort.

Icy: Yeah, I think, obviously, there’s way more to go into than I can here, but I think when you look at the gothic as a mode, even when it came out, it sort of comes out of a very particular point in time. And I think that it’s interesting, because when you look at a lot of the way the gothic develops, you can see some of it even related to the popular interest in things like collecting Folklore and people writing ghost stories and things. So, to me, they all kind of feed into each other in a way but probably not in a way that just an ordinary person in the street who was celebrating, like the Harvest Festival, for example, probably wasn’t interested in because this is the problem as well. You don’t want to start forcing, you know, your ideas about an economic change, like the Industrial Revolution, onto people, you know, without properly looking at all the moving parts to it.

Angela: Yeah, absolutely, and I was wondering if all these elements of Folklore that you have addressed so far, do you think that in contemporary paganism, these are reshaped in a different way compared to how they appear in Folklore? And is there a specific pattern that you can see in how things are reshaped in contemporary paganism?

Icy: I think the only thing that really sort of springs to mind is it’s not so much about them being reshaped. I think it’s more about them becoming almost fixed. So if somebody, for example, has, maybe they’ve got a family tradition, we’ll use that as an example. So someone’s got a family tradition for having a particular thing for a particular celebration. So you know a particular type of bread, for example, for Lamas or something like that. And that’s their tradition that comes from what they’ve always done or what their family has done for as long, as far back as it is necessary. But then, once people start to write about it, somebody else might never have spoken to them, so they might then look and look at Folklore and go, “Oh well, these people in the late 19th century did this, so that’s what all the people did.” And then, it gets written down and becomes fixed as the way to celebrate something or to honour something. And I think that is possibly just the drawback of writing things down. The minute that it then gets kind of written down and published, it sort of gets codified in a way that isn’t necessarily flexible enough to consider that that’s one snapshot from one moment in time.

So you get this with Folklore in general that you might share a practice that a particular set of people in a particular region had. But that’s only indicative of where that was collected. So even some of the Folklore from the Northeast, like I’ve got a couple of things that have been collected, in Newcastle itself, but you can’t guarantee that that was also the case in Sunderland, for example, which is technically just down the road. But some people might then expand that I would go, “Oh that, the whole of the Northeast did that.” And that, I think, is part of the potential pitfall, I’ll call it. Because it’s not a problem; it’s just something to be aware of. If you’ve got a family tradition for something and then you read in a book that this particular celebration or part of the wheel of the year or whatever requires this, but you actually go, my family does this, then it’s kind of like having that space to be able to go, “Well I’m going to stick to the family tradition, not what the book says.”

Using Folklore as a base is helpful, and I think it’s really good that people are looking to Folklore and so on. I think that’s also a case of remembering that you can be flexible with these things.

Angela: Yeah, I think the idea of codifying and also the idea that things become a bit prescriptive, especially on social media. I find that that is the case that often people tell each other, “Oh, this is the right way of doing this, or this is the right way of doing that, this is the true or the false.” You know that there are always these types of dichotomies in social media. So I think there is… definitely, I agree that there is an element of codification and being a bit prescriptive about what to do with things. I was also wondering, do you also feel like there is a romanticizing and perhaps even a sanitizing of certain elements of Folklore in contemporary paganism in the way they are Incorporated into the beliefs and practices?

Icy: I think there’s potential for that, depending on what the practice is. I think one thing that I find a little bit frustrating if that’s the right word, is when people – it’s not so much sanitizing – it’s more people who believe without questioning. So when you look at Folklore or just history itself and look at, for example, the way that witches are traditionally presented and how they were treated and things like that. But people still persist and believe – that all of these were just women who were healers; they were midwives. And you kind of go, “That’s not actually the history; it doesn’t necessarily hold that up as being true.” And people will insist on continuing to believe a particular narrative that has been bandied about in, say, popular witchcraft books since the 70s or whatever. Because nobody’s ever interrogated where that came from and whether that was true. And then, because it just keeps getting repeated by each new generation, it almost creates this legend that people continue to perpetuate, regardless of whether it has any historical basis or not. And I don’t know how helpful that is, but I suppose one of the downsides that you’ve got in general is because paganism is not taught in the same way that other religions are. People have to find the information where they can, so obviously, you can’t expect people to vet all of their sources when they’re sort of picking up a book in their favourite bookshop or whatever or choosing who to follow on social media.

