[We apologise that some images have been removed from this page due to unclear copyright labelling]

Dr Angela Puca: Hello everyone! I’m Dr. Angela Puca and welcome to the live stream Symposium. As you know, I’m a PhD, a university lecturer, and a religious study scholar. This is your online resource for the academic study of magic, esotericism, Paganism, Shamanism, and all things occult.

Before we start, I’d like to remind you that this project is brought to you by you. This might be a better view. So, this project is brought to you by you. I would encourage you, if you have the means, to support this project of delivering free academic knowledge based on peer-reviewed research by supporting my work. You can do this by joining my Patreon, my Ko-Fi, sending one-off donations, sending super thanks, super chats, or joining memberships. Also, please sign up for my Newsletter. You will find the link in the description box, which will also be in a pinned comment.

Because we cannot rely on the capricious algorithms, which change every so often, and social media platforms that can shut down whenever they decide, if you sign up for my newsletter, you will always be up to date with whatever I’m doing. It is our own community, so I would encourage everybody to do that. So, yeah, and otherwise, of course, you can also support this work by sharing my videos around, leaving me nice little likes, which I normally say, “smash the like button”, and any type of support that you can give to this project is massively appreciated.

Dr Angela Puca: So, I have bad news for you guys and for me, in fact. I don’t know why I have the headphones on. We got stood up. I don’t know what happened, but our guest didn’t show up. I hope that she’s okay and nothing serious has happened, of course, but I’m afraid that you’re left with me. I think that I don’t really want to do live interviews anymore because it is too stressful. So, yeah, I’m even considering not doing live interviews anymore, to be honest, because this is the second time that it’s happened, and I find it very stressful.

Anyway, change of topic all of a sudden. I think this is going to be a Q&A, after all. So, if you have any questions about the academic study of esotericism, magic, paganism, shamanism, and all things occult, I would suggest that you put “QUESTION” in capital letters in the chat so that I can answer your questions. I’m sorry that you were expecting a chat on Kenneth Anger. I was expecting that, too, but alas, you’re stuck with me. So, thank you also to Andrew and João, who are moderating the chat. It’s always very nice to have the help of my lovely Patrons and moderators. We always have a lot of fun on Discord. Yesterday, we had a Magus Lecture on esoteric entities, entities that are found in esoteric practices, esoteric traditions, and magic workings, discussing the different types and so on. So, we had a lot of academic fun.

So, let’s see if there are any questions. I haven’t done a Q&A in quite some time. Apparently, now it’s the thing that I do when I get stood up. So, let me see if there are questions. Oh, thank you, Edward, as well, for moderating the chat. Let’s see if there are…

Oh, Karl says, “The new newsletter is great, well worth signing up for.”

Oh, that’s really sweet; thank you so much. One thing that I like about the newsletter is that I don’t have to censor myself, for lack of a better term. You probably know that depending on social media, there are different policies on what you can say and what you cannot say. So, I have to work around that when it comes to making videos or making content for social media. Whereas on my newsletter, I can literally write whatever I want. So, I also like that. I also try to include pictures and links to interesting things that I think you might like. Thank you, Karl, I’m glad that you’re liking it. Let’s see if there are more questions.

Dr Angela Puca: Oh, Karl is also asking, “How did the Harvard talk go?”

It was great. I don’t know how many of you guys attended that. Let me know in the chat box if you attended it and what you thought about it. I think it was great. I was surprised by the format. It was more of an interview-style session, but it was really great. It was primarily about my backstory and how I came up with the idea of starting a YouTube channel. As you know, I’m on various social media platforms, and I also have a podcast now, but the talk was primarily focused on the YouTube channel. I think that’s where most people discover my work anyway. We discussed how I got the idea for the YouTube channel, how things developed, and the importance of academic outreach.

One of the core things that we talked about at Harvard was the importance of academic outreach. Academic scholarship is difficult to find, access, and even understand, to be frank. I think we, as academics, could do a better job at making it easier to understand. I mean, how can we blame practitioners and the general public for not knowing things when they are made to be so obscure and difficult to find? You kind of have to have a certain training as a researcher to know where to find papers, how to read them, and how to interpret them. This is something that you really need to be trained on. That’s why there are so many myths, even in terms of health, fitness, and religion.

During the time of the lockdown and everything that happened, I think it became evident how the general public didn’t have the training to understand and interpret papers in context. Every single study was interpreted as the truth, and when they contradicted themselves, it seemed like, “Oh, science doesn’t even know what’s going on,” which is not how science works. I think people tend to believe that science is meant to deliver the truth, but it’s not. Science and academia are about finding the most accurate knowledge that you can. This knowledge can vary depending on the type of methodology used, the laboratory where the scientific experiment occurs, and many other factors. These factors are all very important because you then put all that data together to discern the most accurate knowledge and evidence from the massive data you have. So, never rely on just one study, especially when we talk about natural science.

It’s a bit different in the humanities and social sciences, but it’s a good rule. In religious studies, for instance, you don’t have as many studies where you can do a systematic review on one specific topic. You’re lucky if you have one paper on certain topics. But in natural science, where you do have many, many studies, it’s essential to put them in context. It’s not just about one study; it’s about the network, the body of knowledge that is produced with regard to that specific topic. So that’s something that’s important to stress. The talk at Harvard was great, and I really like Professor Joanna Parmigani, who works there. We’ve collaborated in the past, and I look forward to future collaborations.

Oh, Dave is asking about the tutoring I offer on my website. Does it differ from or complement my YouTube work?

Yes, for those who have checked my website, you’ll find a section called “services.” You can commission a YouTube video or get a tutoring session. It varies from what I offer on YouTube because it’s tailored towards the person asking for the session or lecture. You choose the topic, and we schedule a session together. If you’re interested, you can check it out on my website, drangelapuca.com.

Let me see if there are other questions.

Peter says, “The knowledge of esotericism seems to be very dispersed, and it’s not easy for a non-practitioner to get an easy overview of the field. Are there any classics, or is there any kind of school?”

I guess you’re talking about studying esotericism as a practitioner and not as an academic. It’s a good question. There isn’t a general source, but there are dictionaries of esotericism. One famous one, which might be hard to find, was edited by Woulter Hanegraaff, which I’ve often referenced in my videos. It could be interesting because it provides different key terms and traditions, along with historical background. However, it’s more academic, not from a practitioner’s point of view. As a practitioner, I’d advise trying to learn about many different traditions. Probably starting with understanding a bit of Theosophy and the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn would be helpful, even from a historical perspective, because it allows you to better understand the two main pillars upon which other esoteric traditions, especially in the Western world, are based and have been massively influenced from.

