Hello, symposiasts. I’m Dr. Angela Puca, a religious studies PhD, and this is your online resource for the academic study of magic, esotericism, Paganism, Shamanism, and all things occult. Today, we have something special: an interview with Peter J. Carroll. He was not quite — I wouldn’t say the founder of Chaos Magick — but one of the most influential figures in Chaos Magick. I think that the way people understand Chaos Magick now is probably primarily shaped by Peter J. Carroll. So, I asked him 15 questions. But before we dive in, I’d like to do some housekeeping, as we could say.

First of all, as you know, this is an interview with Peter J. Carroll, and these are some of the books that he has written. Before we start, I want to remind you to sign up for my newsletter. This way, you don’t have to rely on the inconsistent algorithm and social media platforms that might shut down whenever they decide or be bought by Elon Musk. By signing up for my newsletter, you will always be up to date with everything that is going on with me, with my work – my personal and academic insights, and you will be part of my community regardless of social media platforms. So, please do that. You will find all the links I will describe in the description box and later in a pinned comment.

Also, this project is brought to you by you. So, if you want me to keep going with this project and if you have the means, please consider supporting my work with a one-off PayPal donation by joining Memberships, Patreon, Ko-Fi, or by sending super chats since this is a live stream. You will find all the ways in the description box as well.

So, we can start now. First, I must tell you the story of how this interview happened. Peter and I have friends in common. I asked him whether he’d be willing to be on my channel and be interviewed for Angela’s Symposium. Peter was keen on doing that. But, if you know Peter J. Carroll, he’s not somebody who likes to show up in person. So, it worked: I sent him the questions, he sent me back the answers, and I will read them to you.

So this is a since this is a a different format from typical interviews that you see on Angela Symposium I thought how I could could make it a little bit more exciting and engaging and so the way I thought of going about this is to of course read you his answers well the questions that I asked some of which come from you guys by the way because as you know I sent out in my newsletter a request for you to send your questions and I did the same on my patreon my coffee and my membership program on YouTube so I could see that there were some patterns in your questions obviously lots of you asked different questions but I put them together I tried to identifi patterns and hopefully these questions will make everybody happy but stay tuned because and this is also going to be quite long and a deep dive so grab a snack grab a drink possibly not alcoholic because you will need all your all your faculties to follow along and as soon as I can I will reply to your questions so because it’s difficult for me to to juggle everything but if you want to make sure that your question is going to get answered please send it as a super chat so I guess that we can start and also I thank you oh Hank says nice cup of hot chocolate thank you Hank.

And I saw another Super Chat. I will answer that later. So, yeah, I guess let’s start with the questions.

Since this is a different format from the typical interviews you see on Angela’s Symposium, I thought about how to make it more interesting and engaging. The way I thought of going about this is to read you his answers and the questions that I asked, some of which come from you guys. Because as you know, I sent out a request for you to send your questions in my newsletter. I did the same on my Patreon, Ko-Fi, and YouTube membership program. I could see that there were some patterns in your questions. Obviously, lots of you asked different questions, but I put them together and tried to identify patterns, and hopefully, these questions will make everybody happy.

So, the first question that I asked Peter Carroll was about the evolution of Chaos Magick.

How have you seen Chaos Magick evolve since its inception, and what, in your opinion, accounts for its increasing popularity in contemporary occult practices?

It all began back in the 1970s with small groups meeting in people’s flats and houses, with handmade magazines sold by mail order or in occult shops and with a few books either self-published or rather amateurishly published by small new independent publishers. We had a great deal of debate and argument about the nature of Chaos, what types of magic seemed the most effective, the relative merits of the approaches of Aleister Crowley and Austin Spare, and, of course, the underlying metaphysics and science, and the accompanying art and music.

A second phase followed after proper commercial publication of the early books and the beginning of public lectures and seminars, and the establishment of the IOT annual general meetings and local temples in various cities around the world. During this phase, many more books became written, some rather derivative, some highly innovative, and groups and individuals developed hundreds of new experimental rituals and practices.

A third phase began after two things happened. Firstly, the paradoxes and contradictions of ‘organised chaos’ and ‘institutionalised individualism’ boiled over within the chaos magic groups (particularly the IOT) that had formed. Secondly, the internet became widely and easily available for personal use, and groups and individuals started establishing forums and websites offering a cornucopia of chaos magic interpretations and applications, and much of the socialisation that had taken place in groups, meetings and workshops declined in favour of electronic communication. The insights of chaos magic seem to have seeped into a wide variety of other esoteric traditions, including modern Witchcraft and Hermetics, Neo-Paganism and Neo-Shamanism.

Now, let’s look at my commentary. So the way this will work is that I will read you the answer by Peter J Carroll. Then, I will give you my academic commentary, commenting on Peter J Carroll’s answer. I put it into the context of academic scholarship and academic discourse, and the research that is going on every one of my commentaries has a list of references. Still, it was too long to put in the description box, so you will find the final slides where I mentioned the references for each commentary. You will also find the full transcript of this interview and my commentary on my Patron at the Initiate and higher levels. Let’s start with the first commentary on the evolution of Chaos Magick.

So, Peter J. Carroll’s response provides a valuable historical and sociological framework for understanding the evolution of Chaos Magick, a contemporary magical tradition that emerged in the 1970s. Carroll identifies three distinct phases in its development, each marked by shifts in media, community structure, and intellectual focus.

So, as you can see from his answer, phase one is the grassroots beginnings. Carroll’s account of the early days of Chaos Magick evokes a grassroots movement characterised by small gatherings in private homes and the circulation of handmade magazines. This phase can be seen as a form of “vernacular religion,” a term used by scholars like Leonard Primiano to describe religious expressions that emerge organically within communities (Primiano, 1995). The debates and arguments that Carroll mentions—concerning the nature of Chaos, the efficacy of different magical techniques, and the influences of Aleister Crowley and Austin Spare—reflect a community in the process of self-definition. This phase also highlights the DIY ethos prevalent in many new religious movements, as noted by scholars like Christopher Partridge (Partridge, 2004).

Phase two can be called institutionalisation and expansion. This second phase is marked by commercial publication and the establishment of the Illuminates of Thanateros (IOT), representing a move towards institutionalisation. Carroll’s mention of “annual general meetings and local temples” suggests a formalisation of practice and community structure. This phase resonates with what sociologist Rodney Stark describes as the “churching” of religious movements, a process through which they gain social capital and legitimacy (Stark, 1996).

However, Carroll also notes the emergence of derivative works and innovative rituals, indicating a tension between institutional stability and individual creativity, a dynamic observed in many esoteric traditions that we don’t just see in Chaos Magick in many esoteric traditions indeed (Hanegraaff, 1996).

And then the third phase is the digital disruption we could call it because it is marked by the advent of the internet, which Carroll describes as both a boon and a challenge. On the one hand, the internet facilitated the dissemination of Chaos Magick across various esoteric traditions, from modern Witchcraft to Neo-Shamanism. On the other hand, it led to a decline in face-to-face socialisation. This reflects broader academic discussions about the “deterritorialisation” of religion in the digital age, as explored by scholars like Heidi Campbell (Campbell, 2012). The internet has allowed for a proliferation of interpretations and practices but has also raised questions about the depth and authenticity of online religious engagement.