So I think it is difficult, but I think that’s possibly more a question of information literacy than a problem with Folklore or paganism itself. I think, just again, it comes back to that idea of the flexibility of updating your knowledge about something when you learn something new. So if you learn after reading a book or actually, witches weren’t necessarily how they’ve been portrayed, I’ll update what I know about that. And I think that would probably be a more useful mindset for people, that it’s okay to go, “Oh, I used to know this, but now I know that.” And it’s okay to know both of them so it’s that sense of having a both-and perspective rather than an either-or.

Angela: Yeah, I think that that’s one of the things that, even with my project, that in Angela’s Symposium, I want to highlight because, on one end, I could say, “Oh, you can follow my work because it’s based on academic peer-viewed scholarship.” But I think that is not what I want. I don’t want people to be dependent on me. I want people to understand that there is a certain methodology they can learn to tell themselves whether a source is reliable. I think that it’s way more important, to be honest, to understand the methodology, and I think something that is very, very simple is just looking at the sources. It’s something that people sometimes don’t think about, and now I have all of my friends being traumatized every time they say, “Oh, I’ve read this in the book.” And it’s like, what’s the source? Where did the author get that information? And they’re like, “Oh, I don’t know.” And obviously, if it’s a book that is experiential where the author, for instance, if they’re a practitioner – they, are sharing their view of things, that’s fine. I mean, that’s obviously understandable.

But you very often find books in the bookstores of people that are explaining to you entire cultures or how a certain tradition works. And they don’t provide any references. I mean, even saying I’ve learned this from a teacher and presenting what I’ve learned to you would be understandable. Of course, you take it with a big grain of salt because you know it’s just another person. But at least you know it’s information that you can consider, what’s the source, and you balance the information when you acquire it. However, I find that many books throw around things about, “Oh, this tradition works this way and this other way.” A real pet peeve of mine is when you find percentages, and it sounds like it comes from a survey, but there’s nothing mentioned as a reference. Like, “Oh, 70 per cent of women, for instance, believe this and that.” And there is no reference to the source. This happens, of course, on social media all the time, but I’ve also seen it happen in magazines, books, and blog articles. So that’s like a massive pet peeve of mine. I mean, it’s bad enough when you are delivering information without citing any sources whatsoever, but it’s even worse when you are presenting it as percentages as if it comes from a statistical study that you, of course, are not mentioning because you’re just making it up – because it just furthers whatever is your agenda.

So that really bothers me a lot. But I see that on social media all the time. So people, you know, if you follow people on social media that throw around percentages and numbers and information without telling you the source, I would strongly advise you to take it with not a massive grain of salt, but more like with all the salt that you have in your home [Laughter] kind of source. Yeah, I wouldn’t trust that kind of source.

Icy: Yeah, the whole lack of sources thing or when people present things, it’s like, “Oh, this is just accepted fact.” And I’m like, “Says who?” is one of my things.

Angela: Another pet peeve of mine is when people say, “Scholars believe that…” And then you have no mention of the scholars, no reference. It’s like, “Who are these scholars? Do they exist? Are they part of your imagination?” This is something that students do all the time, so it’s something that I see in students’ essays all the time. You know, “Scholars say,” “Scholars agree.” So when I see it online, it kind of triggers my lecturer side – marking students’ assignments. But yeah, I think it’s really important to get into the mindset where you check the sources, and that doesn’t mean it only needs to be a reliable academic source. I mean, as I said, it can also be something experiential; it comes from the experience of somebody as long as you say it, as long as you make it plain that it is your experience or is your interpretation, that’s fine. I just have a problem with people delivering things as if that’s the truth or the, you know, the agreed-upon knowledge, and then it’s not, and there is no reference to that. So that bothers me. Sorry, I just went off on a tangent.