So, I would recommend just watching my videos. I have quite a few videos on different traditions. Watch them, see which one intrigues you, and look in the info box. You will find some sources that you can look up. But yeah, I agree; I don’t think it’s easy, and I don’t think it’s meant to be easy because it’s your own path. You just have to explore what resonates with you and follow the signs, as practitioners usually say. So, I hope that helps.

Let me see if there are other questions. Andrew is talking about the MA at Exeter in contemporary magic. We’ll see; I might reach out to them. It would be interesting to collaborate; I’m definitely open to that. Let me see if there are other questions. I can see a question by Dejan on Aleister Crowley and Kenneth Anger, but unfortunately, I don’t have the expertise to answer that, I’m afraid.

That’s a good question and always one that requires a lot of explanation. At the moment, I’ve recently delivered the final version of my book for Brill, which will be called “Italian Witchcraft and Shamanism”. And thank you, Andrew, because he’s my research assistant and helped me with the proofreading. The final version has been sent out, and I’ve been told that, hopefully, in the next six months, fingers crossed, it should be out. I really hope that it does. And of course, I don’t know how much it’s going to cost, but it’s going to be high. So, I would recommend getting it at a library because, unfortunately, authors don’t get to decide those kinds of things, and academic publications tend to be quite pricey. In fact, I had a conversation at the University of Cambridge when I was there for a conference. There was a publisher—probably it’s better to leave it anonymous—but I had a long conversation with this academic publisher asking why academic books are so incredibly expensive. Especially considering the fact that commercial publications give authors royalties, while with academic publications, sometimes you don’t get any royalties. Other times, you get very, very little royalties compared to commercial publications, which cost much less. But the answer was that they don’t sell as much. Also, they are meant for libraries, academic libraries, or colleges and universities. They’re not really meant for the general public.

I think it’s a bit of a shame. In some cases, if you’re an author and you want to publish open source, you have to pay a lot—like a lot—to make it available Open Access. So it’s a bit frustrating. I was also asking why they don’t have things like audiobooks for academic books. Because I find audiobooks very helpful. I like them a lot, to be honest. It makes reading easier, especially when you have to do other things like cooking and other mundane tasks. But they said that there isn’t a market for that. So maybe in the future, academic publications will become a bit more popular, and this will happen.

So, in terms of my research—sorry, I got sidetracked, Andrew—but in terms of my current research, I’m working on a paper for the American Academy of Religion. It’s going to be on the concept of open and closed practices. I talked about that in a recent video when I was in Italy about whether Italian witchcraft is an open or closed practice. But this paper is meant to be more generally about the concept of open and closed practices, which is a concept that has recently emerged in the public discourse among the communities of practitioners. So, it’s interesting to investigate because, as far as I know, there isn’t really any academic research yet on the topic.

There is a new feature on YouTube, and I don’t even know how it works, but thanks. I wonder whether you gifted it to somebody random or to a specific person. I really don’t know how it works.

So, Dave is asking, in the Inner Symposium, which is the Patron Community, we discussed different entities yesterday. Do you think an AI can be a Servator or a Tupla?

Even perhaps people should be aware of what we discuss. Well, that’s Patreon for that. And also, for the Magus and higher tiers, you also have access to a database of all past lectures, including this one. So, yesterday, among the different entities, we also discussed the entities that are created by practitioners. The two main ones—well, we also talked about the egregor, which is a thought form that is created by a community around a symbol, subject, or topic. But then you have the servitor, which is an entity created by the practitioner for a specific purpose. Sometimes, it just dies out after the purpose has been fulfilled. In other cases, it is something more regular. A Tulpa, which comes from Tibetan Buddhism, is also created by the practitioner, but it is believed to take on its own life. So it becomes, you know, almost an independent entity that can have its own ideas, ethics, wants, needs, and things they don’t like. It is a bit more complex and complicated compared to a servitor.

So, yesterday, we were talking with the Magus Patrons: what if AI can be a Tulpa? Because there’s the idea that, at the moment, it is doing what people are programming it to do. But can it develop its own way of thinking? I guess this concept in tech is called “emergence.” And whether it can develop consciousness or self-direction. In that case, I suppose it would be a Tulpa. So, if AI develops emergence and emergent qualities, then it could be a Tulpa. How fun would that be?

Let me see if there are other questions. So, Peter asks, “What kind of people do you find in your field of study?”

Or is there any kind of pattern that you have observed in the type of people you encounter in the scientific community and related to that? Your question is a bit confusing to me. At first, I thought you were referring to practitioners because I do fieldwork—I’m an anthropologist, so I do fieldwork with people. Initially, I believed you were referencing my informants and the practitioners I worked with during fieldwork. But reading the second part of the question, I guess you’re asking about the academics in my circle.

So, what type of people are there in academia in these circles? Well, honestly, I think my view is primarily European. It’s possible that in other areas of the world, this could differ. I’ve also worked and collaborated with scholars from Australia and other countries. I’m trying to think about the countries: mainly Europe, but I also have colleagues from the US with whom I’ve worked quite a bit and Australia. I can’t recall anyone from New Zealand at the moment. Bearing that in mind and recognizing it might be a bit Eurocentric, I genuinely appreciate my field and my colleagues.

My impression, which is very personal, is that we’re all somewhat like the “outsiders” who venture into academia to study something very obscure. It’s challenging to study academically because few want to fund such research. I genuinely like my colleagues. My impression is that there isn’t much competition or attempts to tear each other down. But as I said, this could just be based on my experiences. My experience has been very positive, to be honest. The scholars I know are generally kind. They genuinely care about the field. Perhaps it’s because the field is so small, and we always feel under threat.

And I know, unfortunately, of quite a few colleagues who feel constantly stressed because the department might take away their funding, and they might not have a job anymore because of what they study. So, I feel that, probably because it is a small field, we are all extremely passionate about what we do. Otherwise, we wouldn’t have chosen this kind of job because you can be sure that it’s not easy. We tend to stick together. That’s my impression. There’s a collegial atmosphere. I’ve heard from people in other fields, even within the humanities, not specifically religious studies or the study of esotericism or paganism, which are the ones I’m referring to, that report something very different. Even those who research philosophy or history report much more brutal treatment by other colleagues.

In my field, the reason for that type of competitive and negative interaction between scholars doesn’t seem to exist. I hope it always stays like that because I’m not a competitive person. I always think that collaboration is always better than competition. In the long run, if you’re competitive, it may feel like you win at the moment when you feel, “Oh, I’ve done better,” but then, in the long run, what have you got if you don’t have a community? If you don’t have colleagues who are friends? For me, it’s not just about achieving something; it’s also about what’s around you when you’ve achieved that thing. If there’s a desert around you when you’ve achieved one thing, I don’t know; it feels like even that achievement loses its shine. You can’t even enjoy it. The only person I’m competitive with is myself. I try to do better every time, but I genuinely try to avoid competition with other people as much as I can. I hope that answers your question.