Carroll’s narrative offers a microcosm of broader trends in contemporary religion and spirituality: the tension between grassroots innovation and institutionalisation and the transformative impact of digital technology. It also raises intriguing questions for further research, such as the role of Chaos Magick in the broader landscape of contemporary esotericism and the impact of its principles on other magical traditions.

Now, let’s go to the second question. The second question is on the role of gnosis and altered state, and my question to Peter Carroll was,

In your work, you’ve emphasised the role of ‘gnosis’ or altered states of consciousness. Have your views on its importance shifted over time, particularly in light of new counter-currents in occultism?

And Peter answered,

In Chaos Magic we use the word Gnosis to specify the altered state(s) of mind used in mysticism and magic rather than the particular contents or revelations or beliefs associated with mystical or magical activity. Gnosis covers a wide spectrum from inhibitory to excitatory states of mind attainable by many means from quiescent meditation and concentration to ecstatic dancing. Thus, we regard the attaining of Gnosis as a technical practical procedure, not as a validation of any particular belief or mystical enlightenment. Perhaps even more controversially Chaos Magic asserts that we should regard beliefs as tools rather than as ends in themselves, and that we should evaluate them on the basis of their effectiveness (as scientists do).

Of course, many people become attracted to occult, mystical, cultish, and religious ideologies because they want to really believe in something they can regard as ‘really true’ both despite and because of its contra-intuitiveness and irrationality. Thus, Chaos Magic remains perpetually at war with systems of ‘true beliefs’ such as Thelema-Crowleyanity, Monotheistic religions, and conspiracy theories.

However, you pronounce it now. Let’s go to my commentary on this answer.

So, let’s look at ‘gnosis’ as a “technical, practical procedure” rather than a validation of particular beliefs or mystical enlightenment is noteworthy. This perspective aligns with what scholars like Tanya Luhrmann have observed in modern magical practices, where the focus is often on the efficacy of techniques rather than the veracity of metaphysical claims (Luhrmann, 1989). Carroll’s view also resonates with the ‘instrumental rationality’ that Max Weber identified as characteristic of modernity, where actions are evaluated based on their effectiveness in achieving specific goals (Weber, 1978).

The idea that beliefs should be regarded as tools rather than ends in themselves is a provocative stance that challenges conventional religious and esoteric systems. This echoes the ‘bricolage’ approach to spirituality described by scholars like Wade Clark Roof, where individuals construct their own systems of meaning by borrowing elements from various traditions (Roof, 1999). Carroll’s assertion that beliefs should be evaluated based on their effectiveness also aligns with the pragmatic approach to religion and spirituality advocated by William James (James, 1902).

Carroll’s statement that Chaos Magick is “perpetually at war with systems of ‘true beliefs'” such as Thelema and monotheistic religions highlights the tension between Chaos Magick and more dogmatic systems. This reflects broader academic discussions about the ‘orthodox’ and ‘heterodox’ in religious studies, as explored by scholars like Talal Asad (Asad, 1993). The conflict also underscores the epistemological challenges inherent in studying esoteric and mystical traditions, as noted by scholars like Wouter Hanegraaff (Hanegraaff, 1996).

So it’s interesting because Carroll’s views on ‘gnosis’ and altered states in Chaos Magick offer a lens through which to examine broader trends and tensions in contemporary spirituality and esotericism. His emphasis on technique over truth and effectiveness over dogma challenges traditional paradigms and invites further scholarly inquiry into the evolving landscape of belief and practice in modern magical traditions.

Now, let’s move on to the next question: technology and Chaos Magic. My question to Peter was,

Considering Arthur C. Clarke’s 3rd Law, do you believe that advancements in technology, particularly artificial intelligence, will influence the future trajectory of Chaos Magick?

And hold on because I thought this answer was quite brilliant.

Clarke’s third law, that “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic”, also probably applies the other way around as well if magic depends on physical principles that we barely understand yet, rather than on something ‘spiritual’ (In rational moods that word seems meaningless to me).

Programs already exist to draw tarot card spreads in response to questions and to make sigils automatically out of typed-in wishes, but I severely doubt the efficacy of such procedures unless the magician also puts a lot of concentration into the process.

Mobile telephones have not entirely replaced telepathy; allegedly, some magicians will telephone a target to strengthen a magical link and then attempt to cast a spell on the target whilst talking about something else entirely. To do this effectively seems like a challenging mental manoeuvre.

Artificial intelligence can do some of the things that magicians have traditionally evoked servitors and spirits to do. For the retrieval of ordinary information or perhaps for the rearrangement of concepts into a nice poetic incantation, they may have their uses, but presently, I wouldn’t rely on them for much beyond that.

We have a joke maxim in Chaos Magick that runs – make your own servitors, don’t play around with demons from grimoires, you don’t know where they’ve been.

He leaves it at that at that question, that final question. So, I will start with my commentary now so Peter J. Carroll’s reflections on the intersection of technology and Chaos Magick offer a nuanced perspective that engages with broader academic debates on the relationship between technology, spirituality, and human agency. This commentary aims to unpack Carroll’s views, situating them within the academic discourse on the sociology of religion, philosophy of technology, and the anthropology of magic.

So, as you can tell, Carol invokes Arthur C Clark’s Third Law, “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic,” to explore the porous boundary between technology and magical practice. This resonates with scholars like David J. Hess, who have examined the ways in which scientific and magical discourses often overlap and inform each other (Hess, 1993). Carroll’s suggestion that magic might also be a form of advanced technology awaiting scientific elucidation challenges conventional dichotomies between the ‘natural’ and the ‘supernatural,’ a topic of interest in the philosophy of science (Dupré, 1993).

Now, as for technology as an extension of magical practice. Carroll’s scepticism about the efficacy of automated tarot and sigil-making programs reflects a broader academic discussion about the role of human agency in religious and magical practices. Scholars like Birgit Meyer have explored how material objects become ‘powerful’ only when activated by human agents within specific ritual contexts (Meyer, 2015). Carroll’s point that “the magician also [needs to] put a lot of concentration into the process” aligns with this view, emphasizing the importance of human intentionality in magical efficacy.

And then we have artificial intelligence, which I thought was interesting. How it was compared to servitors or actually with demons that you can find in grimoires, the discussion about artificial intelligence or AI and, you know, its serving functions similar to magical servitors is particularly intriguing. Carroll’s cautionary stance—akin to the Chaos Magick maxim about making one’s own servitors—raises ethical and ontological questions about the agency of non-human entities, a topic explored by scholars in the field of Science and Technology Studies (Latour, 1993).

Then we have the cany nature of AI because Carroll’s musings on whether AI will ever display creativity or self-awareness touch on debates within the philosophy of mind and cognitive science. His scepticism reflects ongoing academic debates about machine consciousness and the ‘hard problem’ of consciousness, as discussed by scholars like David Chalmers (Chalmers, 1995).

Carroll’s reflections offer a rich tapestry for understanding the modern world’s complex interplay between technology and spirituality. His views challenge us to think critically about the boundaries we draw between science and magic, human and machine, and efficacy and belief. These intersections offer fertile ground for further academic inquiry into the evolving landscape of contemporary magical practices in a technologically mediated world.

Now let’s let’s move on to the next question, which is on the IOT the Illuminate of Thanatos. So I asked,

Could you delve into your motivations for co-founding IOT and how you perceive its relevance in the contemporary magical landscape?