Icy: It’s a good point, though; you do get this quite a lot. And I think one of the problems with Folklore is that it’s an oral tradition a lot of the time. So, you know, like, one of the advantages you get with Folklore and social media is somebody might say, “Oh, my gran always told me…” And then they’ll tell, “Cool, awesome, we know where that came from; we don’t know where she got it from, but we know where you got it from.” But yeah, I think because of the nature of Folklore, people are a little bit better at saying where they got the thing. It’s okay to say like the man in the Chip Shop said because that’s still part of Folklore, but I think with some of the paganism things that I’ve seen, some really highly questionable things in books. And there was one book I nearly threw across the room because I was like, well, that’s just completely wrong. It’s historically wrong, and I don’t understand how you came to that conclusion, but then when you looked in the back – no bibliography, no references, no further reading, no nothing. So, I have no idea where this woman got any of her information from or if it was just from Instagram slides.

Angela: Yeah, because it can very well be the case nowadays. This makes me laugh. Ray says, “Angela’s secretly grading YouTubers on their math.” Oh, yes. And then, “Dr Puca’s Italian-Fairy-Angel blood is boiling, and we love it!” Yeah, it boils when there are no references.

Icy: Well, that’s the big thing. I always make sure I do. Like, I always have my list of references at the end of a blog post. And, like, I just did a book for DK, and there are no references, but I’d still say where something came from in the text itself. So I still name the people because, obviously, it’s a different kind of market; it’s not an academic book. But I’ll put the references on for two reasons: one is so I’m like, this is where it came from, and two is if someone’s really interested in the topic, they can then, like, they’ve now got extra sources that they can then go and have a look at. So it’s kind of like rather than someone having to say where should I start, there you go, there’s a whole reading list – have fun. And I think it’s not that hard to do. You might not necessarily want to use Harvard referencing, but even just a name in the book would be helpful.

Angela: Yeah, it’s not hard to do if you actually read books for your information; what else if you’re making stuff up? Of course, it’s gonna be difficult to mention your sources. You can tell that it’s a pet peeve of mine, and yes, this is another thing Zachary, “studies show,” and “it’s common sense” without mentioning studies.

Unfortunately, it’s very common on social media, but the fact that I also found it invokes it is appalling, in my opinion. I remember very clearly that my best friend was showing me a book on, I think it was – he’s very passionate about Afro-Brazilian traditions and this book, I think, was on Umbanda. You know, I was just going through the book, and you know, there was all the explanation of all the parts of the traditions and all the deities and all. And there was no reference, no bibliography, nothing, and it’s like, so where is this author getting all of this? Has he dreamed it? Has he hallucinated it? As it just, you know, when they woke up and said, “Oh yeah, let me just, and obviously, I am not particularly knowledgeable on that subject. So I couldn’t tell whether the information was accurate, but just the sheer fact that there was no source. For me, it was already a no-no.

Icy: I mean, it’s not too bad if someone’s at least got like a recommended reading list because you kind of feel like they’ve looked at something, but yeah, I think this is one of the things that I sort of find with some of the some, not all, some of the contemporary paganism is the fact that at least some authors will say this comes from my practice. This is how I do it; this is my experience. Here you go, do what you want with it. And I’ve actually kind of got a bit more respect for that approach because of the fact that they’re saying, “This is literally what I do.” To me, that’s not really that different from cookbooks and things. Whereas, yeah, when people are trying to then give like the historical section, and there are no references, and I’m like a casual Wikipedia search would show that a lot of that is wrong, so yeah, that’s always better.

Angela: And Wikipedia does better because it actually has sources. And Arcane Whisker says, “Dreams are technically a primary source.” Yeah, that’s a good point, but as I said, I’m not against these types of things. For me, it’s just about mentioning where the information comes from so that people can have a proper assessment. Yeah, so sorry about the tangent.

Icy: That’s fine.

Angela: Just you know, you know, talking about sources, it just triggers me. So, is there anything else that you would like my audience to know about the subject of today’s episode that I interviewed you about before we wrap up?