Let me see if there are other questions.

Knight Gaunt says, “Along the idea of an AI being used as an egregor, here’s food for thought: what about creating a basic AI chatbot and offering it as a digital vessel to a spirit entity as a means to talk?”

That’s interesting. I don’t know. What do you, practitioners in the chat, think about that? That’s an intriguing point.

Let me see if there are other questions.

Is there an umbrella organization facilitating the creation, communication, and distribution of the academic investigation of esoterica?

An umbrella organization? There are associations, if that’s what you mean. There are some academic associations. There’s the ESSWE, the European Society for the Study of Western Esotericism. There’s another one, which is European. Sorry, those are the two that I’m familiar with. And then, as you guys know, I’m at the moment working with RENSEP, the Research Network for the study of Esoteric Practices. My patrons have free access to their platform. RENSEP is also trying to bridge the gap between academia and the community of practitioners. They are also funding research and trying to make academia a bit more accessible. But other than RENSEP, I’m trying to think. Oh, also there is Trans States, which is a conference that happens in the UK and is addressed to both practitioners and academics. But I see that more as bridging the gap. It’s difficult to answer that because one organisation that facilitates, communicates, and distributes? That’s a lot. But over time, one of these associations, or maybe new ones, will emerge that will do that. Definitely, RENSEP is one that you might want to look up.

So, this is the most asked question on my channel: Do you practice any occult tradition yourself, or is it just an academic interest?

What do you guys think? Can we have a poll in the chat? I’m curious to see what you think. If I’m a practitioner or what? But the answer, for now, is that I’m not revealing that publicly whether I am a practitioner or not. Maybe in the future. I haven’t decided yet, but the thing is that being an academic in esotericism is difficult enough, even if you don’t talk about whether you are also a practitioner or not. So, for now, as I was advised by a mentor, I better keep quiet. And then, in the future, who knows? I’m hoping that at some point, I will be able to tell you guys. But I’m curious to know what you think. Tell me in the chat. I’m trying to look at the chat and see. Oh, this is João. He works in IT, is that correct? Or in technology? You can definitely define and develop personalities to talk using LLM textgen apps.

Oh, our guest has arrived. So, hello, Judith.

Prof Judith Noble: Hi.

Dr Angela Puca: Let me get this on.

Prof Judith Noble: I’m so sorry.

Dr Angela Puca: Is everything okay?

Prof Judith Noble: Yes, I’m so sorry. I’ve had no internet for the last four hours.

Dr Angela Puca: Oh, wow.

Prof Judith Noble: I’ve only just been able to go online. So, I’m looking slightly panicked and dishevelled, but everything is okay. And I apologize profusely to you and to everyone for being so late. But I’m here now if it’s not too late to do something.

Dr Angela Puca: Yes, absolutely.

Dr. Angela Puca: I think that we can start talking about our topic then. First of all, let me introduce you. Judith Noble is Professor of Film and the Occult at Arts University Plymouth. She began her career as an artist filmmaker, exhibiting work internationally, and worked for over 20 years as a production executive in the film industry, working with directors including Peter Greenway and Amma Azante. Her current research centres on artist’s moving image, surrealism, the occult, and work by women artists. She has published on filmmakers including Maya Deren, Derek Jarman, and Kenneth Anger. Her most recent publication, as editor, is “The Dance of Moon and Sun: British Women and Surrealism“. She continues to practice as an artist and filmmaker, and her most recent film is “Fire Spells“, a collaboration with director Tom Chick. Her recent work can be found at www.iseu.space, and her film work is distributed by Cinenova. You can also find all this information in the description box. So nice to see you, Judith.

Prof. Judith Noble: Gosh, sorry. I’m a little less prepared, visually, than I was hoping to be. I hope this light is…

Dr. Angela Puca: No, it was better. Yeah, just leave it.

Prof. Judith Noble: Okay, yeah, it’s okay.

Dr. Angela Puca: So, everybody is welcoming you. I think, shall we crack on and start talking about Kenneth Anger?

Prof. Judith Noble: Yes.

Dr Angela Puca: Could you tell us who he was, his work, and why it was innovative?

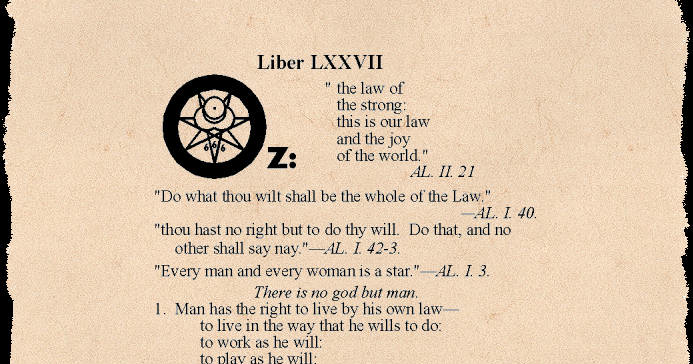

Prof Judith Noble: Okay, so Kenneth Anger was one of the great American avant-garde filmmakers. I’m saying “was” because, sadly, he died earlier this year at the age of 97. He began working on the west coast. He was born and brought up in Hollywood and started as an independent filmmaker in his teens. He made his first film, “Fire Works,” in 1949. At the same time, he was becoming very involved in the occult world of magic, working predominantly in the Thelemite tradition. Hence, his films reflect that. Oh, someone’s ringing my doorbell. I’ll just ignore it. It’s not a very good day today; I’m so sorry. From the beginning, his films were magical acts. They were made as magical acts, and watching them can also be a magical act if you wish. After “Fireworks“, he went to Europe at the invitation of Jean Cocteau and travelled around for four or five years. He made a film called “Rabbit’s Moon” in Paris in 1953 and another in Italy titled “Eaux d’Artifice.” He then returned to America and, in 1954, made “Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome,” which I suppose is one of his most overtly occult films. It’s a film I’ve been doing a lot of work about. In the 1960s, he became a significant figure in the counterculture on the west coast, bridging radical queer politics with the occult. More films followed: “Scorpio Rising” in 1963, “Invocation of My Demon Brother” in 1969, and “Lucifer Rising” in 1981.

So, there’s a brief historical overview. One thing to note about the films, in addition to their magical content, is that they are extremely beautiful to watch and technically complex. Anger worked on analogue film, on celluloid, before the digital era. Special effects had to be handmade, and his films have hand-printed overlays with many images. His technical mastery of the film medium is extraordinary. He was deeply respected by artists, filmmakers, and the avant-garde and independent film community, not only for the films but also for their incredible technical beauty and brilliance. So, that’s a very brief overview. I hope this gives us something to talk about.