And this is what Peter J Carroll answered:

I wanted to provide a structure for the discussion, development, and practice of chaos magic, and to this end, I offered a structure of grades and temples and simple outline rituals for people to build upon. Although the structure had neo-masonic elements to it, I intended the grade system to merely reflect experience expertise and organisational responsibility; I did not want to use the old ‘hidden masters’ or ‘secret wisdom’ ploys to create a cultish hierarchy. The resulting Magical Order worked very well for about five years; we had some amazing meetings, performed some extraordinarily creative experimental rituals, and developed a lot of further ideas like the Ouranian Barbaric language and the Eight Forms of Magic. As a result of these manically creative years, I wrote my second major treatise on magic- Liber Kaos.

Eventually, the ‘organised chaos’ initiative of the IOT ran into the problems of personal differences and squabbles over position within its structure, permissible directions for its future development, and the pressures of constant innovation. I retired from trying to lead it as I had a growing family and business and other research to attend to, and I had grown weary of disputes within it. I hear that it continues to operate but perhaps with much less of the creative fury than it once had.

Meanwhile, the ideas of chaos magic seem to have a widespread influence on how we regard and practise magic and occultism in the developed world. The basic ideas seem easily summarised: –

We can explain all occult and magical (and religious) phenomena using a lot of neuroscience and psychology and a bit of parapsychology.

All cultures have devised and redesigned their magical symbolism on a syncretic basis, and in recent times, each generation recreates it to taste and its desired application.

‘Spirits’ and ‘deities’ and ‘demons’ have primarily a subjective existence in proportion to our investment of belief in them, but they can also have objective effects via operator parapsychology.

The beginnings of such ideas seem implicit in works such as the late nineteenth-century Golden Dawn Corpus. Chaos magic simply made the principles completely explicit and replaced the Neoplatonist rationale for parapsychological effects with the idea that quantum physics could probably explain them. These new ideas have proved popular and influential in magic as the cultures of the developed world have advanced from a religious to a more scientific paradigm or worldview.

Now, my commentary on it: oh wow, this is darker than it looked on my computer. I’m sorry. [Fixed here]

So Peter J. Carroll’s reflections on the founding and evolution of the Illuminates of Thanateros (IOT) offer a compelling lens through which to examine the institutional dynamics of contemporary magical orders.

So I’m trying to unpack this as in all my academic commentaries in relation to the academic discourse, so Carroll’s account of the IOT’s initial years as a space for “extraordinarily creative experimental rituals” and the development of new magical languages and forms resonates with sociological studies on the charismatic phase of new religious movements (Weber, 1947). The eventual “problems of personal differences and squabbles” that Carroll describes align with what Rodney Stark and William Sims Bainbridge identify as the “routinisation” phase, where the charisma of the founding period gives way to institutional challenges (Stark & Bainbridge, 1985).

So it’s not just in relationships, but also in religious movements, you’ve got the honeymoon phase, and then things get more difficult about the neo-masonic structure and anti-hierarchical intent. Carroll’s decision to incorporate a grade system with “neo-masonic elements” without resorting to “hidden masters” or “secret wisdom” reflects a tension between structure and egalitarianism. This echoes Catherine Bell‘s work on ritual theory, which discusses how ritual forms can reinforce and challenge social hierarchies (Bell, 1992).

As for the chaos Magic’s epistemological shift, Carroll’s assertion that chaos magic has influenced a broader shift towards a more scientific paradigm in magical practice is noteworthy. This aligns with Tanya Luhrmann’s anthropological work on the “interpretive drift” in modern magical practices, where practitioners increasingly draw on scientific language to explain magical phenomena (Luhrmann, 1989).

And then we have syncretism and the subjective term; the emphasis on syncretism and the subjective nature of spirits and deities reflects broader trends in contemporary spirituality, as noted by scholars like Paul Heelas and Linda Woodhead in their study of the “spiritual revolution” (Heelas & Woodhead, 2005). Carroll’s focus on the role of belief and psychology in magical efficacy also resonates with the ‘subjective turn’ in religious studies, where individual experience and interiority are given analytical precedence (Taylor, 2002).

So I’m trying to unpack this as in all my academic commentaries in relation to the academic discourse, so Carroll’s account of the IOT’s initial years as a space for “extraordinarily creative experimental rituals” and the development of new magical languages and forms resonates with sociological studies on the charismatic phase of new religious movements (Weber, 1947). The eventual “problems of personal differences and squabbles” that Carroll describes align with what Rodney Stark and William Sims Bainbridge identify as the “routinisation” phase, where the charisma of the founding period gives way to institutional challenges (Stark & Bainbridge, 1985).

Also, Carroll’s reflections on the IOT and the evolution of chaos magic offer a rich case study for understanding the complexities of institutionalising esoteric practices. His account raises important questions about the tension between structure and innovation, the role of scientific discourse in contemporary magic, and the subjective turn in religious and magical practice. These insights contribute to ongoing academic dialogues on the changing landscape of contemporary spirituality and the challenges of institutionalising esoteric wisdom.

Now, let’s move on to the next question. So, the next question is on the hypersphere model and theories of time. So my question was,

With the Hypersphere model gaining traction, do you anticipate that your 3D-time hypothesis will also become more widely accepted?

Peter J Carroll answered hypersphere Cosmology stands as a purely scientific alternative interpretation of the data and observations that led to the development of the current mainstream concordance model – LCDM Big Bang Cosmology. I became increasingly suspicious of the official Big Bang theory and the increasingly strident assertions from conventional cosmologists that they ‘Know its Right’ despite its many problems, so I set myself the task of comprehensively reinterpreting the data and observations from which they cobbled together their interpretation.

So far, the Hypersphere Cosmology model remains unfalsified but unconfirmed, but if anything, the recent James Webb Space Telescope data tends to lend more support to it than it does to the Big Bang theory, as do the endless null results of experiments to confirm the existence of dark matter and dark energy by other means.

Intellectual curiosity and metaphysical dissatisfaction provided my motive for developing the Hypersphere Cosmology model. I did use some magical techniques in developing it, such as invoking ‘imaginary’ entities that might know the answer and various meditation techniques to provide inspired guesses worth checking out mathematically, but it remains a hard science hypothesis open to confirmation or falsification by mathematics and observational data. It does seem to offer a single ‘occult’ possibility – if the universe has a cyclic rather than a linear time structure, then advanced intelligence has effectively unlimited time in which to develop, and we may share it with aliens who have developed their intelligence over almost incomprehensibly vast timescales.

My speculations about three-dimensional time arise from a motivation to uncover a quantum mechanism for parapsychology, and this necessarily involves a consideration of the current limitations of quantum theories. The celebrated quantum physicist Richard Feynman quipped, ‘Nobody understands quantum physics’, and the situation has not improved since that quip. Plainly, we have missed something, probably many things. For the moment, I have settled on exploring the hypothesis that time has the same (but hidden) three-dimensionality as space. Work continues on the idea.

Now, my commentary, and I’m annoyed because my slides look different over here than on my computer. I’m so sorry anyway. These things always happen when you are live streaming, so Peter J. Carroll’s reflections on Hypersphere Cosmology offer an intriguing intersection between scientific inquiry and esoteric thought. This commentary aims to contextualise Carroll’s ideas within the broader academic landscape, touching upon the philosophy of science, the sociology of scientific knowledge, and the epistemology of esotericism.