Icy: I genuinely think that people can get something out of Folklore; however, they choose to approach it, and I say that because I once asked on Twitter. You know how you sometimes ask a random question that ends up taking off, and I ask people like, what brought you to Folklore? And the answers were really interesting. And I did actually categorize them into sort of like different types, and some people were brought to Folklore by the fact that, like, a parent might have told them the stories from like their culture or whatever, as a child, which was really lovely. Or other people have just always been interested, you know, how some kids find a thing really early on, and then that’s the thing – that will be me. They just always really loved it but didn’t necessarily know it had a name. But the one that really, really stuck out to me was the people who found it helped connect them to a sense of place. So whenever they went anywhere new, they would make it their business to like to go and learn some of the Folklore about that place because then they felt when they got there that they had a bit more of a feel for the personality of the place rather than just like what TripAdvisor said. And this sort of felt more comfortable in that place because they were aware of its Folklore. Because I suppose, in some ways, Folklore is kind of a little bit like a form of cultural memory for a place.

So I think that’s where I genuinely think that everybody can get something out of Folklore, even if it’s looking at where you live or where you’re from. I mean, obviously, I’m fortunate that I live where I’m from, but I’ve got such a stronger connection to where I’m from because I’ve obviously taken the time to read its history and learn its Folklore and so on. And I know when I lived in London, it was the same – I’m such a geek – I used to go off on little history walks around the area and kind of get to know, again, the stories, and there’s so many weird things going on in London that I like. There’s something unusual pretty much everywhere, but it just made you feel more rooted in that place. So I think that would be my thing, that I think everybody can take something away from Folklore because it connects you into that, and it connects you to other people as well. So it’s things like asking your elderly relatives about things that they used to do when they were younger, asking them for family recipes, and so on.

Because it all just becomes a really interesting way of getting in touch with that information, it’s pertinent to you, and because Folklore includes family traditions, I think it’s a really nice way. And, obviously, a family can be a found family, you know, it can be an adopted family; it doesn’t have to be blood relations but just the people you want to connect with. You know, it’s sort of like learning about their traditions and so on. Again, it can be a really nice, easy way, in a fun way. I think in some ways, particularly if it involves food of getting to know how stories and people intersect.

Angela: Yeah, that’s a good point. From the way you’re saying it, it sounds like getting interested in the Folklore of the place you live in makes you connect with its spirits.

Icy: Very much so.

Angela: Sounds like a nice note to end our interview. So where can people find you, Icy?

Icy: Oh, I’m on almost every social media platform, including all the new ones that no one fully knows how to use yet, as usually @IcySedgwick. Or, obviously, my website is icysedgwick.com. I’ve got my podcast, “Fabulous Folklore,” which is on pretty much as many platforms as I can think of, or just good old-fashioned YouTube, and you can subscribe there, and it will then notify you every time I put an episode up. So I’m basically everywhere in a really annoying kind of way, I think, for some people.

Angela: It’s better to annoy people with Folklore than with information without references!

[Laughter]

So, thank you so much.

Icy: I’m going to come off this, and I’m going to go through my entire PhD bibliography to check it now.

[Laughter]

Angela: I’m sorry. I hope that you know it wasn’t meant like that, but it’s just a pet peeve of mine, and I can’t help it. Thank you so much for being here, Icy. I recommend everybody check out her Fabulous Folklore podcast.

Icy: Thank you very much. It’s been lovely being here.

Angela: Thank you again. So, thank you all so much for having participated in this interview. Whether you’re watching this live, or you’re watching it afterwards, and if you, of course, liked this interview, please don’t forget to SMASH the like button, subscribe to the channel if you haven’t already, and hit the notification Bell because otherwise, YouTube might not notify you when I upload a new video. Also, leave me a comment so that I know what you thought about the interview and whether you have any questions. And also, remember that the best way to be in contact with me if you want to communicate with me more because I tend to get quite a few messages from you guys, which is fantastic, but I really interact only with my patrons, so if you want to have a longer type of interaction with me I would really recommend to become become a patron or a supporter any type of support really would get you access to getting in contact with me and having a conversation with me if that’s what you what you’re interested in so thank you all for being here and stay tuned for all the academic fun.

Bye for now.

Social media @icysedgwick

First streamed 11 Sep 2023