Dr Angela Puca: Yes. What makes Kenneth Anger different?

Prof Judith Noble: What makes Kenneth Anger different? Well, there is absolutely no one like him in the history of filmmaking. He is truly unique. I suppose, for Kenneth Anger, when he would write his magical biography, the way that occultists do, he would describe the film, or the “cinematograph” as he liked to call it in his early days, as his magical weapon. What you have to bear in mind is that for Anger, the films themselves are the magic. They’re not films ‘of’ magic, they’re not recordings of something that takes place elsewhere, and they’re not documentaries. The films themselves ‘are’ the magic. I believe he was the first filmmaker to truly grasp and implement that, and that was something absolutely unique. While others may have followed in that tradition, they haven’t done so in quite the same way. So, I think that’s the truly extraordinary aspect of Anger’s work.

For instance, if we talked about Aleister Crowley, who profoundly influenced Kenneth Anger, magic for Crowley might be a ritualistic piece of sex magic or some other kind of manifestation. For Anger, it isn’t. It’s the film itself. That’s why, if you’re a practising occultist or magician, watching Anger’s work is such a fascinating experience. Watching that film is the magical act itself.

It’s challenging to break Kenneth Anger down into component parts because you get one glorious whole. Other characteristics of his work include his queer identity. The films all reflect a queer sensibility and sexuality. They don’t do that in a blatantly obvious manner; it’s just a part of the film, and you accept it as such. Additionally, his profound love for cinema is evident. He had immense reverence for silent cinema. Members of his family had worked in Hollywood before the Second World War, so he not only used the language of silent cinema but also its props and aesthetics. That becomes a part of the mix as well. From the mid-50s onwards, he adored popular culture. Working on 16 mm film, he couldn’t use sync sound — recording sound straight onto the film wasn’t technically possible. So, he pioneered the technique of using pop music and editing the film to match the music’s rhythm. He inadvertently birthed the soundtrack technique that later became foundational for the music video industry and, until about the end of the 1970s, the porn industry as well.

So, he was a technical innovator. However, for him, this was merely about making it work the way he wanted. All these facets make him unique. But, as I say, I don’t believe they can be dissected. You can’t say one part of him is a magician, another part is a queer man, or another enjoys editing films to early 60s girl group music. These elements can’t be separated; they come together as one beautiful, unified package. That’s what makes him such a significant filmmaker. And I haven’t even touched upon his use of colour. All his films utilize colour, and he employs it in a magical sense. He adheres to the Golden Dawn and Crowley colour scales, so colour holds a magical significance in his films and is very rich and immersive. There’s all of that at play if that makes sense.

Dr Angela Puca: And you mentioned that, for Kenneth Anger, the movie is the magic itself. Could you elaborate on that? In what ways were his movies akin to magical rituals?

Prof Judith Noble: Well, that varies from film to film. Currently, I’ve been writing about “Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome.” This film is purposefully constructed as a kind of orgiastic ritual. By the end, the god Pan is sacrificed, overtaken, and consumed by the other characters. The film’s inspiration came from a party held by fellow artists and occultists in Los Angeles in 1953, titled “Come as Your Own Madness.” It was hosted by Renate Druks and attended by several individuals, including the writer Anaïs Nin, filmmaker Curtis Harrington, and occultist Marjorie Cameron. All attendees assumed roles as deities or spirits. Anger modelled the film after this party. He had them reenact their roles, but he recreated it as a ritual in which various deities are summoned by a male Magus, portrayed by Samson de Brier, and a Scarlet Woman, enacted by Marjorie Cameron. They call forth different magical personages, deities, and entities, who then engage in the ritual. This culminates in the consumption of an entheogenic brew, which Anger has variously described in program notes as wormwood, mescaline, and so on. Pan is then consumed by the deities, who are all, I believe, returned to the inner realms by the Magus and the Scarlet Woman.

That is a film ritual made in 1954, but he re-edited it in the 1960s to heighten its entheogenic aspects, which resonated well with the counterculture of the time. That’s when it gained recognition. “Scorpio Rising” is described as a ritual dialogue between Eros and Thanatos. It’s very much a leather-biker movie. “Invocation of my Demon Brother,” if you’re familiar with Crowley’s magical system, depicts the invocation of the Holy Guardian Angel. This film ritually moves around the centre of the Tree of Life on the Kabbalah, primarily between Gevurah and Tif’eret. It’s also his ritual protest against the Vietnam War, made in 1969. It channels the energy of Gevurah, magically, to denounce the Vietnam War.

“Lucifer Rising,” the last film, stands apart. It’s an invocation of Lucifer. Anger saw Lucifer as his patron deity, referring to him as the “Lightbringer” and “the light behind the lens,” making him an apt deity for a filmmaker. So, this film serves as an invocation of Lucifer. I once had the opportunity to showcase “Invocation of my Demon Brother” and “Lucifer Rising” to an audience of occultists. This was in Bath, England, at an event organized by a wonderful occult society named Umphalos. They graciously became my guinea pigs. My goal was to test Anger’s assertion that these films function as rituals. I asked the occultists to consider this and share their feelings post-viewing. Their feedback was enlightening.

For “Invocation of my Demon Brother,” the audience understood its aggressive nature, centred around Gevurah. Many felt the film was pushing them from their consciousness to an entirely different realm. On the other hand, “Lucifer Rising” was perceived as more stately and meditative, conveying Anger’s conception of Lucifer to the audience. Showing these films to a purely occultist audience provided invaluable insights into studying his works. It’s a different experience compared to showing it at a local art house cinema to an audience not deeply involved with the occult. Does that make sense to you? Dr Angela Puca: Yes, absolutely. So, when we discuss a film being a magic ritual, does it imply that the ritual is intended to influence the audience, or is it merely a recording of him executing a magic ritual?

Prof Judith Noble: It’s designed to work on the people watching it. There are only a few sequences in Anger’s films where he’s actually seen performing rituals. It’s vital to understand that capturing the footage is just the first step in a lengthy process for him. Editing, assembling, and, in the analog era, printing the work are crucial stages. For instance, “Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome” was filmed in three days at Samson de Brier’s house in Hollywood. However, the editing and printing spanned over three months, possibly longer. Then, he re-edited and reprinted the film in the 1960s, resulting in significant changes.

Take “Invocation of my Demon Brother” as another example. This shorter film incorporates footage of Anger performing one of Crowley’s rituals, “Liber Oz,” in San Francisco in 1967. Here, the ritualist aims to free themselves from the old slave gods. Yet, he only uses snippets of that ritual, refilms it at a different speed, and then integrates it with other material. Hence, we aren’t merely observing Kenneth Anger performing a ritual. Elements of his ritual are incorporated into the film, but the rhythm and narrative are entirely governed by the editing process.