This commentary that I’m doing aims to contextualise Carroll’s ideas within the broader academic landscape. Let’s start with the scientific descent and alternative cosmologies that were supposed to be here but unfortunately hidden. Thus, Carroll’s scepticism towards the mainstream Lambda-CDM Big Bang model echoes Thomas Kuhn‘s notion of scientific paradigms and the potential for paradigm shifts (Kuhn, 1962). Carroll positions Hypersphere Cosmology as an alternative interpretation that remains “unfalsified but unconfirmed,” a status that resonates with Karl Popper‘s philosophy of falsifiability as the demarcation criterion for scientific theories (Popper, 1959).

Then, we have historical techniques in scientific inquiry. The use of magical techniques, such as invoking ‘imaginary’ entities and meditation for “inspired guesses,” is particularly noteworthy. While unconventional in mainstream scientific discourse, this approach can be contextualised within the history of esotericism, where the boundaries between science and magic were historically more porous, as explored by scholars like Frances Yates (Yates, 1964).

Then we have the time quantum mechanics and parapsychology, which is supposed to be the last point, so Carroll’s exploration of three-dimensional time to uncover a “quantum mechanism for parapsychology” is an ambitious endeavour that challenges the limitations of current quantum theories. This recalls debates within the philosophy of science about the ‘interpretation problem’ in quantum mechanics (Bell, 1964).

Carroll’s Hypersphere Cosmology serves as a compelling case study in the sociology of scientific knowledge, illustrating how alternative cosmological models can emerge from a blend of scientific scepticism and esoteric techniques. His work also raises provocative questions about the potential for cross-fertilisation between scientific and esoteric epistemologies, particularly in areas where mainstream scientific models face challenges or limitations.

Now, let’s move on to the next question that I asked. So, the sixth question was about interconnectedness in Chaos Magick. I asked,

Can you elaborate on your understanding of the interconnectedness of all living beings and the environment within the framework of Chaos Magick, as discussed in “Liber Null”?

Peter replied, The more we learn about ecology, the more we understand about the subtle, causal interconnectedness of all life on earth. The more we learn about quantum physics, the more we come to suspect that even more subtle quantum entanglements may also interconnect all living beings to each other and to their environment.

So, as for my commentary… Oh, now it looks like it was looking on my computer. That’s great. So Peter J. Carroll’s brief but potent remarks on the interconnectedness of all living beings within the framework of Chaos Magick offer an intriguing confluence of ecological, quantum, and esoteric thought. This commentary aims to situate Carroll’s views within broader academic discussions on ecology, quantum theory, and the philosophy of interconnectedness.

So, let’s start with the ecology and esotericism. Carroll’s reference to ecology as a lens through which to understand the “subtle, causal interconnectedness of all life” resonates with a growing body of scholarship in religious studies and philosophy that explores ecological themes within esoteric and spiritual traditions (Albanese, 2007). The notion of interconnectedness is not new to esotericism but has found renewed relevance in current ecological crises.

Then, we have the quantum entanglement and esoteric thought. The invocation of quantum physics, particularly the concept of quantum entanglement, as a possible mechanism for a deeper level of interconnectedness is noteworthy. While quantum mechanics has been appropriated in various New Age and esoteric discourses, often in ways considered dubious by physicists, Carroll’s mention is more cautious, suggesting a “suspicion” rather than a claim (Stenger, 1990).

Then, we have interconnectedness as a philosophical and spiritual concept. The idea of interconnectedness has a long history in both Western and Eastern philosophies and spiritual traditions. From the holistic philosophies of ancient Greek thinkers like Heraclitus to Eastern spiritual concepts like Indra’s net, the notion that all things are deeply interconnected has been a recurring theme (McFarlane, 2002).

Carroll’s comments on interconnectedness within Chaos Magick serve as a microcosm of larger academic and philosophical discussions about the relationship between humans, the natural world, and possibly even the quantum realm. His views offer a snapshot of how contemporary esoteric practices can engage with scientific and ecological discourses, raising questions worthy of further academic exploration.

Now let’s move on to the next question, which is on digital media’s impact on Chaos Magick: get a snack and grab a drink. so my question was,

How has the emergence of digital platforms and cyberspace shaped the practice and perception of Chaos Magick?

And Peter replied,

It certainly seems to have encouraged people to work from home rather than meet up face to face for discussions and group workings in person. Whilst this allows some interaction with people from faraway places that could not easily occur otherwise, it has some serious downsides. Arguments and debates can descend into unproductive incivility under conditions of relative anonymity, and people can end up in a self-selected bubble of only those who agree with them. Plus, the awesome volume of instantly available information can result in people flitting from topic to topic with little in-depth consideration and a rapidly diminishing attention span. I prefer to treat my emails and posts as old-style postal letters; I will often think for a day before replying, compose a reply, and edit and post it the day after that.

So, now, on to my commentary on that. So Peter J. Carroll’s reflections on the impact of digital media on Chaos Magick offer a nuanced perspective that engages with broader academic discussions on the digital transformation of religious and esoteric practices.

First of all, Carroll’s observation that digital platforms have encouraged solitary practice over communal gatherings resonates with wider trends in religious studies. The concept of “digital religion” explores how religious and spiritual practices are being transformed by the internet and social media (Campbell, 2012). While digital platforms can facilitate global connections, they also risk diluting the communal aspects that often enrich spiritual practices.

Then, we have the anonymity and online discourse. Carroll’s concern about the “unproductive incivility” that can arise in online discussions due to anonymity is well-founded. Studies in psychology and communications have shown that the anonymity afforded by online platforms can sometimes lead to toxic behaviour and polarisation (Suler, 2004). This is particularly relevant for esoteric traditions like Chaos Magick, where debate and discussion are integral to the practice.

And then we have the information overload and the attention economy because, as we have seen, Carroll’s critique of the “awesome volume of instantly available information” leading to a lack of depth and a “rapidly diminishing attention span” taps into ongoing debates about the attention economy. Scholars like Nicholas Carr have argued that the internet is reshaping our cognitive processes, often at the cost of deep, focused thinking (Carr, 2010).

Carroll’s insights into the impact of digital media on Chaos Magick serve as a valuable case study for understanding the complexities of religious and esoteric practices in the digital age. His comments highlight both the opportunities and challenges that digital platforms pose, echoing broader academic concerns about how digitalisation affects human interaction, discourse, and cognitive processes.

And by the way, kudos to all of you Symposiasts because you’re sticking around, so you don’t have a short attention span. so good us to you, and I hope that my project counteracts this lack of depth in analysing information and also the attention span, although, of course, I’m also on TikTok and Instagram, which don’t really allow for in-depth analysis, but that’s why YouTube is my favourite social media to be honest because it allows us to go deep into topics and even stay on for hours.

So, let’s move on to the next question. This one is on the diverse opposition to Chaos Magick, so my question was,

Have you experienced more resistance from practitioners who adhere to specific magickal traditions compared to those who adopt a more eclectic approach?

Ha, yes, Chaos Magic has always duelled with Thelema-Crowleyanity, I guess that it is the type of Thelema that tends to lean more towards Crowley, Crowleyanity, and the OTO. Quite a few chaoists started as thelemites but came over to Chaoism because they grew tired of the rigid belief system of Thelema. At one point the OTO banned its temples from using Chaoist rituals and ideas. Some Wiccans refused to accept that their ‘tradition’ has no real history and consists entirely of a modern syncretism of occult ideas cobbled together very recently. Others embraced the freedom that insight brought and continued to evolve their ideas and ideology and practices to suit the times.

So, now, on to my commentary on this. Peter J. Carroll’s remarks on the opposition Chaos Magick has faced from practitioners of specific magical traditions like Thelema and Wicca offer a compelling lens to examine the dynamics of orthodoxy and heterodoxy within contemporary esotericism. This commentary aims to situate Carroll’s observations within broader academic discussions on religious exclusivism, syncretism, and the fluidity of esoteric traditions.

Carroll’s experience of resistance from Thelema and the Ordo Templi Orientis (OTO) highlights the tensions that often exist between esoteric traditions that have a more structured, dogmatic framework and those that adopt a more eclectic or anarchic approach, such as Chaos Magick. This is consistent with scholarly observations that religious exclusivism is not confined to mainstream religions but can also be found in esoteric and occult traditions (Hanegraaff, 1996).

Also, we have the about the syncretism and historical legitimacy of Wicca. Carroll’s comments on Wicca’s reaction to Chaos Magick’s critique of its historical roots touch upon the broader issue of religious legitimacy. The tension between historical authenticity and syncretic innovation is a recurring theme in studying new religious movements and esoteric traditions (Strmiska, 2005). Carroll’s observation that some Wiccans have embraced the freedom to evolve their practices reflects the ongoing debates within Wicca and other esoteric traditions about the balance between tradition and innovation.

Lastly, the fluidity of historic practices Carroll notes that many practitioners transition from one esoteric tradition to another, from Thelema to Chaos Magick, underscores the fluid nature of esoteric identities. This fluidity is a subject of academic interest, as it challenges the notion of fixed religious identities and highlights the individualised nature of contemporary spirituality (Heelas, 1996).

Carroll’s insights provide a valuable case study for understanding the complexities of religious and esoteric identities in the contemporary landscape. His comments reveal the tensions between orthodoxy and heterodoxy, historical legitimacy and syncretic innovation, and the fluidity of esoteric practices, all of which are topics of ongoing academic inquiry.

It’s also interesting to analyse the dynamics between orthodoxy and heterodoxy, the problems of legitimacy, and the problems of structures and hierarchies found in esoteric traditions. I wouldn’t say as much as in mainstream religions because I think in mainstream religions, that is much much more prevalent, and it is also institutionalised, whereas in esoteric practices, that tends to be more dependent on the group, the tradition, the individual, and you often find esoteric practitioners that rebel against hierarchies because there are a decent number of esoteric practitioners that decided to leave mainstream religions because they didn’t want to abide by any authority or to abide by specific hierarchies.

Now, on to the next question, which is on Chaos Magick and cultural traditions. My question was,

How do you reconcile Chaos Magick’s eclectic ethos with the cultural specificity of magical systems like Hoodoo or Cunning Craft?

Peter replied, Well, Hoodoo and Voodoo may have a certain cultural specificity to West Africa and to the African diaspora in the Americas, but it obviously has its roots in a syncretism between animist and ‘pagan’ beliefs in West Africa and the Roman Catholic beliefs of the Southern European colonial conquerors and slave owners. The extent to which Catholic clerics dabbled in occult practices on the side usually goes underestimated; after all, they wrote and used most of the grimoires.

‘Cunning Craft’ usually refers to the ‘folk magic’ of specialists amongst the common people of Europe (particularly Britain) in the late middle ages and early modern period. So far as we can tell, this seems to have consisted of a rich mish mash of instinctive animism, simple sympathetic magic, perhaps a few survivals of pre-Christian ideas, an occasional helping of learned ideas from grimoires that contained bits of biblical and classical scholarship, and often a bit of protective or sincere Christian gloss on the top. It does not seem to have manifested as a system with a widespread corpus of consistent ideas and practices.

Now, on to my commentary. So Peter J. Carroll’s reflections on the relationship between Chaos Magick and culturally specific magical systems like Hoodoo and Cunning Craft offer an intriguing entry point into the academic discourse on syncretism, cultural appropriation, and the fluid boundaries of magical traditions. By the way, I have a video on cultural appropriation and a round table with other Scholars and professors on cultural appropriation if the topic interests you. So, let’s go into the syncretism and cultural specificities.

Carroll’s acknowledgement of the syncretic roots of Hoodoo and Voodoo aligns with academic perspectives that view religious and magical systems as inherently hybrid and evolving (Chireau, 2003; Fanger, 2012). His comments suggest that Chaos Magick’s eclectic ethos is not necessarily at odds with the cultural specificity of these traditions, as they are products of syncretism.

Then, we have the matter of cultural appropriation and ethical considerations. While Carroll does not explicitly address the issue, his comments raise the question of cultural appropriation. The eclectic ethos of Chaos Magick could potentially lead to the appropriation of culturally specific practices, a topic of ethical concern within both academic and practitioner communities (Zimmerman, 2019).

Again, I would advise you to watch both my episode on Cultural Appropriation and Roundtable with other Scholars because it’s not a matter to fight over. It’s something that is very, very complex. And then we have the Cunning Craft and folk magic. Carroll’s description of Cunning Craft as a “mish-mash” of various influences resonates with scholarly accounts that portray European folk magic as a fluid and heterogeneous set of practices (Davies, 2009). This supports the idea that magical systems often lack a “widespread corpus of consistent ideas and practices,” challenging the notion of fixed, bounded traditions.

Carroll’s insights contribute to the ongoing academic dialogue about the complexities of syncretism, cultural specificity, and the ethics of appropriation in contemporary magical practices.

Now, on to the next question on the legacy of occult bookshops. My question was,

Could you reflect on the significance of places like The Sorcerer’s Apprentice in fostering the occult community and disseminating ‘Rejected Knowledge’ in the UK, especially during the pre-Internet era?

And Peter replied,

The Sorcerer’s Apprentice in Leeds went through a period in which it supplied a lot of paraphernalia like robes and wands and chalices along with books and its own in-house magazine by mail order. It also published the first editions of my books and that of some other authors. It also opened its shop and previous smaller premises as a tearoom on Saturdays as a meeting place for local occultists of all shades. It took a rather provocative stance for publicity purposes, and eventually Christian fundamentalists firebombed it, and it went mail order only with a much reduced public profile. Its proprietor tried to service all ends of the market and sold both trash and quality items with equal enthusiasm and hype, and this began to diminish its reputation amongst serious occultists.

Atlantis Bookshop and Watkin’s Bookshop both in London, have consistently maintained a high reputation for the supply of quality books and information on esoteric topics over many decades, and in recent years Treadwells Bookshop, also in London, has functioned in a similar way. Specialist occult/esoteric shops have largely disappeared from the provinces these days, except in esoteric hotspots like Glastonbury.

Now, onto my commentary. Peter J. Carroll’s reflections on the role of occult bookshops in the UK, particularly The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, Atlantis Bookshop, Watkin’s Bookshop, and Treadwell’s Bookshop, offer a valuable lens through which to examine the material culture of occultism and its dissemination in the pre-Internet era. This commentary aims to situate Carroll’s observations within broader academic discussions on the role of materiality, space, and community in the occult milieu.

So, the first aspect is the material culture and rejected knowledge. Carroll’s mention of the Sorcerer’s Apprentice’s wide range of offerings, from robes and wands to books, underscores the importance of material culture in occult practices. This aligns with academic studies that highlight the role of material objects in the construction and dissemination of ‘rejected knowledge’ (Hess, 2007; Pasi, 2014), like the study by Hess and one by Pasi.