So, we’re discussing a ritual specially designed as a film, something that can only exist in film format. He’s emulating the approach of Maya Deren, who predated him by nearly a decade. While not all of Deren’s films are as ritualistic as Anger’s, she was producing films that embodied a magic unique to the screen. We’re definitely not viewing a mere recording. We’re observing something meticulously crafted to influence us magically.

I should note that in the counter-cultural 1960s, when “Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome” was screened in 1966 and 1967 (in a version he’d re-edited and retitled “Lord Shiva’s Dream” — hinting at LSD), Anger sometimes advised audiences on when to take acid to maximize the film’s entheogenic ritual benefits. So, that aspect also played a role in his work.

Dr Angela Puca: In terms of utilizing magic through art, in his case, how would he accomplish that esoterically? How would he transform a movie into a ritual meant to influence people? Was there something specific he was doing as a filmmaker to infuse those movies with magical power?

Prof Judith Noble: We’ll never truly understand the ritualistic context behind the film-making since Anger never divulged those details. We aren’t aware if a specific deity was invoked in a circle prior to the film’s creation or the exact events that transpired. Such details remain private, and I believe he chose to keep it that way.

However, what is evident from his works are the meticulous details I mentioned earlier. For instance, consider “Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome.” The three-day shoot took place in a Hollywood home he selected specifically for its decor and the occult objects it housed. He then methodically positioned every object and coloured every element he wanted in that room. Nothing was placed haphazardly; each item was intentionally positioned for a magical reason. This level of detail is consistent across all his films.

They aren’t typical narrative films, but they incorporate ritual elements familiar to magicians. In “Invocation of My Demon Brother,” filmed partly in London and the West Coast, we see fleeting clips from The Rolling Stones’ memorial concert for Brian Jones in 1969. These scenes are juxtaposed with sigils, visuals of Anger setting a mummified cat ablaze, and Bobby BeauSoleil’s band “Magic Powerhouse of Oz” descending a staircase. Each image is layered with meaning, and all are meticulously crafted to convey a magical essence. Anger’s profound knowledge of ritual magic is evident in how he weaves these elements together. While we might not be privy to the specific rituals or ceremonies that influenced the consciousness of those involved in the film, I respect that. Such details can be deeply personal.

Dr Angela Puca: In terms of the esoteric traditions he adhered to, would he classify himself as a Thelemite? Which esoteric traditions influenced his magical practices?

Prof Judith Noble: Yes, he identified as a Thelemite. Although, in his early days, he didn’t explicitly associate himself with the OTO (Ordo Templi Orientis). I’m not a member of the OTO, so others more involved might be able to speak more about this. However, in his later years, he seemed to have a comfortable relationship with the OTO. In his younger days, he sometimes denied any association, but that could just be his contrary nature. By the time he was around 20, his works were deeply rooted in the Thelemic tradition and Crowley’s magic. He frequently quoted Crowley in interviews, showcasing his deep understanding and knowledge.

In 1956, if I recall correctly, he collaborated with Albert Kinsey, renowned for the Kinsey Report on human sexuality. Together, they visited the Abbey of Thelema in Cefalù, Sicily. While the film from this visit doesn’t survive, there are photographs. One particularly famous image shows Anger and Kinsey in the dark, illuminating Crowley’s paintings in Thelma with a torch.

Crowley was a significant influence on Anger. In the late 1960s and 1970s, he conducted several interviews, particularly in England with Tony Rayns, where he delved into his magical practices. Even though his audience wasn’t always familiar with the concepts, he detailed his practices, often referencing their roots in Crowley’s work. For instance, he would explain the significance of a red jewel in an image by referring to a line from Crowley’s Hymn to Pan.

In his high school days, Anger was close friends with filmmaker Curtis Harrington, known for “Night Tide” starring Dennis Hopper and his collaborations with Marjorie Cameron. Both were familiar with Crowley from a young age. Harrington has given interviews detailing their shared interest, but the exact origin of their fascination remains a mystery. There was a Church of Thelema in Hollywood and later in Pasadena, dating back to the 1930s. Anger’s connection with Marjorie Cameron came after her marriage to Jack Parsons. He didn’t meet Parsons. He knew Cameron after that. So, there’s absolutely no evidence that he ever met Parsons.

But it is very much Crowley if there’s time and space for an anecdote. One of the things that I enjoyed very much was a great account of him taking the “Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome” to London, and it was screened in the old Institute of Contemporary Arts in Dover Street on the 1st of February 1955. There were various friends and former associates of Crowley’s present. Kenneth and Stephi Grant were there, and it’s recorded in their diaries. One of the people there was Lady Frieda Harris, who, of course, created the images for the Thoth Tarot. And she really hated the film, and she told him so in no uncertain terms. He was very young and all always quite kind of you know when when you met him he was very charming but kind of quite camp as a way of dealing with things and and when she started tearing him off a strip he said he started saying, “oh but my dear,” and she just got really angry and said don’t you call me my dear you know this is a woman who had been involved in Sufferagette direct action in her youth so the idea of a film as a magical ritual certainly didn’t go down well with her in 1955 which is a shame he does incidentally in that film there are a number of really overt visual references to the Thoth Tarot there are you probably recognize a number of times we see in the film an image that’s taken straight from poses of the what would you call them the characters they or the images in the Thoth Tarot particularly the Emperor the High Priest and the Priestess cards so there’s a there’s an extensive use of the Thoth Tarot going on in that film but Lady Frieda Harris didn’t enjoy it one bit.

Dr Angela Puca: Why do you think that Kenneth Anger is so popular among practitioners, especially in the US?

Prof Judith Noble: Magical practitioners or filmmakers?

Dr Angela Puca: Magical practitioners, as far as I know, probably even filmmakers.

Prof Judith Noble: Well, I’d say my own subjective response to that is that the films work as magic rituals. They’re wonderful experiences, so I would think that that’s the absolute core reason you know you can watch “Lucifer Rising,” “Invocation of My Demon Brother,” “Scorpio Rising,” etc., and they are a powerful form of magic which you can join in with by watching and then you can also since the digital age began you are able to watch them in the comfort of your own home. And if you want to, like I did when I first started doing in-depth research into how his films worked, or now some 15 years ago, you can watch them very slowly and take them apart from by frame and really understand all the Magical elements that have gone into them.

So I think they’re an absolutely multi-layered in-depth magical experience if you want them to be, and in, as I said, in filmmaking terms, they’re actually really skilled and beautiful things, so you know there’s a whole world of people involved in the Arts in film who were not particularly interested in the magic but just think that they’re really beautiful films. So, I think if you’re a magical practitioner, you can appreciate the magical elements and the beauty of what you’re being presented with. I think that accounts for a lot of their popularity, and the other thing is that he is so immersed in popular culture.