Then, you have the community building and public spaces. The Sorcerer’s Apprentice’s function as a meeting place for “local occultists of all shades” speaks to the role of physical spaces in community building. This resonates with scholarly work on the importance of ‘sacred spaces’ in fostering a sense of community and shared identity among practitioners of alternative spiritualities (Chidester & Linenthal, 1995; Hill, 2017).

Then we have the impact of the controversial firebombing of The Sorcerer’s Apprentice by Christian fundamentalists, and its subsequent shift to mail order highlights the contentious nature of occult practices and the risks involved in public engagement. This incident can be contextualised within broader discussions on the stigmatisation and marginalisation of occultism (Introvigne, 2016).

And suppose you want to have an example of fundamentalists attacking people who deal with magic and esotericism. In that case, you can check out my short on whether witchcraft is forbidden in the Bible. You’re going to have some fun reading the comments.

Then, we have the final point in my commentary. Here, the changing landscape Carroll’s observation that specialist occult/esoteric shops have disappeared mainly from the provinces, except in “esoteric hotspots like Glastonbury,” points to shifts in the landscape of occultism, potentially influenced by the rise of digital platforms.

So it’s interesting because, as we said, the digital platforms and social media presence may make certain shops and certain bookshops disappear. Luckily, there are still a few.

Then, on to the next topic and question. So here, I will read three questions and three answers, and then I will give my commentary on all three of them.

So, the first question is on magic and empirical science. My question was,

You’ve often sought to root magick in scientific principles. Do you believe that empirical science could ever validate the existence or efficacy of magick?

And Peter responded,

Psychologists can readily validate the efficacy of belief and positive thinking. Physicists can usually manage to invalidate parapsychology to their own satisfaction, and I hope that they continue to do so because otherwise, we could become prosecuted for it or forced to work from behind barbed wire.

So then the other question is on physics and metaphysics, and I asked,

You’ve connected Chaos Magick to concepts in physics. How do you see the relationship between these physical theories and metaphysical principles in your practice?

And Peter replied,

All physical theories have underlying metaphysical elements. For most classical physical theories, that means causality and realism. Relativity theory also adds locality (nothing can travel faster than light). Quantum theory, on the other hand, asserts that in many situations, one or more of these grand meta-physical principles do not apply – randomness, indeterminate states, and instantaneous effects seem to govern what happens. Thus, for the magician, physical theories offer interesting choices of metaphysical principles.

And then the third question, before I comment on all three of them, is on quantum uncertainty. I asked,

Some argue that quantum uncertainty leaves room for the effectiveness of magickal practices. What’s your stance on the incorporation of quantum mechanics into magickal theory?

And Peter responded,

Chaos magic, in theory, and practise, usually adopts the assumption that uncertainty actually means indeterminacy (many physicists use this assumption, too) and that magic can somehow nudge indeterminate states to manifest in desired states. Such an approach favours enchantment (trying to make things happen) over divination (trying to work out what will happen) because if the future becomes increasingly indeterminate with time, then enchantments cast forward in time can take advantage of the indeterminacies whereas it will become increasingly difficult to divine past the indeterminacies, so we have the maxim ‘Enchant Long and Divine Short’.

When I teach people magic, I always start with enchantment – make a wand and some sigils and try and make something useful to you happen. Don’t bother with divination till later, and even then, try and use it mainly as a lateral thinking tool, not in attempts to work out what will happen in the future.

This is very interesting. So, let’s look at my commentary here. So Peter J. Carroll’s reflections on the relationship between magick and empirical science, as well as the incorporation of physical theories into metaphysical principles, offer a fertile ground for… here I am sorry for the slide again.

So, it offers us a way of looking into the physical and metaphysical theories and how the two interact. So I thought it was interesting his comment on the magic and the empirical science when he asserted that psychologists can validate the efficacy of belief. Positive thinking aligns with existing research on the placebo effect and the power of suggestion (Walach, 2011). However, his cautionary note about the potential for magicians to be “prosecuted” or “forced to work from behind barbed wire” if physicists validated parapsychology is a provocative claim that invites further exploration into the social and ethical implications of such validation (Hess, 2007).

Then we have – if you can see on the slide, metaphysics, physics and Chaos magic. Carroll’s discussion of the metaphysical underpinnings of physical theories like relativity and quantum mechanics resonates with academic work on the philosophy of science (Ladyman, Ross, et al., 2007). His assertion that physical theories offer “interesting choices of metaphysical principles” for magicians suggests a dynamic interplay between scientific theories and occult practices, a subject that merits further scholarly attention (Hanegraaff, 2012).

Then, we have the quantum uncertainty and magical practices. Carroll’s stance on quantum uncertainty as a basis for the effectiveness of magickal practices is particularly intriguing. His emphasis on “enchantment” over “divination” due to the indeterminate nature of the future aligns with broader discussions on the role of uncertainty in both scientific and occult contexts (Kripal, 2010). His pedagogical approach, focusing on “enchantment” as a starting point for teaching magick, could be seen as a pragmatic application of these theoretical considerations.

So Carroll’s Reflections contribute to the dialogue on these things, and I have to say that I agree with him on the matter that I personally do, even though I’m always open to being refuted by evidence. I think that it’s very difficult to have magic proven scientifically, whatever that means. But one thing that I think is that it is not even desirable. But, as I said, I could change my mind about that, but at the moment, that’s what I think.

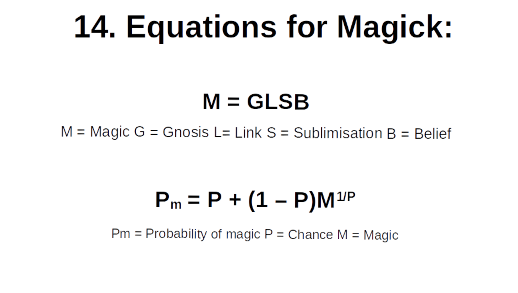

So, let’s move on to the next question. So, I will put this slide on so that you can follow along better with the equation of magic. But I’m still talking about what Peter J Carroll said. So, first of all, the question is on the equations for magic. My question was,

Could you elaborate on your “Equations for Magick”? How do they function as a theoretical framework for understanding how magick works?

And Peter replied,

They provide an empirical recipe for what you need to put into an act of magic and a formula for what you will likely get out of it. They do not tell you how the magic works or how to precisely measure the ingredients. They do, however, indicate the difficulties involved.

Firstly, the ingredients, M = GLSB, where all factors can vary on a scale of 0 – 1. The amount of magic M that you can bring to bear on an event depends on the amount of gnosis G (excited or quiescent mental focus) that you can bring to bear, the quality of the magical link L involved, which can range from low for a photograph or name only to medium for a personal memory, to fairly high for physical proximity and detailed knowledge of the target phenomenon. S stands for subliminalisation, the extent to which the magician can activate the desire powerfully in the subconscious rather than the conscious mind, and B stands for belief, both conscious and subconscious, that you can create the required change. Obviously, if any of the GLSB factors fall much below a perfect 1, then they will reduce the resulting magic factor M.

The formula for the effect of the magic runs as follows: –

Pm = P + (1 – P)M1/P

Where Pm shows the probability of achieving the desired result by magic, P represents the probability of the event occurring by chance. (In the case of divination, P represents the chances of randomly guessing the right answer). The Magic factor enters the equation raised to the power of the reciprocal of the natural probability. This reflects the empirical datum that only an exceptional act of magic will make any significant difference to an event of very low or very high natural probability and that anything less than a perfect act of magic seems most usefully applied to events with a medium natural probability of occurrence.