Although you know now that that’s becoming a little historical, there’s immense pleasure in watching, say in watching “Scorpio Rising” where he’s cutting quite S&M biker images and images of dirt track racing and what have you to every kind of innocuous sweet innocent girl group music, and there’s one point where we see a Sunday School film of Christ’s Crucifixion intercut with a biker initiation ritual, and the soundtrack is “He’s a Rebel,” and it’s hard explaining words, but when you watch it, you know it’s quite delicious it’s funny, but it also sends a bit of a shiver down your spine as well. So he’s working with all those elements, and I think that all those things make the films really pleasurable. They are not, I think, difficult to watch, which, of course, some avant-garde film is so all those things I think make him really popular.

Well, he resisted making his films available on video, although they were pirate copies, so until DVD in the late 1990s, really you had to experience Anger’s films in the cinema with a group of other people, so they they were a collective ritual and but since then I think there is an explosion of interest in him and it’s people watching him at home on their own and as I said you know being able to relate them to their own magical practice and look at the film slowly replay them and really enjoy all the elements of them and maybe they are a great way of learning about magic too in themselves, I don’t know.

Dr Angela Puca: is there any danger in watching his films, considering that they are rituals? Is it something that you might unwillingly participate in if you’re not fully aware of what the aim of the ritual is?

Prof Judith Noble: Well, given that Art House cinema audiences have been watching them since, you know, the 1950s, I would have said probably not because I think if you’re oblivious to that element or you don’t want that element, it just goes over your head. I would be interested to know more about it – I’m too young for this. I probably saw Anger’s films for the first time at the end of the 1970s or the beginning of the 1980s, but I am interested to know what it was like for people watching them whilst taking acid in the 1960s. I think that that could be quite a tricky experience, but that’s more to do with, well, taking acid, you know, can be quite an extreme experience anyway, but I wouldn’t have thought there’s that much danger in watching them you know I was interested in the response I got from them showing to occultists which are this film is forcing me out of my consciousness you know that was something that several people said to me this film is taking me out of my consciousness, but they were quite comfortable with where they went because they were practising occultists.

So it’s a difficult question to answer I mean I think for me you know there’s an awful lot of magic in an awful lot of cinema, including mainstream Hollywood and I think there can be some very difficult and quite negative magic involved in watching some mainstream Hollywood films if you are unprepared for them and what you know what happens when you suddenly find yourself in a movie that’s depicting graphic sexual violence that you weren’t expecting and didn’t want to watch didn’t know you were going to watch, you know, the film as an art form has a way of intruding deep into layers of your mind and staying and I don’t think that’s unique to Kenneth Anger the great you know surreal research practitioner Antonin Artaud noticed that very early on in the history of commercial cinema that film had that effect on the audience of going straight through the layers of the conscious mind and tapping into to very deep layers so that that is something that film does and maybe we make a kind of bargain with the devil of cinema when we watch a film that’s what happens. I don’t know.

Dr Angela Puca: I was thinking also that, and then I will start asking questions from the audience that I was kind of surprised because Kenneth Anger is not really known or popular in Italy. I think that in Italy and other European countries, Jodorowsky is more known for making movies than our rituals, though he comes after Kenneth Anger. I think, yeah, he must because he’s still alive.

Prof Judith Noble: Yes, and they knew each other there. There’s a fantastic film of a fantastic photographic image taken in 1970 of Anger, Dennis Hopper, Donald Cammell and Jodorowsky all in a line, all kind of linked arms. So yeah, they knew each other, and there’s a degree of influence going on, you know, from Anger to Jodorowsky, I guess, but you’re right, you know he’s… I said when I talk about his work, he’s probably best known in anglophone countries, which is interesting. The films don’t rely on language at all. You know, there is no speaking anywhere in a Kenneth Anger movie; there is none, you know, there’s music, there’s no dialogue anywhere. So, but also in Scandinavia and Germany and the Netherlands and, of course, when he was a young filmmaker, his work was well known in France before anywhere else and continues to be so so but as far as I’m aware, it’s an interesting thing that in Italy and Spain and Greece and maybe other Southern, you know, Mediterranean Southern European countries. No, it’s not so well known and maybe not so well appreciated. I don’t know; do you have any thoughts about why that might be?

Dr Angela Puca: I, yeah, I was surprised because, well, I didn’t know of him myself, so I’m a good representative of Italians, but I was also asking Pagan friends and esoteric practitioners that I know in Italy, and none of them knew Kenneth Anger so and when I explained his work they were comparing him to Jodorowsky.

Prof Judith Noble: Interesting, yes.

Dr Angela Puca: because that’s probably the most similar thing that you can associate his work with, although in Italy, we also have a songwriter who recently passed who has also made short movies that were meant to be rituals, although in his case, his name was Franco Battiato.

Prof Judith Noble: Yes.

Dr Angela Puca: Oh, you know him. I was thinking probably nobody knew about him.

Prof Judith Noble: I know of him, but I wouldn’t say I know the work very well. I’m just wondering, as we’re talking, is that Jodorowsky… Anger comes out of experimental, non-narrative filmmaking in the underground film, which is a phenomenon that takes place in the US.

Dr Angela Puca: By the way, João, who’s Portuguese, is saying that same thing, so that might….

Prof Judith Noble: Jodorowsky comes from somewhere different, which is the kind of narrative Art House Cinema, you know, in the tradition of, say, for example, Bunwell where the film is longer and it has a narrative, and I’m also thinking of initially very much Pasolini you know and yes his films are rituals, but they’re more in terms of film making they’re much more in that tradition of the Art House feature film where there’s more of a narrative thread and the films are much longer whereas Anger isn’t coming from there at all, you know, he’s coming from fairly and squarely from experimental cinema that begins really in the US with Maya Deren, and then you have Stan Brakhage and all the, you know the, the filmmakers who were active in the early 60s so I’m wondering if that’s probably one of the reasons and that kind of experimental cinema didn’t become a feature so much in southern European countries.

Dr Angela Puca: It could be.

Prof Judith Noble: Yeah, I don’t know, it’s interesting.

Dr Angela Puca: It could also be, yeah, it could also be that even though the other movies don’t really present the language, if his work had been distributed more in English-speaking countries, maybe, you know, the word never reached the southern European countries, but it was I was kind of surprised myself because Kenneth Anger is you know once I got to know his work it obviously fascinated me as well and I was really surprised that I had never heard of him before I mean yeah before moving to the UK and getting into in contact with other people outside of Italy.

Prof Judith Noble: And he did make a really beautiful film in Italy. It’s not talked about so much. It’s very short and called “Eaux d’artifice.” It’s shot entirely in the Water Gardens at the Villa d’Este in Tivoli.

Dr Angela Puca: I’ve been there.

Dr Angela Puca: I’ve been there on a school trip, okay, early teens.

Prof Judith Noble: Oh well, I went there on a Kenneth Anger pilgrimage, so I wanted to see where the film was made, and it’s a very beautiful film. So he made this film in Italy. It’s very short; it’s only a five-six minute film but…

Dr Angela Puca: They didn’t tell us that during the school trip.

Prof Judith Noble: No, I don’t think they would, but it’s a beautiful film and kind of shot printed with a blue filter and just about the play of light and water gorgeous thing.

Dr Angela Puca: Yeah, I definitely have to catch up on all of the movies.

Let me move on to some questions from the audience. So we have Drascus Mike who is asking, without a large knowledge about his practice. Did he have a specific outlook or theory on the impact of film on his audience? What was he trying to achieve?

Prof Judith Noble: Okay, so we’re talking about someone doing work over a period of some 35 years, and I think, for anyone doing that, what you’re trying to achieve evolves over time. Most filmmakers, especially when they’re young, just start with a passion to make films, which is certainly what what you see in “Fireworks,” which is Anger’s first film. And I think I’d refer you to… he wrote this wonderful magical biography – list of attributes for himself which he used in late 1960 in various places including the Edinburgh Film Festival where he described himself as a fanatical left-handed craftsman whose weapon was the kinematograph, whose deity was Lucifer, and there various other little aspects of that it was very much in the Crowley tradition. And I would say he’s thinking of himself as a filmmaker and a magician, and you can’t divide the two things in terms of the impact on his audience.

What he wants, I would have said, is for the audience to immerse themselves in the film and share the experience that he had in making it, in putting it together. I think it’s hard to reduce any filmmaker who makes the film as a serious art form, you know, reduce their intentions to one thing he’s in, oh let me see, in “Invocation of my Demon Brother”, he’s using subliminal images at points I mean that’s a really interesting film if you haven’t seen it go watch it it’s not a comfortable watch unlike say “Lucifer Rising” which is much slower and quite lyrical it’s not a comfortable watch and subliminal images was something that people got very worried about in the late 1960s because if you… sorry if this is getting technical here, but if you’re making a film, what you’re normally doing is shooting film at 24 frames per second. So, 24 little pictures go through your camera, and they make up one second of film. And if you have an image that lasts for three frames or less, it will imprint itself on the viewer’s mind, but they will probably not consciously remember it. Some people can remember they’ve seen something that appears for three frames. With others, it’s four, and he was using three-frame images in “Invocation of My Demon Brother.”

So, explicitly, by using that, he is doing something with your consciousness because you probably consciously can’t say what you can’t say. Oh yes, I’ve just seen that the image concerned with “Invocation of My Demon Brother” is three three-frame little blips of American GIs getting out of a helicopter in Vietnam. There’s one place in a couple of places in the film where he uses a slightly longer clip of the image so that you are aware that you’ve seen it, but throughout the film, he’s using those three frame Clips so he’s very definitely wanting to have an effect on the audience that is you know use going straight to the subconscious and the use of incidentally the use of subliminal images was banned very quickly because it was in cinemas were that was being used in adverts so in commercial cinema and specifically in advertising it was banned very soon after people became aware of what it was but you know he will use techniques like that for his magical purposes does that make sense to you Mike.

Dr Angela Puca: Yes, well, Mike tell us in the chat. The next question: I think it does make sense. The next question is from Night Gaunt, and he says do you know if he haded sigils in some of his films and utilized them being viewed by others as a means of Chaos Magick.

Prof Judith Noble: He uses sigils. He uses them in “Invocation of My Demon Brother” and particularly in “Lucifer Rising,” but “Lucifer Rising” was made over a long period. He started making it in the mid-60s and didn’t come up with the version that he wanted to show until 1981, so that sort of predates Chaos Magick. Really, he’s using sigilisation, but in a pre-Chaos Magick kind of way; you can read it now if you’re a Chaos practitioner and critique it from a Chaos perspective. I think he uses the unicursal hexagram in “Lucifer Rising” and uses a couple of other sigils, but he’s not consciously part of the Chaos Tradition at all because the film is made before it happens.

Dr Angela Puca: Thank you, and we have another similar question from Latif, who asks, do you think Anger was a successor of Austin Osman Spare in terms of the magic being in the art? Was Anger influenced by Spare?

Prof Judith Noble: Hello, Latif. I recognize you. I think he was a successor of Spare in general terms of ‘the magic is the film.’ The film is the magic definitely, in that sense, whether he was directly influenced, I don’t know. He spent quite large chunks of his life in the UK in London a large part of the time between 1966 and 1970 he was in London. He was very influential on the Rolling Stones for a time. He was introduced to them by Anita Pallenberg, and so he may well have looked at Spare’s work during that time. I can’t find any recorded evidence of him talking about it or mentioning it. So I just don’t know. I know that Michael Staley, who is working on Kenneth and Stephy Grant’s Diaries, very kindly shared information from those diaries with me. So Anger was very interested in what Kenneth Grant was doing for a while in 1955 and 56. They kept up a correspondence, and the Grants were very interested in him and also very much in Margerie Cameron, but I don’t have any concrete evidence that he actually looked at Spare’s work, but it would have been perfectly possible given the circles he was moving in London in that period from to do so and of course, you know, he visited London many times in subsequent years.

I remember seeing him at an exhibition of Crowley’s paintings at the beginning of this century. So again, you know it would have been perfectly possible for him to see Spare’s work, but of course, the films that we’re talking about, the last one was made in 1981, so I don’t know. I’m sure he saw Spare’s work later in life, but I can’t find any, you know, we’ll never know, I don’t think, but it’s a great, it’s a great thought. One thing I did work out was that he and Jean-Luc Godard, the great French filmmaker, were on set in the same room at the same time with the Rolling Stones when Godard was filming what became One Plus One Sympathy for the Devil, and there’s a combination you know Godard in many ways was the absolute polar opposite of Anger although Godard did come up with a great line I don’t know if I’m sure he didn’t mean it in an occult sense but he did say film is magic at 24 frames a second.

Dr Angela Puca: So then we have another question, which is a bit cheeky.

Dr Angela Puca: Artists are known to be very eccentric and to play with their audience. Is there any way to demarcate the practitioner from the artist who is possibly posing as a practitioner?