For example, a personal lottery win has an exceptionally low probability of natural occurrence, and feasible forms of magic will make little difference, but a series of conjurations applied to a string of medium-probability business deals can nudge reality into providing the equivalent and more.

Then, I also asked a question on scientific receptivity to Magic. I asked,

How receptive do you find the scientific community to the intersections between science and magick? Are there any scientists or theories you feel are particularly aligned with your views?

And Peter Carroll says,

Dr Rupert Sheldrake has created some ‘magic friendly’ parapsychology experiments that have given believers in parapsychology great satisfaction, but some science-minded sceptics have questioned his experimental procedures and his seemingly very positive results. His telephone telepathy results look very impressive to me.

Dr Dean Radin has created some rather ‘magic unfriendly’ parapsychology experiments designed to convince even the hardest scientific sceptics. The results seem above chance expectations but not far enough beyond them to remove all reasonable doubt. He has also created some rather more ‘magic-friendly’ ones that have given more positive results.

It seems that a trade-off exists between making the experiments magic-friendly by making them exciting, emotionally engaging, non-repetitive, and close up or hands-on for a better link and making them science-acceptable by insisting on calm laboratory settings, tiresomely repetitive tasks and reproducible results.

Emeritus Professor John Cramer apparently gets frequently asked about the metaphysical and occult/esoteric implications of his Transactional Interpretation of Quantum Physics, but he has a prestigious academic reputation to preserve…….

So now my commentary on both these questions. So, first of all, on the equation of magic, Carroll’s equations of magic. I think it’s very interesting, and it’s something I found in other authors as well. There’s, for instance, Jason Miller, who also talks about the fact that the effectiveness of magic and how you plan your magic and your ritual to be effective strongly depends on the likelihood of the event to occur even without magic, so this is something that Carroll mentions long before him.

So Carroll’s “Equations for Magick” serves as a heuristic model for understanding the variables contributing to magickal practices’ efficacy. The equation M = GLSB encapsulates the factors of gnosis (G), magical link (L), subliminalisation (S), and belief (B). This equation resonates with existing scholarly work on the role of intentionality, focus, and belief in ritualistic and magickal practices (Luhrmann, 1989; Kripal, 2010). His second formula, which calculates the probability of achieving a desired result through magick, adds a quantitative dimension to the often qualitative discussions in the study of magick and the occult (Hess, 2007).

Carroll’s mention of Dr. Rupert Sheldrake and Dr. Dean Radin highlights parapsychology’s contested space within the scientific community. His observation that a “trade-off exists” between making experiments “magic friendly” and “science acceptable” echoes broader debates about the methodological challenges in studying phenomena that exist at the fringes of mainstream science (Walach, 2011). The mention of Emeritus Professor John Cramer’s Transactional Interpretation of Quantum Physics adds another layer to the discussion, suggesting that even theories within mainstream physics can have implications that resonate with esoteric and metaphysical concepts (Ladyman, Ross, et al., 2007).

Carroll’s reflections contribute to a nuanced understanding of the relationship between magick and empirical science. His “Equations for Magick” offers a framework that could be further explored and tested within academic settings. Moreover, his comments on the scientific community’s receptivity to magick underscore the complexities and challenges of integrating esoteric practices into empirical research.

So, yeah, this is pretty much the end of the interview, and now I can take your questions. Here I am. I hope it wasn’t too long, but I appreciate your staying here. You are fighting against the diminishing attention span and lack of depth that social media and the digital age create, so kudos to us. If Peter J. Carroll is watching this, thank you so much for answering my questions and doing this interview. If you are in the chat, I would love to hear your thoughts. Let me first take the questions, and then I can make some comments myself.

Thank you so much, Mark, and thank you for your Super Chat.

Then there’s a question here: ‘Good morning. Why are there eight points on the star of chaos?’

That’s a good question. You may have noticed that on my slides, there’s the eight-pointed star of chaos magic, which is why I chose it to represent Peter J. Carroll since we don’t have any images we can use. What does the star of chaos mean? The eight-pointed star, often called the chaos star, is a symbol commonly associated with chaos magic. Peter J. Carroll popularized the symbol. The eight points of the star are generally understood to represent the eight types of magic in Carroll’s system, as outlined in his foundational text, ‘Liber Chaos’ or ‘Liber KAOS’.

The eight types of magic that the star represents are:

- Octarine, pure magic: The magic of the pure self, often represented by the colour octarine, a fictional colour from Terry Pratchett’s Discworld series.

- The second one is Black, Death Magic, Concerned with the themes of death, endings, and closure.

- The third one is Blue, wealth magic, Focused on material wealth and well-being.

- The fourth one is Green, love magic, Concerned with all forms of love, attraction, and affection.

- The fifth one is Yellow, ego magic, Focused on the self, ego, and individuality.

- The sixth one is Purple, sex magic: Concerned with sexual energy and practices.

- The seventh one is Orange, thinking magic, Focused on intellect, knowledge, and communication.

- The eighth one, the Red one, is war magic, Concerned with conflict, power, and strength.

The eight points also serve as a visual representation of the concept of chaos, embodying potentiality and the inherent unpredictability of magic and existence. The symbol is meant to be disorienting, representing the complexity and fluidity of the magical and natural world.

I hope that this answers your question. I don’t see any more super chats.

So, let me see if there are any other questions. I think this was a great interview, and I thank you guys, especially those who contributed when I asked whether you had any questions for Peter J. Carroll. I tried to combine all these questions, at least to identify patterns, and see whether I could make everybody happy, which is probably impossible. But I hope that I did as well as I could.

I’m looking at the chat now. It seems that you guys have been quite lively. I’m sorry that I couldn’t pay attention to the chat; I had a lot of things going on here, and I wanted to provide you guys with a coherent interview and analysis. So, if you guys have any questions, you can Super Chat them now or repost them with ‘QUESTION’ in capital letters so that I can see them.

f you want to hear my final thoughts, I think there are some interesting elements in this interview that are probably also useful for practitioners. One element that I found very interesting is the idea of artificial intelligence. He’s also sceptical about whether technology and artificial intelligence can be effective in magic. But the part that I found most intriguing is the idea that artificial intelligence is like using or working with a demon or an entity from afar, and you don’t know where they’ve been. So, it’s like, why would you trust them? It’s better to use servitors that you have created yourself. It was quite an interesting perspective. I’d like to know whether there will be digital AI magicians who will create their own AI as servitors. This is because the AI we have at our disposal has been programmed and created by others, which is why Peter Carroll made that comment.

Another interesting aspect is the equations of magic. Those who don’t practice magic and are often detractors of it tend to think, ‘Oh, if you cannot move a mountain, then magic doesn’t exist. This is a comment that I always found very bizarre, lacking nuance and a critical understanding of what magic even is. It would be like saying, ‘Oh, you say you have a brain, but if you cannot solve all the equations in the world, then it’s not true. You don’t have a brain. You’re not intelligent unless you can read an entire library in a day.’ You know, this kind of extreme, ridiculous comments that I hear from people who are often not practitioners and very often strong materialists. They see magic as something very extreme that has nothing to do with how the world works.