Prof Judith Noble: Well, Kenneth Anger was completely eccentric and played with his audience all the time, and he played with his interviewers. He told outrageous stories and was quite happy for people to believe them. One of the great things he did in 1967 was that he announced his death in various newspapers in New York. And what he was doing was evolving from one magical stage to another, but most of the avant-guarde filmmakers who knew him, people like Jonas Mekas P Adam Sydney Stan Brakhage, actually thought he died for a couple of days. And he was absolutely able to play with the audience, although I’d make a distinction, you see, because I’ve seen Kenneth Anger playing with the audience in a live event when he’s talking to them. I don’t think the films play with the audience in quite the same way, but the films are so multi-layered that, you know, there are layers of humour in there. So you know, in “Invocation of My Demon Brother,” he’ll intercut these really fragmentary shots of him doing Crowley’s Liber Oz ritual with Bobby BeauSoleil’s band, Magic Powerhouse of Oz, and he wants you to play with that idea he wants you to think about Dorothy and The Wizard of Oz and Crowley’s Liber Oz in the same, in the same frame. He plays with all that, absolutely. Is that some kind of an answer, I hope, for Latif, but he was a very trixy character, you know.

Dr Angela Puca: And what about the similarities between The Wizard of Oz and Liber Oz?

Prof Judith Noble: Yeah, absolutely. What about them? You see, for him, you know, there was that spectrum that had popular culture and deep magic in it. And they were, for him, part of the same spectrum absolutely. So the playful and the camp was just as important in lots of ways, you know, as the really deep ritual aspects of “Lucifer Rising,” which is a very beautiful and very lyrical film. But you know, it still has those odd touches of humour and popular culture in it, but every single thing in these films has layers of meaning, so watching again, watching ‘Lucifer Rising” frame by frame, there’s a little bit where you see Anger treading around a magic circle, very deliberately and then there are flash cuts of an image of a tiger. And there’s a little phrase in Crowley, which I’m indebted to my friend Julian Bain for locating, where Crowley says something like the tread of the magician around the circle should be purposeful, exactly like the tiger stalking its prey. So, you know, be that tiny little image of a tiger that’s there just for a second or so, but it’s got those layers of those layers of meaning behind it.

Dr Angela Puca: Yeah, that’s very interesting, and then patchcrist is asking, what was the film Kenneth made in Italy?

Prof Judith Noble: It’s called “Eaux d’Artifice” E A U X Waters plural in French d’Artifice. He mistakenly thought that Eaux d’Artifice in French meant waterworks, and he was obsessed with the idea that the Cardinal d’Este, who built the Water Gardens, actively was into water sports and therefore the, you know, Water Gardens there had had this kind of pornographic edge to them. Eaux d’Artifice doesn’t mean I don’t think it makes much sense in French, but you know his previous film had been called “Fireworks,” so he thought he was making a film with a French title of Waterworks and he shot it in Italy in 1953 maybe we can put that in the chat or something at the end so you can look for it if you get I mean I’m very oldfashioned so still sometimes use DVDs to watch Anger’s films because can watch them frame by frame if I want to if you get the British Film Institute’s compilation DVD of Anger which is actually really really good if you still got the means to play it that has “Eaux d’Artifice” and all the short films on it.

Dr Angela Puca: And how, otherwise, how can people watch Kenneth Anger’s films?

Prof Judith Noble: Well, I still tend to watch the DVDs. You can download them from various download sites, and you can watch them on YouTube. The quality of the versions on YouTube is variable, you know, because fans put them there and what have you, but towards the end of his life, he was represented by a gallery called Sprüth Magers and Sprüth Magers have – you can find your way into the downloads via them. I think they’re very good. Some of them in some of them will be on the British Film Institute’s I player actually I know it’s slightly old-fashioned these days, but I really do recommend that DVD because the quality is just really really good and for someone who’s working with something where you know the technical qualities what he’s doing are so import it’s actually really good to be able to watch them I would still say if they’re if you see them being screened at your local Art House Cinema or Film Festival that’s kind of the best way on the big screen. I mean, you’re always going to see a digital version these days, not celluloid print, but that’s fine that J Paul Getty Jr was an admirer of Anger’s work and paid for really good digitally restored versions of all the films which are what we watch now so if you get that DVD or you get downloads from Sprüth Magers they’re going to be that quality, but if you watch them try to watch them in a really good-quality way because they are so beautiful you know sometimes watching a version that somebody’s put on YouTube can be a little bit like watching a photocopy I think.

Dr Angela Puca: We have somebody else from the audience asking whether you’re familiar with the “Cremaster Cycle” by Matthew Barney. And they say I’ve only ever seen clips, but they feel ritualistic.

Prof Judith Noble: Yeah, I am familiar with the “Cremaster Cycle.” I think it’s a really wonderful piece of work. Matthew Barney’s a really interesting filmmaker. I think they have a ritualistic element to them, but I don’t think they are intended to be full-on magical acts within a ritual magic tradition like the Thelemic tradition in the same way as Anger’s, but they’re great films, and they’re really worth seeing I would really recommend them.

Dr Angela Puca: Thank you. So I guess that we have answered a lot of questions, so we can let you go, Judith. Prof Judith Noble: Are you sure I’m happy to stay as long as you want me, having been, you know, missing in action at the beginning, for which I can only apologise? I live in a very rural area, and this hasn’t happened for a long time, and it would just happen today, and I’m really sorry.

Dr Angela Puca: It’s fine. Apologies accepted. I’m sure that everybody forgives you.

Prof Judith Noble: Thank you, everyone, for sticking with it.

Dr Angela Puca: Yes, thank you to everybody who remained here connected.

Prof Judith Noble: Yeah, thank you. It’s very above and beyond, really.

Dr Angela Puca: Okay, and thank you again, Judith, it was lovely chatting with you.

Prof Judith Noble: And you, Angela, it’s great, thank you, okay.

Dr Angela Puca: So let’s close now. So, thank you all so much for sticking around for the whole interview, and I hope you enjoyed it. Let me know in the comments what you thought about it, especially if you’re watching this afterwards, and if you like this interview, don’t forget to smash the like button and subscribe to the channel if you haven’t already. Activate the notification bell because that way, you will always be notified when I upload a new video and share this interview and all of my videos around so that the Symposium can grow. So thank you all so much for being here, and stay tuned for all the academic fun.

Bye for now.

Judith Noble is Professor of Film and the Occult at Arts University Plymouth (UK). She began her career as an artist filmmaker, exhibiting work internationally and worked for over twenty years as a production executive in the film industry, working with directors including Peter Greenaway and Amma Asante. Her current research centres on artists’ moving image, Surrealism, the occult and work by women artists, and she has published on filmmakers including Maya Deren, Derek Jarman and Kenneth Anger. Her most recent publication (as editor) is The Dance of Moon and Sun – Ithell Colquhoun, British Women and Surrealism (2023, Fulgur). She continues to practice as an artist and filmmaker; her most recent film is Fire Spells (2022), a collaboration with director Tom Chick. Her recent work can be found at www.iseu.space. Her film work is distributed by Cinenova.