But what would make people think that if the world and things in the world work by the likelihood of certain events happening, why would it not be the same with magic? There’s still that idea of the supernatural, which was very Victorian. After the Victorian era, the idea of magic being supernatural has declined, and now there’s more of the view that magic is very natural. So, I think those equations are very interesting because they highlight the nuances of magic and how magic works. Many people, especially non-practitioners, still need to understand that it depends on the likelihood of an event, how you should structure your ritual to make it effective, and even if it is possible to have an effective one. It’s not like either you can do the absolute impossible or magic doesn’t work or exist. I always find it bizarre that people apply this extremely polarized, black-and-white thinking to magic and not other things.

So, Craig Delany asks, ‘How much are emotions important to the work?’

I don’t want to answer in place of Peter J. Carroll because I don’t want to claim to know his answer. I could tell from his answers that he thought that the intention and the effort you put into the ritual were very important. I speculate that emotions also play a significant role from his point of view. That also is part of the equation of magic. As for me, I’ve seen among practitioners as an anthropologist of religion that emotions play a significant role for most practitioners. It is, in fact, a driving force for magic for many practitioners I have encountered. So, there’s a high degree of importance there.

Also, thank Andrew, João, and Edward for moderating the chat. And what else… I’m trying to see whether there are other questions; otherwise, I guess that we can end the live from here.

So, yeah, I can answer a final question. ‘What’s the importance of Castaneda’s work on chaos magic?’

For those of you who are not familiar, Carlos Castaneda is the author of books that have popularized transcultural shamanism or neo-shamanism. I prefer ‘transcultural shamanism’ because it’s more informative in the Western world. He talked more specifically about the Mexican form of shamanism, but then he became a popularizer of forms of transcultural shamanism in the Western World. Then you have core shamanism, probably the most popular form of transcultural shamanism. They have been influential. That’s not Peter Carroll’s answer; it’s my answer. If you read the books by Peter Carroll, you will find that there is a description of shamanism as something… I have a memory of this genealogy that draws me back. Chaos magic derives from different traditions, and if I remember correctly, the root one was shamanism. So, I think there’s a discourse about shamanism being the root of all religions. It’s a very 20th-century discourse. So, I think that it was likely an influence, but I would love to hear what Peter Carroll thinks about it.

There are other people, like other authors like Phil Hine, who emphasize the shamanic element a bit more in combination with chaos magic. Suppose you’re interested in the trade-off, knowing about the experiments mentioned. Do you think there can be a way to publicly show results convincing enough without a strict scientific trigger?

No. First of all, we live in a materialistic and very scientifically oriented time in our history, and in many ways, that’s a good thing. I’m an academic, so I’m not against science. I don’t particularly like scientism, which is different from science. That’s the belief that science can explain everything and anything. So, I have a problem with scientism, but I love science. I definitely love science and academic knowledge. It’s the way that we can gather information most accurately. Although it’s always important, and I always say this, accurate information is not the same as truth. Truth is something metaphysical, and accurate information is something that is verifiable and useful on a day-to-day basis. And accurate information changes over time.

So, I’m not a fond believer of the idea of objectivity. I don’t think that things remain static, to be honest. So, I think that with magic, in my view, magic works in ways that just elude the scientific method. That’s why I don’t think that it could be proven. And I don’t think that magic practitioners need for it to be proven, to be honest. Because I see magic more in the realm of religious and spiritual beliefs rather than in the realm of academia. I think these two things are different. Academic knowledge and science are one thing, and magic, practice, religion, and spirituality are another thing. One could be useful to inform the other, but I think pursuing truth in science and academic knowledge is problematic. Because I don’t think science and academic scholarship are after the truth. As I said, that’s a metaphysical concept. It’s not what science is about.

Science is about usefulness and finding accurate knowledge so that you can navigate the world, the material world, I should add, in the best way possible, in the most useful way possible. So, my impression is, but as I said, I’m very willing to change my mind if evidence proves otherwise. My impression, based on fieldwork and what practitioners have told me over the years, is that magic works in a very different way. It’s like trying to weigh your soul with a scale. And if you cannot weigh your soul with a scale, then it doesn’t exist. That’s not a question that science is meant to answer, in my view. I know that there are some branches of science that try to answer these types of questions, and I find those problematic, to be honest. But I’m always in favour of any type of study, to be frank, because I could very well be wrong. And, you know, the more evidence we have and the more studies we have, the better.

So, I think that we can end our livestream here. Thank you all so much for coming over. Thank you to those who sent super chats, and thank you to Peter J. Carroll for this interview.

So, I think that we can end our livestream here. Thank you all so much for coming over. Thank you to those who sent super chats, and thank you to Peter J. Carroll for this interview.

Remember to sign up for my newsletter and leave me a comment below. If there is any question that you have, or any comment, or any observations based on this interview, I’d love to know. Share this video or any of my videos around because that really helps the Symposium grow. And if you have the means to support this project financially, you’ll find all the ways in the description. I thank you for anything that you can do for the Symposium. This is a symposium, after all, right?

So, thank you all so much, and stay tuned for all the academic fun.

Bye for now!

Peter J. Carroll is a key figure in the development of Chaos Magick, and he has authored several books that have become foundational texts in the field.

Here is a list of some of his notable works:

1. “Liber Null & Psychonaut” (1987) – https://amzn.to/3LYrvb9

2. “Liber Kaos” (1992) – https://amzn.to/3PVXyK2

3. “PsyberMagick: Advanced Ideas in Chaos Magick” (1995) – https://amzn.to/3S0QBKe

4. “The Apophenion: A Chaos Magick Paradigm” (2008) – https://amzn.to/3QiJR9g

5. “The Octavo: A Sorcerer-Scientist’s Grimoire” (2010) – https://amzn.to/45xpwRV

6. “EPOCH: The Esotericon & Portals of Chaos” (2014) – https://amzn.to/3S5ZouB

Peter J. Carroll’s official website is Specularium (https://www.specularium.org/), where you can find more information about his works, theories, and other contributions to the field of Chaos Magick and esoteric studies.

REFERENCES

Asprem, Egil. “The Problem of Disenchantment: Scientific Naturalism and Esoteric Discourse, 1900-1939.” Brill, 2014.

Hanegraaff, Wouter J. “Esotericism and the Academy: Rejected Knowledge in Western Culture.” Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Hess, David J. “Science Studies and Activism: Possibilities and Problems for Reconstructivist Agendas.” Social Studies of Science, 2007.

Kripal, Jeffrey J. “Authors of the Impossible: The Paranormal and the Sacred.” University of Chicago Press, 2010.

Ladyman, James; Ross, Don; et al. “Every Thing Must Go: Metaphysics Naturalized.” Oxford University Press, 2007.

Luhrmann, Tanya M. “Persuasions of the Witch’s Craft: Ritual Magic in Contemporary England.” Harvard University Press, 1989.

Owen, Alex. “The Place of Enchantment: British Occultism and the Culture of the Modern.” University of Chicago Press, 2004.

Pasi, Marco. “Aleister Crowley and the Temptation of Politics.” Routledge, 2014.

Partridge, Christopher. “The Re-Enchantment of the West: Alternative Spiritualities, Sacralization, Popular Culture, and Occulture.” T&T Clark International, 2005.

Pasi, Marco. “Aleister Crowley and the Temptation of Politics.” Routledge, 2014.

Walach, Harald. “Placebo Studies and Ritual Theory: A Comparative Analysis of Navajo, Acupuncture and Biomedical Healing.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 2011.